Dr Michael Fradley, project lead for the CST funded project on Caus Castle in Shropshire examines one of the main interesting aspects of the project.

Looking back on our work at Caus Castle in Shropshire, funded by the Castle Studies Trust, one of the most interesting elements identified was the post-medieval redevelopment of the site. Given how little field research had taken place prior to our work in 2016, there were many new observations to be made, but the creation of ornamental gardens on the south slopes of the hill hinted at ambitions to develop a new elite landscape.

Subscribe to our quarterly newsletter

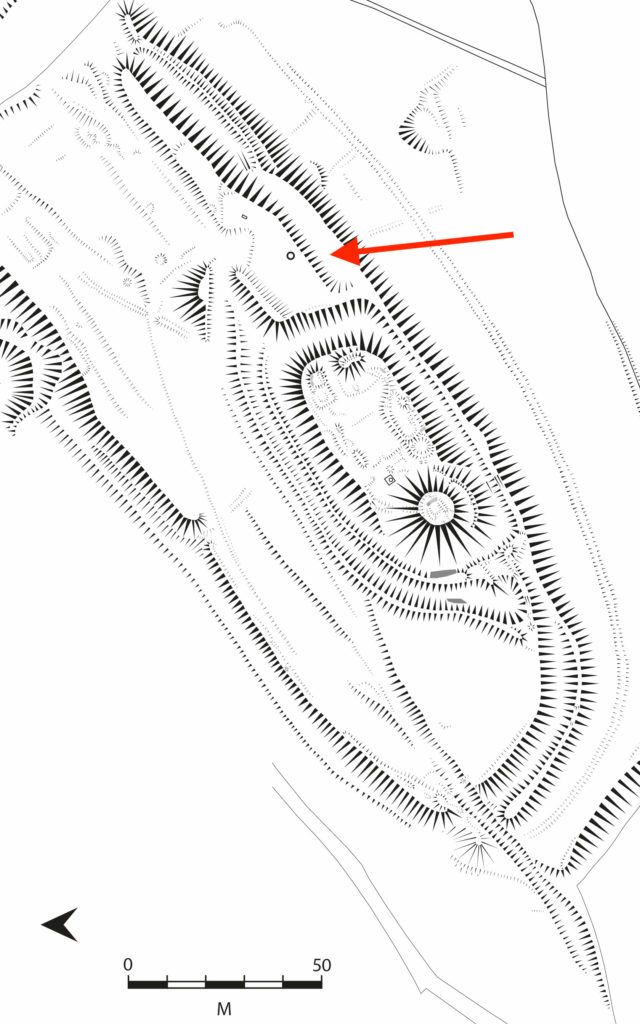

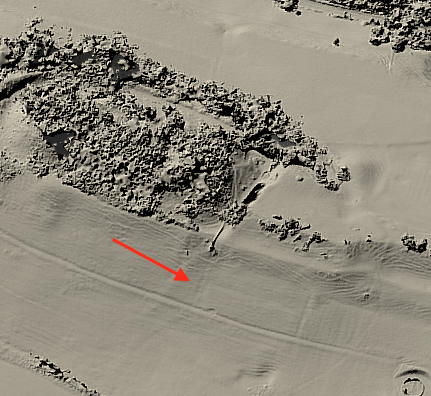

At its medieval height, the Corbet family had constructed an extensive castle complex, with views from the motte, great hall and southern wing of the castle bailey looking out across the wide Rea Valley to their hunting forests of the Stiperstone Hills. While these views would still have been important, archaeologically we can see a shift in investment into creating an immediate garden landscape on the sunny, southern-facing slopes of the castle. The shift away from the monumental defences that defined the medieval castle is demonstrated physically through the infilling of the southern ditch of the castle bailey to create a probable broad planting terrace (Fig 1). It seems probable that this process of creating an ornamental landscape at Caus began in the 16th or earlier 17th century, possibly under the Staffords, or more likely under Joan Thynne and her son Thomas.

The use of a digital photogrammetric model of the castle, using imagery collected by a drone-mounted camera, proved invaluable in this stage in identifying that further garden features may have extended further south beyond the original bounds of the castle. A square enclosure, fragments of which had been picked up by the ground topographical survey, was clearly visible on the digital model on the southern slopes (Fig 2). While less clear in function than the garden terrace, this feature would also seem to fit within an expanding garden complex.

While the totality of these garden features would seem small in comparison to earlier and contemporary examples of elite gardens developed around castle sites, as well as former monastic complexes and new country houses, Caus Castle was not a central residence of the Thynne family, which centred on Longleat in Wiltshire, and should also be seen potentially as a work-in-progress as a developing ornamental landscape. If investment had continued at Caus as an elite residence, we could perhaps draw a broad analogy with the development of Powis Castle in terms of a castle revival in the 17th century, in a geographically peripheral location that ornamentally made full use of its south-facing slopes (Fig 3).

Elite investment in Caus Castle appears to have ended in the 17th century, and while we are deprived of seeing what it may have become if it an been maintained as an elite residence and associated landscape, that development would have potentially destroyed much of the evidence of the medieval and earlier evidence. This snapshot of a castle in flux in the earlier post-medieval period does, however, make the site that little bit richer archaeologically.

Subscribe to our quarterly newsletter

Caus Castle is on private land and not open to the public