Project lead of the Canterbury Castle Visualisation project, Dr Katie McGown, gives an update on how the project is progressing.

The Visualising Canterbury Castle project is in the process of producing a new digital reconstruction of Canterbury Castle’s Norman keep. In our last post we discussed the first of a series of co-design sessions we have organised to allow a range of expertise and stakeholders to help us develop and interrogate the model we are producing. However, this is not the only way we are collating information to inform our understanding of the built structure.

Subscribe to our quarterly newsletter

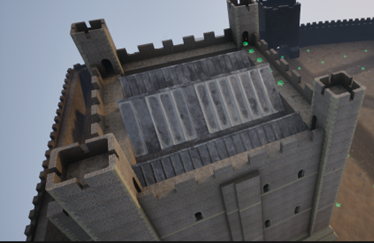

Canterbury Castle has been closed to the public since 2018, and as it is currently being refurbished, the walls are obscured by scaffolding. Because of this, initially we drew heavily on Excavations at Canterbury Castle (Bennet et al, 1982) published by CAT, which features elevation and plan drawings. This helped us map out the size and shape of the building for the early stages of the model. However, over the course of the development of the project, questions have arisen about areas of the building which are no longer extant, and we’ve had to piece together information from other sources, and crucially, by visiting other castles.

After the first co-design session our student interns, Ethan Serfontein and Joseph Seare, and Technical Lead, Mike Farrant, were invited to Rochester Castle by Dr Jeremy Ashbee, Head Properties Curator, English Heritage. Through visiting a similar structure, the team gained greater understanding of both the defining features of a Norman keep, and how we can draw evidence from the building to inform our reconstruction.

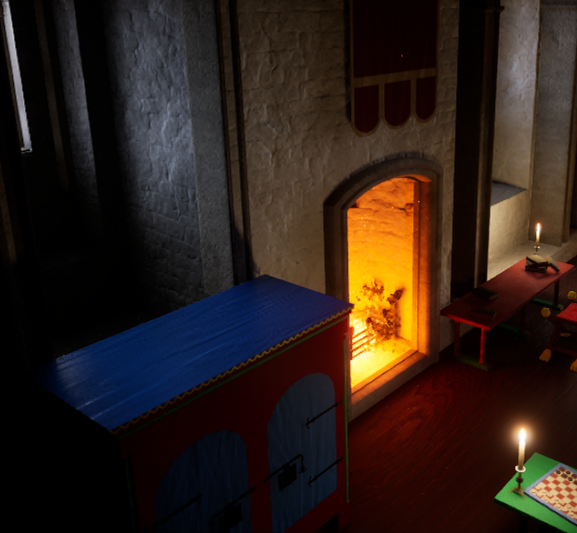

As we continued to develop the digital reconstruction, questions began to emerge about the structure of the outer staircase and how this would look. This is a difficult question to answer given that the structure no longer exists. However, the team were able to develop a better understanding of how the space might have worked by comparing their observations in Rochester with a visit to Dover Castle. Professor Alan Meades, Dr Cat Cooper, Mike, Joseph and Ethan went down to Dover and spent time discussing the differences between the three Royal Norman castles in Kent, and documenting features like the staircase. Dover Castle also gave the team the opportunity to appreciate the lovely Norman interiors.

Subscribe to our quarterly newsletter

Recently, we were able to visit Canterbury Castle, courtesy of Lian Harter from Purcell and Alison Hargreaves from Canterbury City Council. Dr Katie McGown and Cat donned high vis, hard hats, and steelies to climb the scaffolding. This visit allowed them to think about sight lines around the city, but also observe important details such as this stunning herringbone brickwork in the fireplace. The tour also gave us incredible insight into the refurbishment of the keep, and how that process might be incorporated into the eventual curriculum resource that accompanies the project.

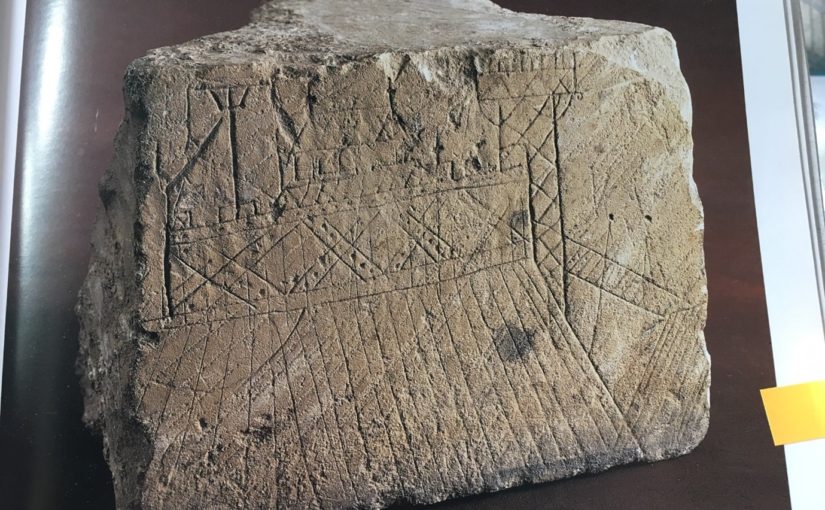

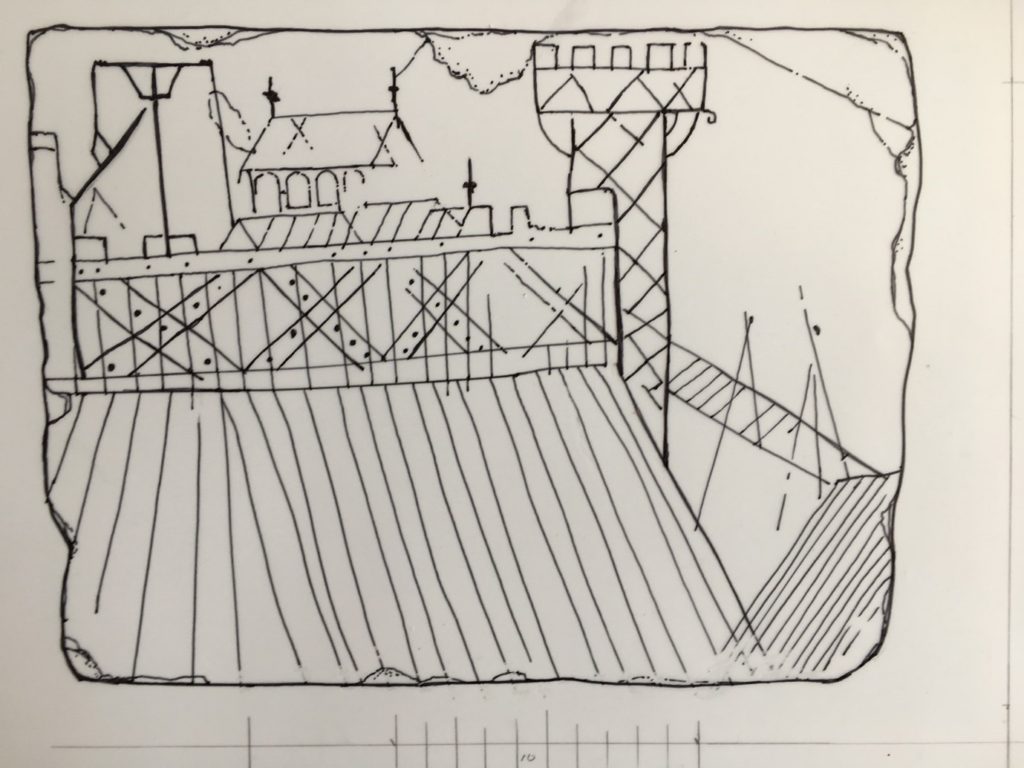

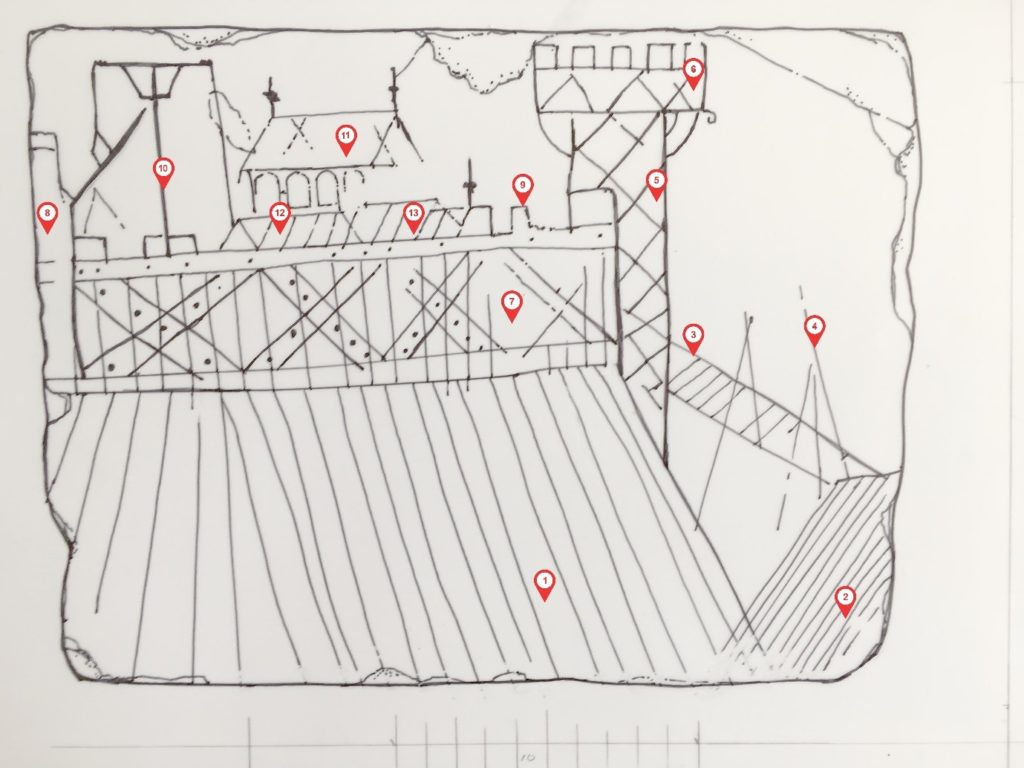

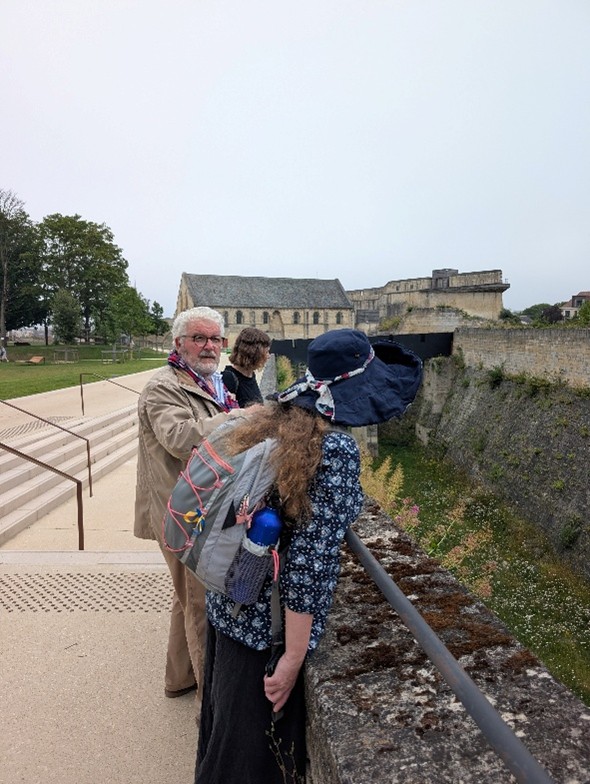

We’ve also been thinking more broadly about how the project might fit into wider activities in development for the 2027 European Year of the Normans. Professor Leonie Hicks, Cat and Katie travelled to Caen Castle to see about possible collaborations for work at the site, and were delighted to have a detailed tour led by Curator Jean-Marie Levesque around the delicate foundations of Caen Castle’s Norman keep. The team also took the opportunity to see the Bayeux Tapestry prior to its voyage to the British Museum.

Each of these visits informs the development of the digital reconstruction. For example, following the visit to Canterbury Castle, the fireplaces were adjusted to showcase the herringbone brickwork.

Similarly, being able to see the refurbishment of Canterbury’s Caen stone has informed the exterior of the digital reconstruction.

The team has one final visit planned to Norwich Castle before the end of the project, and we are looking forward to continuing to develop our understanding and appreciation of Norman keeps.