As work starts on the Caerlaverock Weathering Extremes project, Richard Tipping of the University of Stirling and Morvern French from Historic Environment Scotland explains what they hope to achieve the work involved in doing that.

Some 800 years ago, a newly built castle at Caerlaverock, on the Solway Firth, was abandoned and a new one was built higher up the hill. The first castle fell victim to climate change as huge coastal storms hit the Solway coast in the medieval period. This was the conclusion of University of Stirling researchers at Caerlaverock Castle in 2004. This May, with support from the Castle Studies Trust and Historic Environment Scotland, the same researchers are going back to Caerlaverock to gather more and better data.

Subscribe to our quarterly newsletter

The Weathering Extremes project will look in more detail at the impacts these storm surges had on the old castle at Caerlaverock, the landscape, and its people. This castle was constructed around 1229, 800 years ago. Then, the castle was on the coast and had a harbour, and it had an important role in protecting Scotland from Edward I and guarding the entrance to the River Nith and Dumfries. But in 1300, when Edward I invaded southern Scotland, he famously laid siege to a new stone-built castle, a couple of hundred metres inland and five metres or so higher. This is the castle that thousands of visitors see every year, one of Historic Environment Scotland’s most impressive and most-visited properties. As we recover from Covid-19, Historic Environment Scotland wants to enhance the visitor experience. This means learning more.

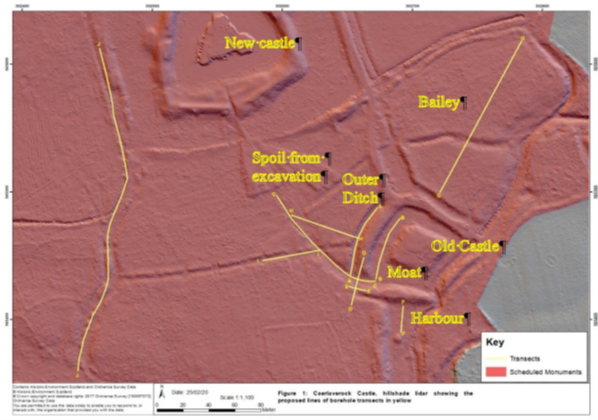

Today, the old castle, tucked at the bottom of the hill, is in an uninviting, ill-drained wetland. It was probably like this in 1220. The moat, earthworks, and ditches surrounding it all filled with freshwater peat. But suddenly, the peat-filled ditches were invaded by silt and clay. Analyses of microscopic organisms called diatoms, which are marine or freshwater algae, showed that the silt and clay was marine, coming inland from the coast, probably through the harbour. Huge storms seem to have repeatedly hit the coast, and large curved storm-ridges of gravel were piled up. Some gravel came from the west side of the Nith estuary, driven across by storms. New LiDAR imagery has detected at least seven ridges, each twenty to thirty metres wide and tens of metres long. When the storms ceased, the old castle ended up some 400 metres distant from the coast. This provides new evidence which wasn’t available when the old castle was last excavated two decades ago, and when combined with this new fieldwork we will know so much more about the chronology and impact of climatic events at Caerlaverock.

In 2004 the above features were dated by radiocarbon, but new techniques now allow radiocarbon dating to be much more precise. So, this year, Dr Richard Tipping and Dr Eileen Tisdall, environmental scientists at the University of Stirling, will go back to what they studied in 2004. They will study the sediments more closely and collect more and better samples, to trace the environmental legacy of the medieval storms. There is much we do not yet know. When did the storms first hit the coast and why did they begin? Had the builders already experienced the earliest of these but carried on building regardless, driven by military concerns, or did the climate change only after the old castle was completed? How long did the period of storm surges last – decades or centuries? How powerful were they? How far inland did they penetrate? The north Solway shore is low-lying, and floods could have extended for kilometres inland, as we know some did later in the ‘little ice age’. Do these past impacts have meaning for what is to come in the 21st century?

Subscribe to our quarterly newsletter

In this initial stage of the project, Dr Tipping will establish a series of transects across the site and will then extract cores and samples for sediment description and stratigraphic analysis. Cores taken from the inter ridge basins will be used to locate in situ plant remains. More fieldwork will take place in the summer with Dr Tisdall and Dr Tim Kinnaird when further cores will be taken from the harbour and the outer moat of the old castle. Selected samples will later be subjected to radiocarbon dating and pollen and diatom analysis. Samples from the harbour will be optically stimulated luminescence dated by measuring the level of ionising radiation stored within the sands from exposure to light. From this we can calculate the last time the mineral was exposed to light, therefore finding out the dates of the sand deposits and the final period of the harbour’s use. We hope to have the first laboratory results later in 2021, with the final results due in spring 2022.

This fieldwork will enable us to better understand the use of the wider landscape at Caerlaverock, including medieval responses to climate change events and access to the coast for travel and trade. It will also tell us more about the medieval people who built the two castles, their experiences, and their motivations in locating the castles where they did.

Before visiting Caerlaverock Castle please check the website to see if it is open and to book a time to enter: https://www.historicenvironment.scot/visit-a-place/places/caerlaverock-castle/