Bodiam Castle is well known in castle studies; whether it was a fortified structure or built to display the status of the owner. This debate has been explored elsewhere, particularly by Professor Matthew Johnson[1]. Traditionally the building has been considered from the exterior, with a few notable exceptions[2], further until recently only ground floor plans of the building have existed. As part of the Lived Experience in the Later Middle Ages project we undertook a survey of the building and created plans of each floor level and some elevation drawings[3]. To undertake the survey we used a Leica reflectorless Total Station linked to download in real time straight into AutoCAD using the software TheoLT. This allowed us to view the survey data as work progressed and to record the building in three dimensions (3D).

Having the results of the building recorded in 3D allowed us to start thinking about the space beyond the traditional drawings, we had generated and we could think about the building in a number of new ways. The 3D data was used as a basis for creating models of the building in the medieval period; rebuilding the fallen walls, reroofing the apartments, and furnishing the rooms. These models can be used to create beautiful illustrations of the spaces, but they can also be used to tell us about living in those spaces.

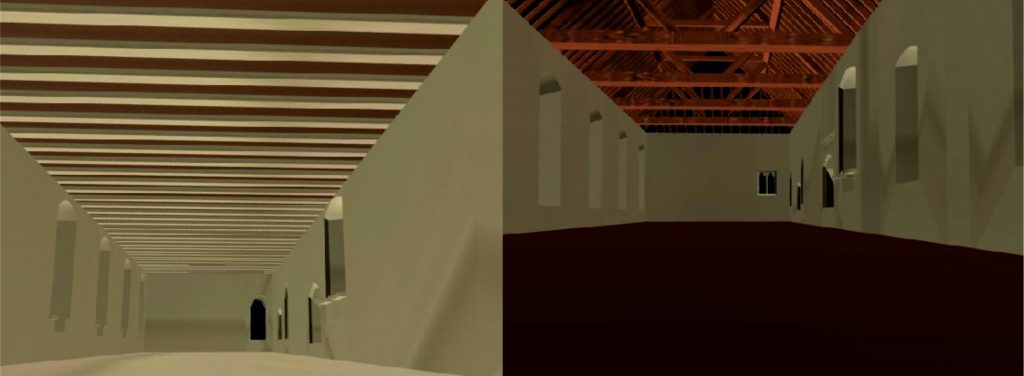

This can be seen when considering the private apartments on the eastern elevation. Previous interpretations[4] see them described as comparable; they lie one above the other and appear to consist of a similar layout of rooms; an unheated outer chamber, an inner chamber with fireplace and window seat, and a further inner chamber with fireplace. However, in 3D they begin to look very different; the roof converts the upper apartment; making the space much more open and the slightly different arragements of windows on the curtain wall combined with the position of the Great Hall will affect the outer chambers.

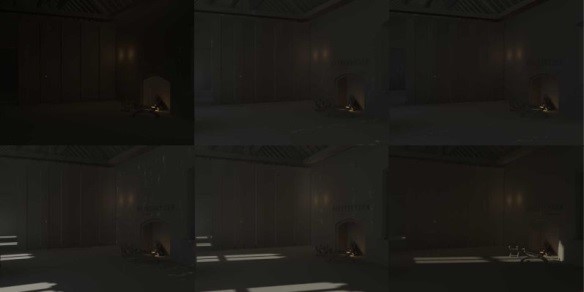

We can also use the models to consider the lighting of the spaces over the course of a day. A lighting analysis demonstrates how dark these rooms are and how they change over the course of the day.

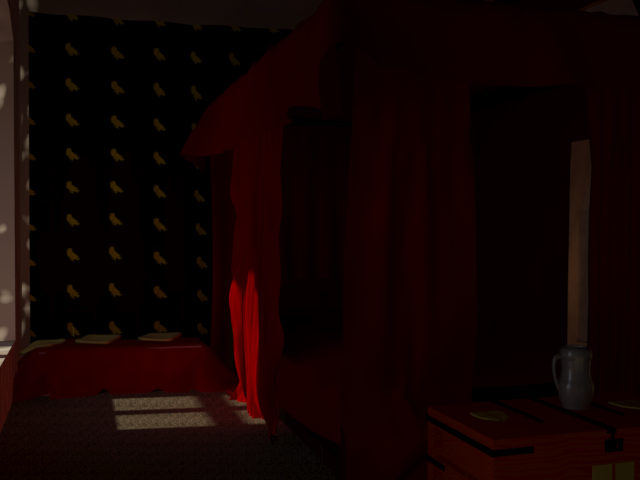

Finally, in furnishing the rooms we can consider movement through the spaces. Floor plan can allow us to see how spaces connect and their size. But in furnishing the rooms the movement through that space can be considered within the frame of reference of an inhabited building.

These examples show just some of the ways to consider how we are thinking about the use of space; in this case at Bodiam Castle and how it is beginning to raise new thoughts on the experience of living within the building.

[1] These drawings and the results of the project have recently been published Johnson 2017 available http://www.oxbowbooks.com/oxbow/lived-experience-in-the-later-middle-ages.html

[2] Faulkner, P. A. (1963). Castle Planning in the fourteenth century. The Archaeological Journal, 120, 215–35. DOI: 10.1080/00665983.1963.10854241.

Simpson, W. D. (1931). The Moated Homestead, Church and Castle of Bodiam. The Sussex Archaeological Collections, 72, 69–99.

[3] Johnson, M. H. (2017). Lived Experience in the Later Middle Ages. (M. H. Johnson, Ed.). St Andrews: Highfield Press.

[4] Faulkner, P. A. (1975). Domestic planning from the twelfth to the fourteenth centuries. In J. T. Smith, P. A. Faulkner, & A. Emery (Eds.), Medieval Domestic Architecture (Vol. 115, pp. 84–117). Leeds: The Royal Archaeological Institute.

Goodall, J. (2011). The English Castle. London: Yale University Press.

Nairn, I., & Pevsner, N. (1965). The Buildings of England: Sussex. London: Penguin Books.