During the summer of 2022, Wakefield Council and Wessex Archaeology undertook several geophysical surveys of Pontefract Castle funded by the Castle Studies Trust. Ian Downes, Senior Heritage Officer at Wakefield Council explains what they found.

We were trying to discover if there were traces of the castle’s rich archaeology hidden under the ground. Specifically, we were looking for several service buildings between the kitchens and Royal apartments which had been mentioned in maintenance records for the castle, Victorian paths listed in ordnance survey maps, as well as any evidence of buried weaponry from the Civil Wars bombardment in the 17th century.

Subscribe to our quarterly newsletter

This was not the first-time surveys of this nature had been conducted, most recently West Yorkshire Archaeology Service were commissioned back in 2010.

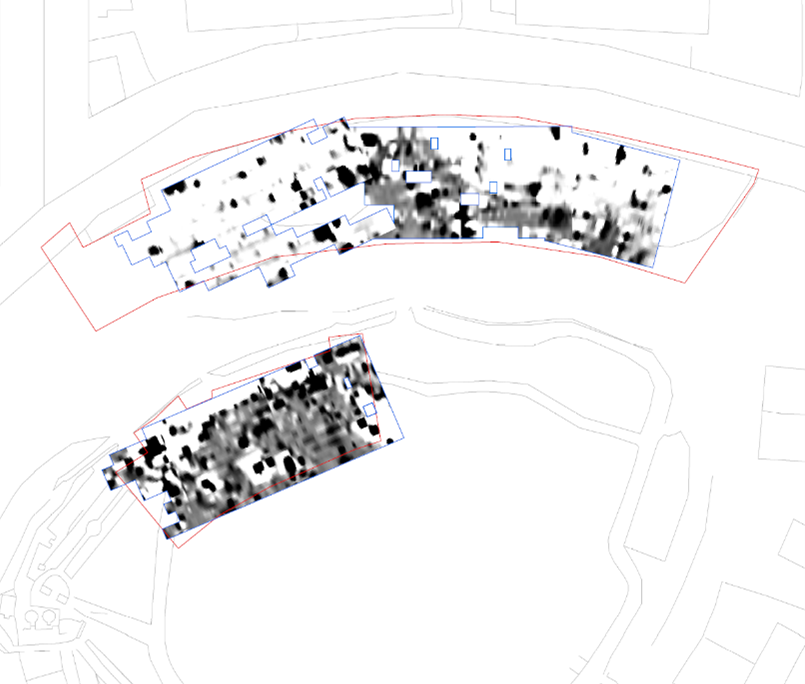

Three techniques have been utilised here: Resistivity, Magnetometry and Ground Penetrating Radar.

Resistivity measures the ability of the ground to conduct an electrical signal between two metal probes. In its simplest form this gives us a clue about buried walls and ditches, as the latter holds water much better than a wall and the resistivity is lower. This technique is relatively quick, easy and cost effective, but has limited depth and tends to only reveal that which is relatively close to the surface.

Magnetometry, or to be more specific magnetic gradiometry, records tiny variations in the earth’s magnetic field. These could be caused by the filling in of a ditch, a fire or magnetic items in the soil. This again doesn’t have a great depth but can help backup findings from our other two techniques. The ability to spot iron objects on a Civil Wars site that was bombarded by cannon fire is also useful.

Our third method was ground penetrating radar. It uses a form of electromagnetic radiation similar to that used in radios, microwaves and mobile phones and employs the same technology used to detect aircraft. However, instead of sending signals into the air we direct them into the ground and measure how long it takes for those waves to bounce back. The signal bounces back better from solid objects than soil, so it can help spot buried walls or pits, and the time taken to receive the signal tells us how deep down they are

Results

We had varying success with the surveys. Unfortunately, outside the curtain wall, where we hoped to find Civil Wars evidence, the surveys didn’t show any clear results. There were more anomalies below the queen’s tower than elsewhere, but this may be the result of later landscaping works to accommodate the later road around the castle.

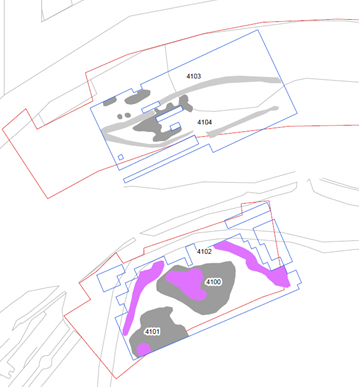

The resistivity survey however had more success. Here we can see evidence of the modern paths (pink) and the remains of an elliptical path in the northern survey area which matches the design of a Victorian path system, seen in an 1881 ordnance survey map. No images survive of these paths, so it is exciting to find some evidence of their existence beyond the original plans.

The final survey technique, using deeper ground penetrating radar, shows a large grey area which is also seen on the resisitivity survey above. Its undefined shape and proximity to the surface suggests it is possibly rubble. However, it’s the dark orange feature about 1m down that is by far the most revealing.

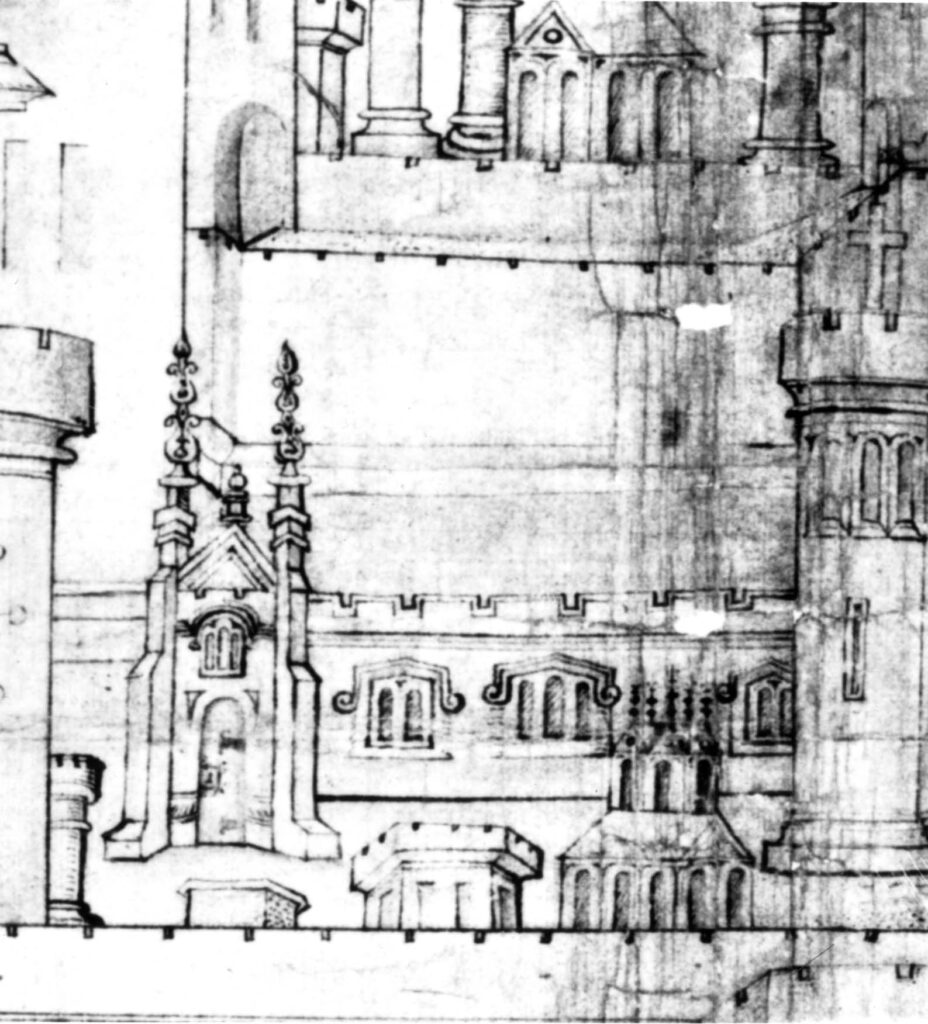

For us, this was an exciting and unexpected discovery, as the design and shape of the structure, including the buttresses on the corners, closely matched a building seen on a 16th century drawing of the castle by Ambrose Cave. He had been commissioned to survey the castle for Queen Elizabeth I in 1560 and it shows a number of buildings along the same section of curtain wall, including the small entrance porch, seen below with the elaborate pinnacles.

We believe it shows a 15th Century chapel that replaced the Norman Chapel which can be seen in the Eastern corner of the bailey. It was assumed from this drawing that it stood away from the curtain wall which can be seen in the background.

However, the design of its entrance closely matches the shape found in the radar survey, including the buttresses on the corners. Its possiblelocation now suggests that it was built against the curtain wall like the other buildings in the castle and was perhaps shown just forward of it for simplicity.

To have been able to finally locate this building and with such clarity and certainty is an exciting discovery for us. This new evidence adds to our knowledge and understanding of what used to be one of England’s greatest castles and will help to inform future interpretation of the site, provide a focus for potential future fieldwork and finally solves the mystery of where the 15th Century chapel actually is!

We are extremely grateful to the Castle Studies Trust for their funding which allowed us to carry out the geophysical surveys. We also acknowledge the support of Wessex Archaeology and West Yorkshire Joint Services in the production of this article.

You can find out more about the project in our short videos which can be found on the Castle Studies Trust Youtube channel