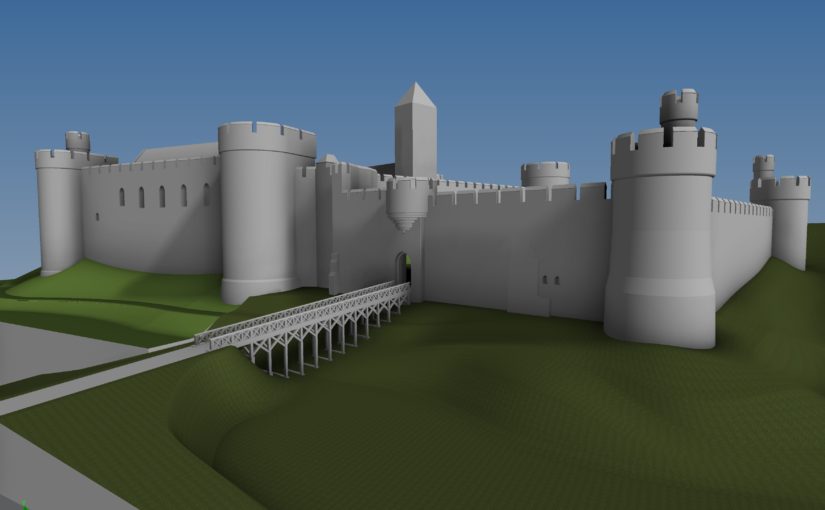

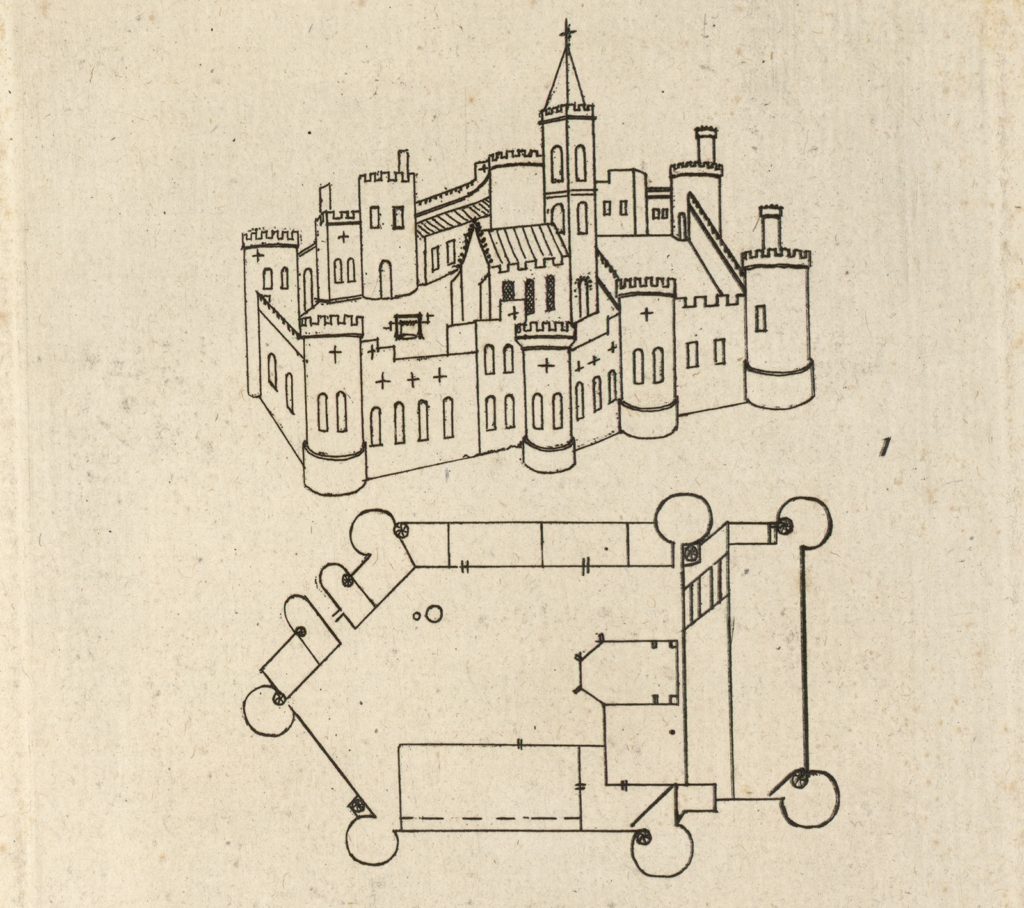

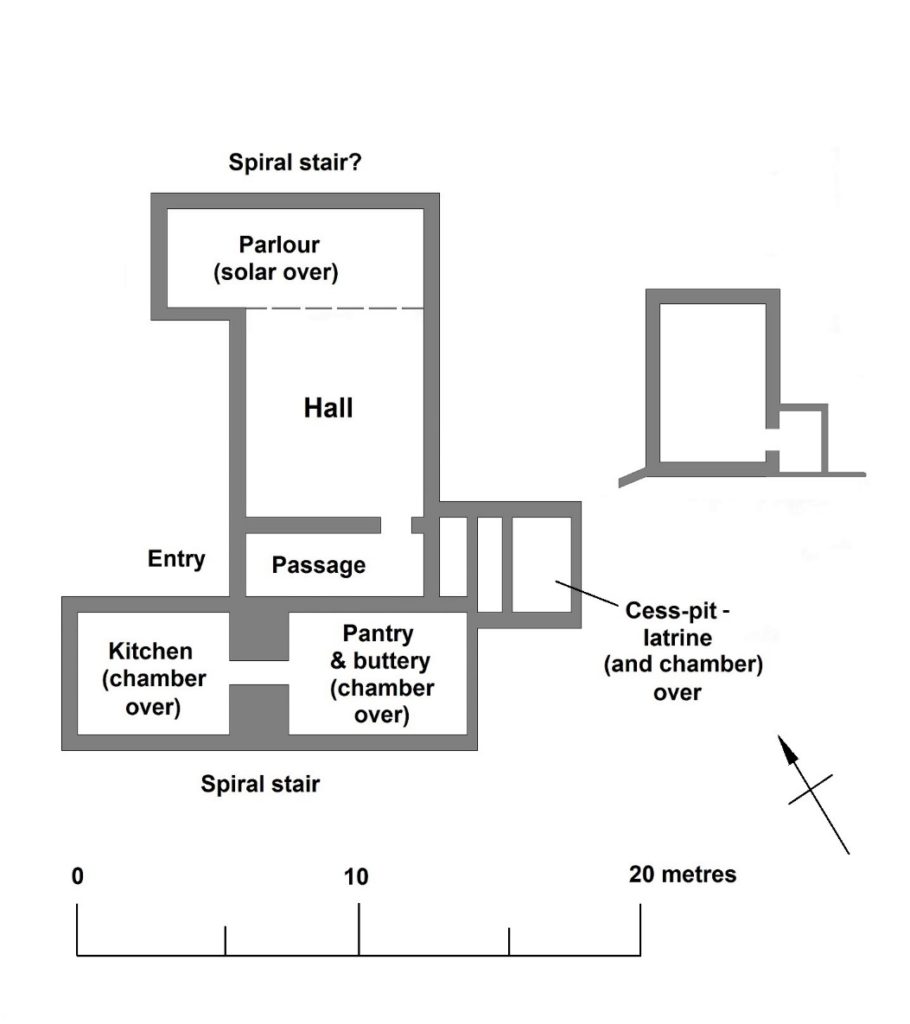

In rural Lincolnshire, nearly 30 miles east of Lincoln, stand the remains of a castle once held by royalty. The remaining walls and towers of Bolingbroke Castle are still 3m tall in some parts, and you can make out its distinctive hexagonal shape. The buildings that once crowded together inside the castle have long-since disappeared.

Bolingbroke Castle was founded in the 1220s by Ranulf de Blundeville, Earl of Chester and Lincoln and through marriage it ended up in the ownership of the House of Lancaster. John of Gaunt, Duke of Lancaster, lived here in the 1360s and the castle gave its name to his son Henry Bolingbroke, later crowned King Henry IV, who was born here in 1367. The history of the site is reasonably well documented, especially compared to castles not owned by the Crown, but there remain unanswered questions about its origins and development.

In 2018 we gave Heritage Lincolnshire a grant to delve deeper. They would carry out a geophysical survey to establish if there are buried remains immediately south of the castle and on Dewy Hill, which might be the site of an earlier castle, built before the stone one still visible at Bolingbroke.

The plan was to use ‘magnetometry’. It works by measuring how magnetic the soil is and then plotting the results on a map. It allows you cover a large area quickly, and over the course of two days the Heritage Lincolnshire team surveyed more than five hectares (about five times the size of Trafalgar Square).

There is some natural variation in the soil, but typically human activity such as cooking hearths or stone walls have a different magnetic signature to the soil around them as they are made from different materials. Magnetometry can also be used to find filled-in ditches as the fill might contain traces of human occupation.

The first stage was to survey Dewy Hill, sitting 400m north-west of Bolingbroke Castle. It was excavated in the 1960s, and a digital survey of the terrain suggests a rectangular feature still survives. We hoped the geophysical survey would show how extensive the buried remains are, and the shape and size might give us an idea of what it is. Essentially, was it a castle or some other type of important place? There was a slight hitch…

But Heritage Lincolnshire did eventually get to take their magnetic gradiometer for a spin! Next, they surveyed the area south of the castle as it might contain an extension of the castle which has since been dismantled. Are there traces of this possible enclosure, or was there perhaps a garden here? In the later Middle Ages it was especially popular to shape the landscape around a castle. Right in the middle of this area is a rectangular piece of ground called the ‘Rout Yard’, but it’s unclear when it was created so the survey aimed to establish how this area relates to the castle.

Understanding the results takes a trained eye, and Heritage Lincolnshire have a highly skilled team of experts. They were able to find a few anomalies, but they either appear to be modern (there may be a concrete slab on Dewy Hill) or natural geological features.

The point of an exploratory project is to find out what lies beneath. Oddly, we expected something to be at Dewy Hill since earlier excavations suggested there might be some activity. The search for a possible bailey suggests that perhaps one did not exist or if it did it may have been insubstantial. That would mean the ruins we see today may represent the extent of the castle at its peak. Interestingly the fashion for having gardens might have passed Bolingbroke by. It was an important place, so may have begun to fall out of use by the time gardens became a common part of high-status medieval landscapes.

Despite the siege of 1643, the survey did not uncover ‘siegeworks’ which would have been built by the Parliamentarians. This might be because the siege was relatively short.

As a result of this work, we know more about how the surroundings of Bolingbroke Castle. Other types of geophysical survey may pick up different pieces of evidence, helping build a fuller picture of the area. Surveys like this are an important tool to understand sites, and Heritage Lincolnshire’s work will inform any future work at the castle.

Thank you to the owners, the Duchy of Lancaster, for allowing us to carry out the survey, to English Heritage who are guardians of the site, and to the volunteers from the local community who helped with the fieldwork. Projects like this really do take a village.

A full report has been prepared by Heritage Lincolnshire.

![[10] Druminnor Castle - "Woops!"](https://farm6.staticflickr.com/5125/5340893447_176baa5abf_b.jpg)