This post was written by Dr Audrey Thorstad, Lecturer in Early Modern History at Bangor University.

As castle scholars and enthusiasts, we enjoy learning about history, exploring how the remains of the past can teach us about the lives of people who came before us, and perhaps what we might learn about ourselves through their experiences. Did those in the past feel the same way? How did they view their own history? How did they embrace or even manipulate the history of the landscape in which they lived?

The physical and material remains tell us a story of a layered history. Any given castle can have centuries of history layered and intertwined with one another. For Tudor castle owners, builders, and renovators, the past played an important role in how they used and interpreted the building and the landscape.

An interesting example, though just one of many, is Cowdray House or Castle in West Sussex. The building that survives today had two main phases of construction during the late 15th and early 16th centuries. The first phase started by Sir David Owen from around 1492 and saw the completion of the eastern and northern ranges. The second phase began when Sir William Fitzwilliam, later earl of Southampton bought the estate in the late 1520s and completed the southern and western ranges. Although it appears that the surviving physical remains depict a completely new build, thirteenth-century floor tiles indicate there may have been an earlier residence on the site.

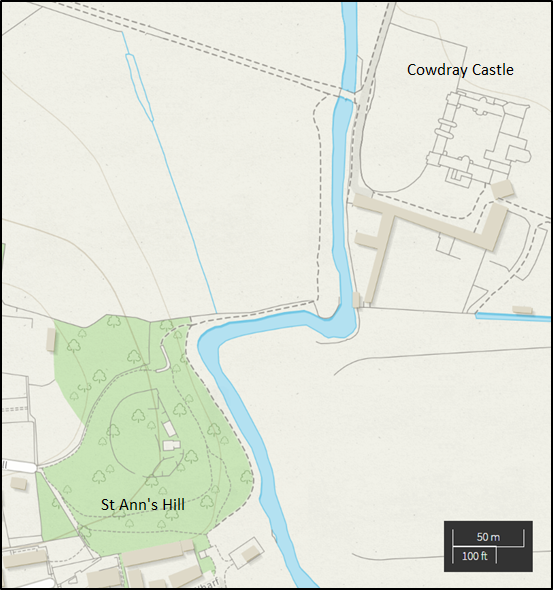

The placement and building of Cowdray was no mistake. To the west, the residence looks out onto the town of Midhurst; to the north and east the castle looks out onto parkland. Fitzwilliam received a licence to impark and crenellate in 1533 from Henry VIII. The licence allowed him to impark 600 acres of land, meadow, pasture and wood.[1] To the south of Cowdray is St Ann’s Hill, the location of a Saxon cemetery dating from the fifth and sixth centuries as well as a Norman castle owned by the Bohun family until the 15th century.[2] These views were meant for those in the castle as well as those approaching the castle. The town and parkland scenery evoked lordly privilege and status, while the closeness of the newly built Cowdray and the old Norman castle gave the observer a sense of historical significance.

By rebuilding the castle not on the original site of St Ann’s Hill, but approximately 400 meters away, the Tudor builders were using the past in very interesting ways. The new build broke away from the Norman past and the Bohun family tradition, yet kept the site as a physical memory of that history. Cowdray does not have a completely new history starting in 1492 when Owen started building the castle, but an intertwining and connected history to the town and historical sites around it.

Owen and Fitzwilliam were not alone in their endeavour to create their own legacy by shaping the past. John de Vere, thirteenth earl of Oxford renovated his familial stronghold at Hedingham Castle making the Norman great tower the central building of the inner bailey with his late-fifteenth-century brick towers surrounding the twelfth-century great tower like a monument to his ancestors. It was not just castle building that allowed the Tudor nobility and gentry to use the past. Sir Rhys ap Thomas, for example, used the coat of arms of Urien of Rheged as his own, claiming descent from the sixth-century king of Gower. The use, and arguably manipulation, of history by the sixteenth century elite was nothing new. The nobility and gentry throughout the Middle Ages were interpreting and adopting the past. What sets castles apart is the constant, and at times, unbridled incorporation of structures, materials, landscapes, and histories that came before.

[1] Letters and Papers, Foreign and Domestic, of the Reign of Henry VIII Vol. 6 p. 44 No. 105.25

[2] For more information on the castle, see Bill Woodburn and Neil Guy, ‘St Ann’s Castle’, Castle Studies Group Journal, 19 (2005-6), 28-30.