In the later Middle Ages, the Keith family were some of the most important people in Scotland. Sir Robert Keith was made marischal of Scotland in 1293, a title that descended through his heirs. As marishal, Sir Robert and his successors were could hold courts during wartime and were responsible for maintaining order within the Scottish parliament. The castle at Keith Marischal, half a day’s journey from Edinburgh, was the family’s ancestral home.

For a family which was amongst Scotland’s richest in the 16th century, their seat was an important place which would have embodied their power and prestige. The great hall, the social heart of the castle, vied with royal palaces in its size. William Keith, 7th Earl Marischal was forced to sell Keith Marishcal during the Civil Wars, and, despite being an important piece of Scottish history, the castle was gradually demolished. Part of the castle survives and was incorporated into the later house built on the site, but much of Keith Marischal has vanished.

In 2017, Miles Kerr-Peterson suggested carrying out a geophysical survey to look for buried remains just north of where the house currently stands. He successfully applied to the Castle Studies Trust for funding, and in May 2018 he and Rose Geophysical Consultants visited Keith Marischal to search for the evidence in an area of 2 hectares.

Two methods were used: resistivity and ground penetrating radar (GPR). As different materials conduct electricity differently, testing the electrical resistance of the ground can be used to find features such as walls (high resistance as there is little water) or ditches (low resistance as ditches tend to hold water), and is effective to a depth of about 0.75m. GPR works by sending electromagnetic pulses into the ground and tracking how they are reflected. Part of the area north of the house is a carpark, which makes survey resistivity ineffective, but GPR can still be used.

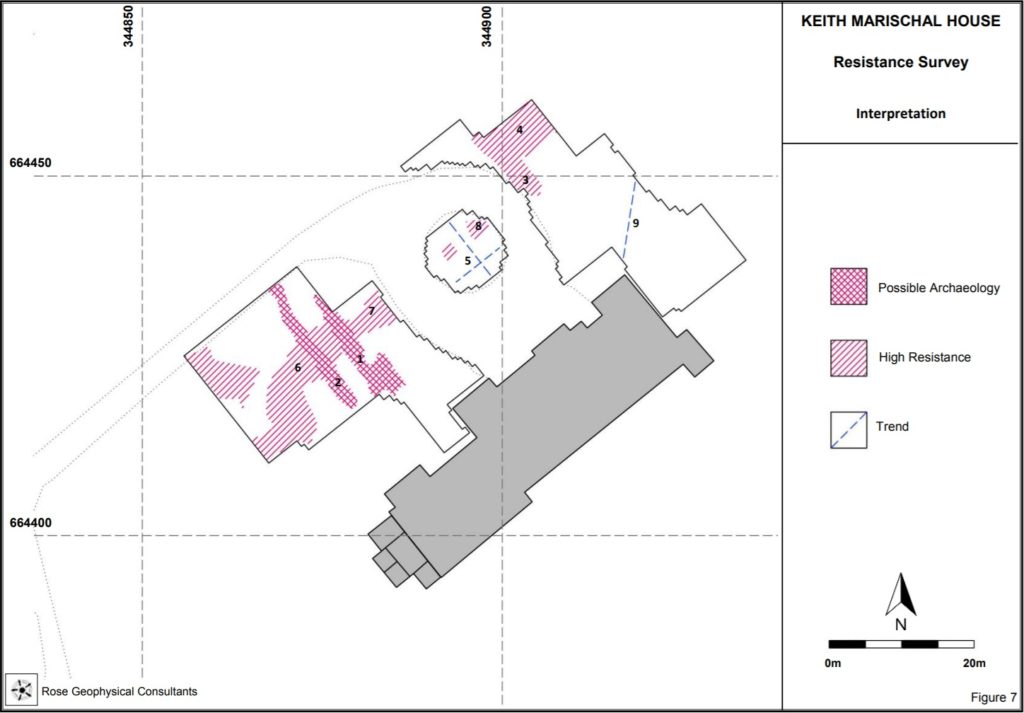

Deciphering a geophysical survey takes a trained eye. The resistivity survey found several features, and working out what they are has been an interesting challenge. There are two features running in a mostly straight line perpendicular to the current house at the west end of the survey. The longer of the pair could be a drain, but it’s uncertain. And what are the features at the north end? The feature runs beyond the edge of the survey, so we don’t know the full shape and size of it. With trees nearby it could even be part of a root system, but the straight lines suggest it could be man-made and could be part of the lost castle.

GPR allows us to peer deeper, and to work out a rough stratigraphy of features. The survey was able to corroborate some of the anomalies found with resistivity. The pair of parallel features at the west end are visible, but the one on the right runs deeper. The fact it’s so narrow suggests it might be a drain. The GPR also found an anomaly at the north end of the survey area, lining up with the one found using resistivity. It was visible some 0.38-0.63m deep, which suggests it might be artificial rather than natural.

The results of the survey are certainly interesting. We didn’t find the extent of the lost Keith Marischal Castle, but most discoveries don’t happen overnight. Geophysics is an excellent way to identify areas of interest ahead of excavation. Without excavation, we can’t be sure about the interpretation of these features. If the anomaly at the north end of the survey is part of the lost castle, we don’t have a way of dating it without breaking out a trowel.

The survey was a vital step in the understanding Keith Marischal. Thanks to Miles and Rose Geophysical Consulting, any future excavations will know where to look. Keith Marischal has an exciting future, and the Castle Studies Trust are proud to be able to have played our part in supporting the work.

Dr Miles Kerr-Peterson is an affiliate in Scottish History at the University of Glasgow. His new book, A Protestant Lord in James VI’s Scotland George Keith, Fifth Earl Marischal, touches on the Keiths and is out now.