In the first of two blog posts Coralie M Mills and Hamish Darrah of Dendrochronicle look at how they managed to test and date a piece of timber found in a wall socket of the tower at Old Wick Castle, Caithness. A second article by Dr Will Wyeth will look at the historical context behind these surprising findings.

A single surviving timber fragment in the ruinous tower of Castle of Old Wick in Caithness was recovered, studied and dated through the support of the Castle Studies Trust for this Historic Environment Scotland (HES) project. The outer end of the timber was visible within a socket in the north west wall of the tower at about second floor level. Exposed to the elements, in fragile condition and at risk of further decay, it was recognised by HES as a means of dating this relatively featureless tower, variously ascribed to the 12th or later 14th century for initial construction. Therefore, our mission to recover this fragile lone timber was rather nerve-wracking and undertaken very carefully. Fortunately, it went well, and we recovered it in one piece in September 2021.

Subscribe to our quarterly newsletter

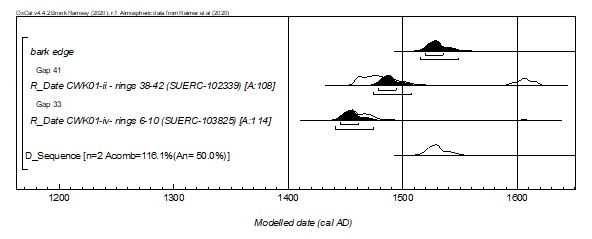

Back at base we recorded the form of the timber and sub-sampled it for dating and species identification. The sampled cross-section had two centres and was intact to sub-bark surface in one corner. The species proved to be alder (Alnus glutinosa), a common native tree of wet places including in northern Scotland. This ruled out the possibility of dendrochronological dating, given the absence of suitable alder reference data, and led to Bayesian radiocarbon ‘wiggle-match’ dating using five-year blocks of rings sub-sampled at known intervals across the 80-year tree-ring sequence. The radiocarbon dating was undertaken by SUERC and Bayesian analysis of the only two viable sub-samples provided a ‘wiggle match’ date of cal AD 1515–1550 (95% probability), with highest single-year probabilities in the range cal AD 1515–1535 (68% probability). The results represent the bark edge position and the felling date of the timber. There is a possibility this is naturally storm-thrown material being used rather than a tree being felled for the job, in which case the date is the death date of the stem, but either way it is unlikely this stem was dead for long before it was worked.

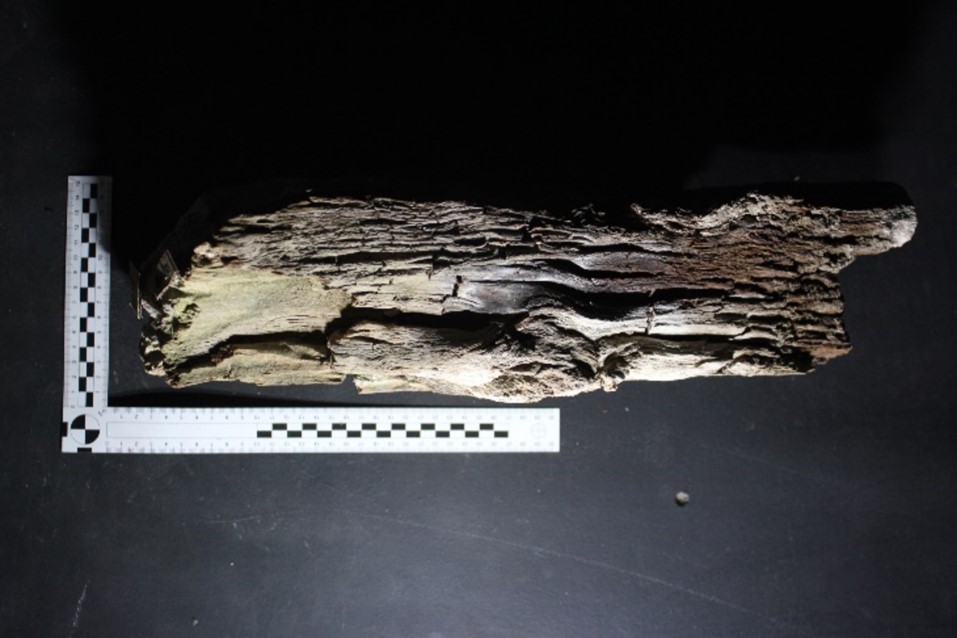

This is a short irregular length of timber, 46cm long, 12cm wide and a maximum height of 19.5cm at the exposed face, tapering to 6cm at the inner end. The outer face is heavily weathered, and we cannot tell whether that face was worked or how far the timber projected originally. At the better-preserved inner end, the timber has an axe-cut notched, faceted face which had no structural function in the socket and was just sitting free within the void behind the timber. It has no clear joinery evidence such as a mortise or trenail. Therefore, our preferred interpretation is that the notched end is the consequence of axing off the branchy top of the stem, but we cannot rule out the possibility that it represents a re-used timber. If the notched end is seen as a deliberate feature, then it may have been designed to allow this timber to be propped against another element of a structure, perhaps in something temporary like scaffolding, and could signify re-use of the timber in this context. Other than this notched feature, the only other woodworking evidence is of an axe being used to shape the timber from the round into a rectangular form.

Photo: Hamish Darrah 30.09.21.

Alder is often naturally multi-stemmed and can also be coppiced. However, eighty years is well beyond the stem age expected in any coppicing system. This is more probably natural unmanaged material. Based on the overall form, the double centre, the direction of knots and the taper on the timber, we do not think this timber is cut from a managed coppice stool or the base of a tree but rather from the upper branching top of a substantial stem. Therefore, the stem could have been a good bit older than 80 years when felled, as any tree stem will have more rings near the base than at the top. The stem must have been several metres tall after 80+ years of growth. Therefore, while we do not know how long the original timber was, this surviving short length of timber may be an offcut, with the bulk of the stem used for another purpose. Alder sill beams have been found in medieval Inverness and Perth, perhaps selected for alder’s rot resistant properties, and alder is also known to have been used as crucks historically in northern Scotland.

The socket holding the timber is much deeper than the timber, at least 70cm deep, with packing around the timber and a void behind, suggesting the socket was not built with the dimensions of this alder timber in mind and may be earlier than the timber, which would make the timber part of a secondary feature. Based on our observations of the timber’s position and character, it is clearly not part of a floor joist, and is more likely a fixture for a lost internal fitting or small structure. If the timber was used fresh in this context, our preferred interpretation, the dating results represent the time when this timber fixture was added to the castle. However, if the notch is interpreted as evidence of timber re-use than the date is a terminus post quem (date after which) for this phase of alteration to the castle. The structural and historical evidence is considered further by Will Wyeth in his separate blog piece:

One thought on “Castle of Old Wick: The tale of a tower, a timber and time”