Project lead of the 2022 project Dating the Medieval Towers of Chalkida, Greece, Dr Andrew Blackler, gives an update on how work on the project has progressed.

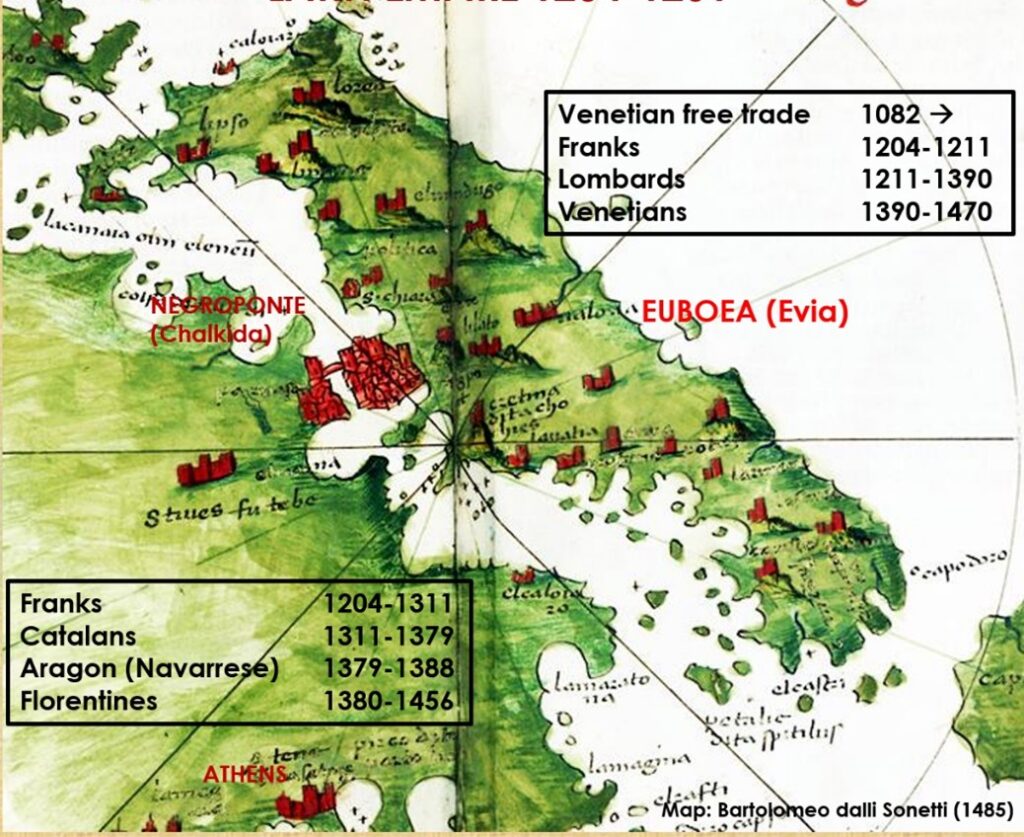

Mention the Acropolis to anyone and they will probably immediately identify it with Greece. Yet the Norman invasions of Greece just fifteen years after the battle of Hastings are almost unknown. Few will know too that the magnificent horses adorning St Mark’s Basilica in Venice were pillaged from Constantinople in 1204, and that much of Central Greece and its islands were ruled for nearly three hundred years by a succession of western adventurers from as far away as Catalan Spain, until the region’s annexation by the Ottoman empire at the end of the fifteenth century. This is simply illustrated in the figure below, based on a map of Central Greece by the Venetian cartographer Bartolomeo dalli Sonetti c.1485. at a time when Athens was just a small provincial town whilst Negroponte was a major city.

Subscribe to our quarterly newsletter

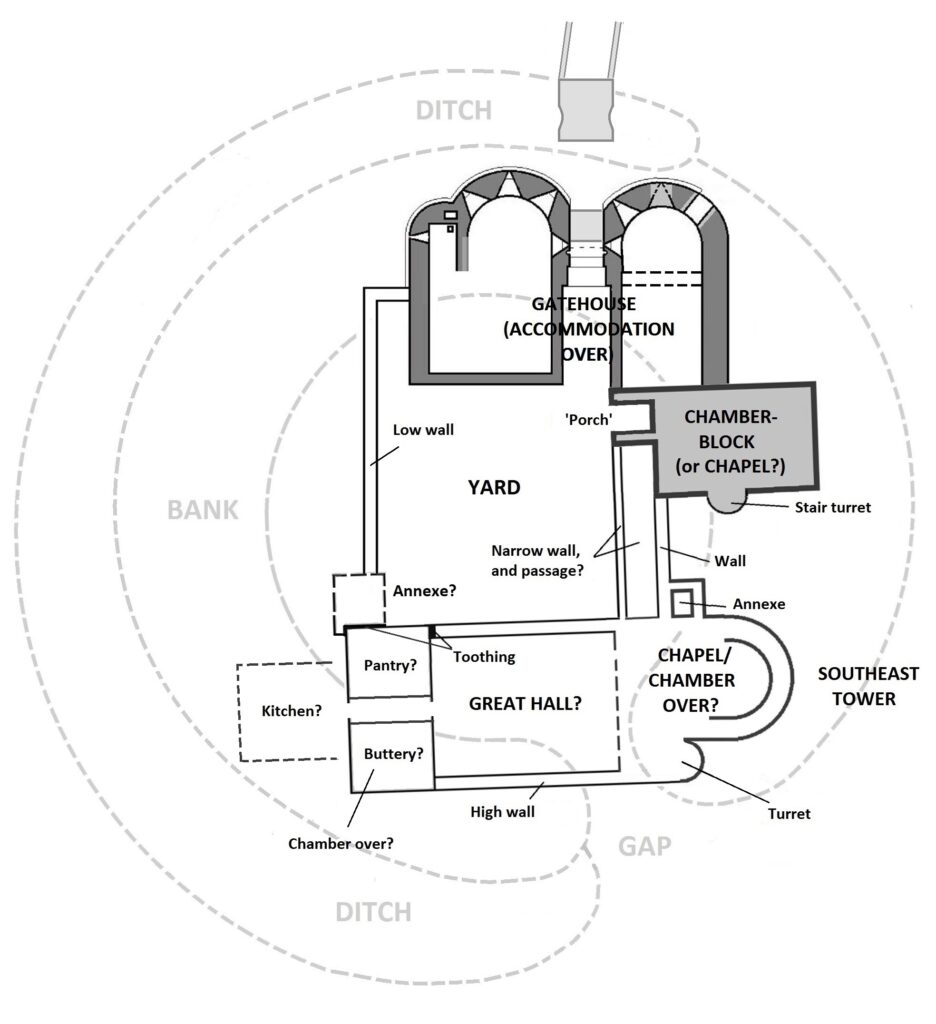

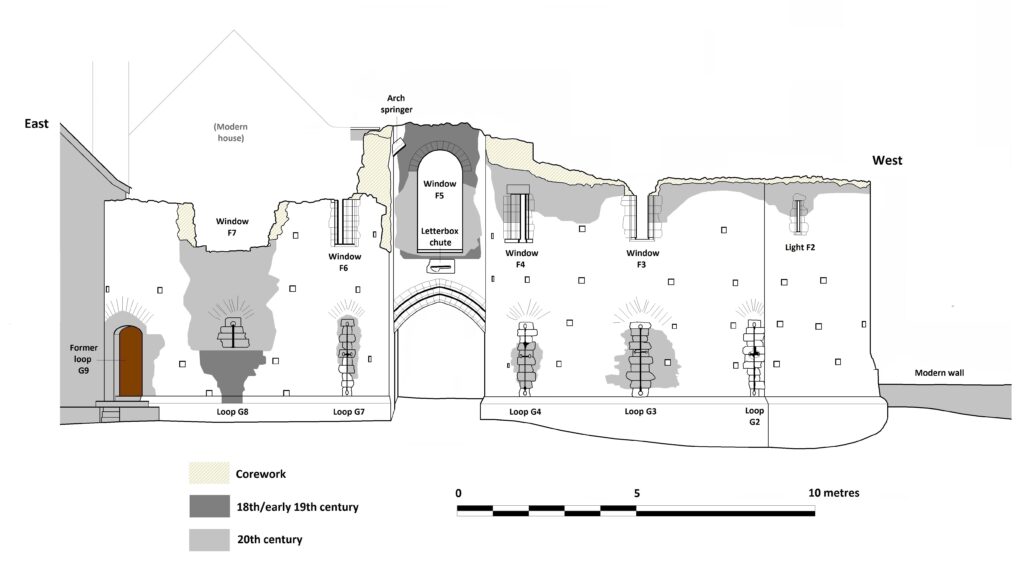

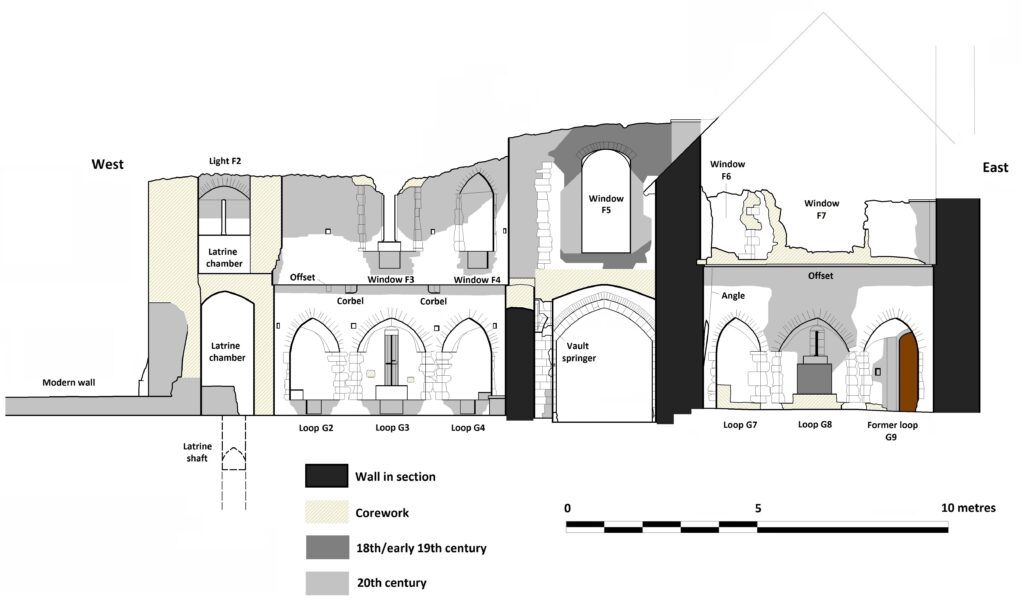

This is the background to the five-year survey of the hinterland of medieval Chalkida (Negroponte) on the island of Evia (Euboea), which I was invited to join by Professor Joanita Vroom of the University of Leiden Dr Alexandra Kostarelli of the Ephorate of Antiquities of Euboea in 2020 – the first major archaeological survey in Greece to focus exclusively on the medieval period. Initially, times were tough as the COVID shutdown and lack of funding restricted our work, but slowly our team established a track record supported by sponsorship from institutions such as the Castle Studies Trust (2022).

This project, in conjunction with the National Centre of Scientific Research laboratory at the University of Athens, undertook the radiocarbon dating of sections of wood taken from within the walls of a group of medieval towers, a ubiquitous feature of the region. It was very successful. For the first time we were able to conclusively prove that the more than one hundred towers, that once stood on the island, were not built immediately after 1204 as part of a colonial process of control and exploitation, but during the fourteenth century, probably to protect local villages against pirate attack from the sea, an endemic problem of the era.

During five years of work over the summer months our team of over thirty specialists and student volunteers has now recorded all the known medieval monuments of the region. Using intensive surface survey techniques and trial excavation trenches, evidence from ceramic, coin, glass, iron, fauna and bone finds is slowly allowing us to reconstruct a picture of the medieval life of the region. Trading links have also been identified east as far as the Black Sea and Palestine, and west to other centres around the Mediterranean. More recently, we have attracted major sponsorship and are now undertaking geophysical surveys to identify structures hidden under the earth, digital reconstruction of selected monuments and have even instituted a second phase of radiocarbon dating. In parallel, specialists have been investigating the medieval archives of the Republic of Venice and Ottoman administrative records held in Istanbul. A detailed report of the results of the first two years’ survey campaigns can be found at https://poj.peeters-leuven.be/content.php?url=article&id=3293423&journal_code=PHA&download=yes

I will leave you with a final thought: the medieval world, despite the slow pace of travel, was much more inter-connected than people generally believe. Two examples illustrate this. Many know that Harald Hardrada, king of Norway and the last great Viking, invaded England in 1066, and was killed at Stamford Bridge just weeks before the battle of Hastings. Few realise that he made his fortune fighting for over ten years in the elite Byzantine Varangian Guard, and that this had probably helped fund his claim to the Norwegian throne. Recent analysis of finds in the British Museum from Sutton Hoo also suggests that Anglo-Saxon mercenaries were even fighting alongside the Byzantine emperor Justinian in Asia Minor as early as the sixth century. This is the sort of international research that the ‘seed capital’ provided by the Castle Studies Trust has spawned over the last three years.