As Drs Richard Tipping and Eileen Tisdall along with Dr Tim Kinnaird of St Andrews return to Caerlaverock to carry out their final piece of field work this Saturday (2 October), Richard Tipping discusses what has happened so far.

Background

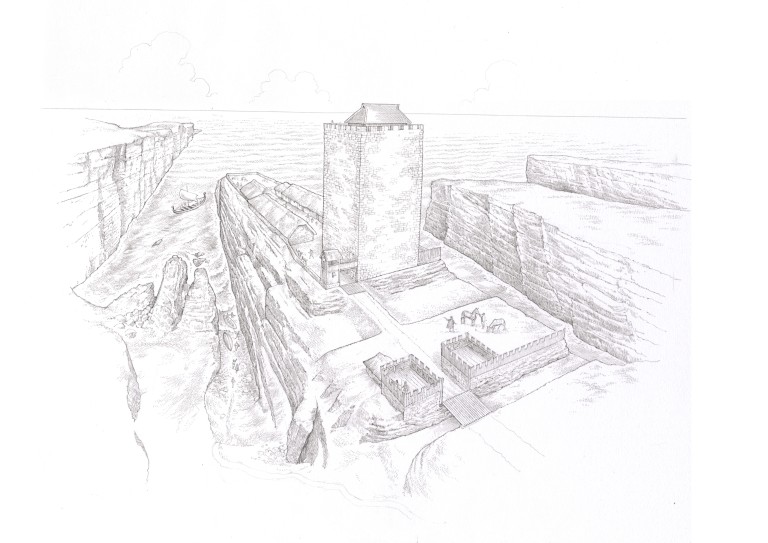

Earlier blogs have described the fieldwork, over the summer, at the Old Castle at Caerlaverock in south west Scotland. We have been testing the idea that several very large storm surges impacted the castle, persuading the occupants to re-build, higher up and further inland. That fieldwork involved recording sediments in the moat (Figure 1) and surrounding ditches, confirming that these sediment traps are full of silt derived, we think, from storm surges pushing sediment from the coast, through the harbour and into the moat. We’re checking the origin of the silt from diatom analyses, which can define water salinity. But we hadn’t found evidence that these storm surges were destructive, impacting archaeological features. Now we think we have.

Subscribe to our quarterly newsletter

Setting

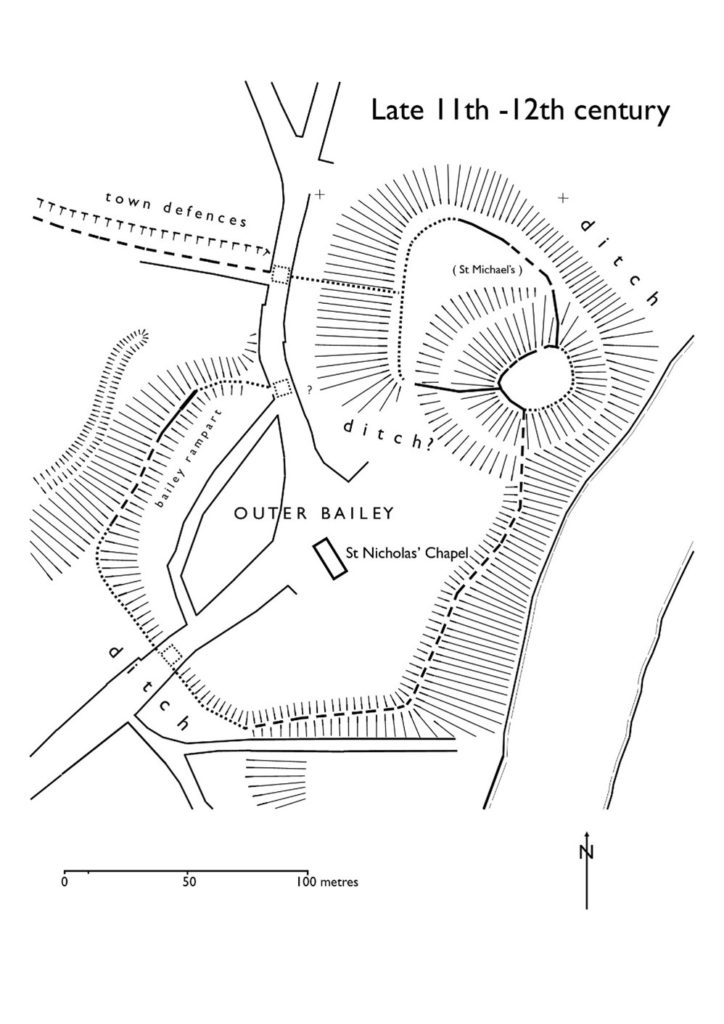

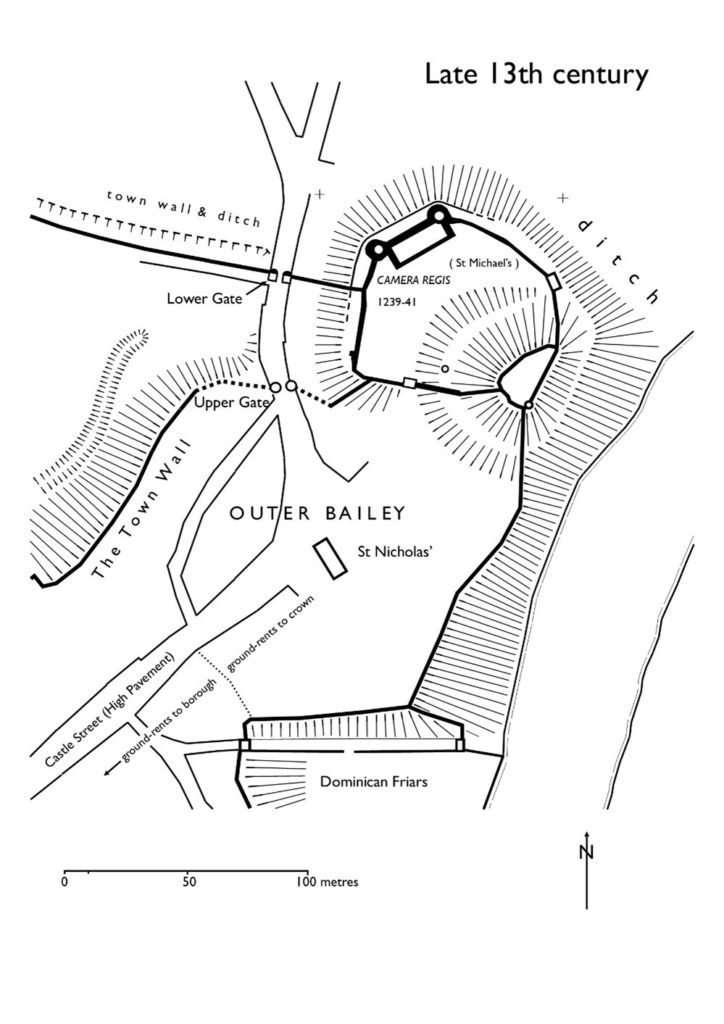

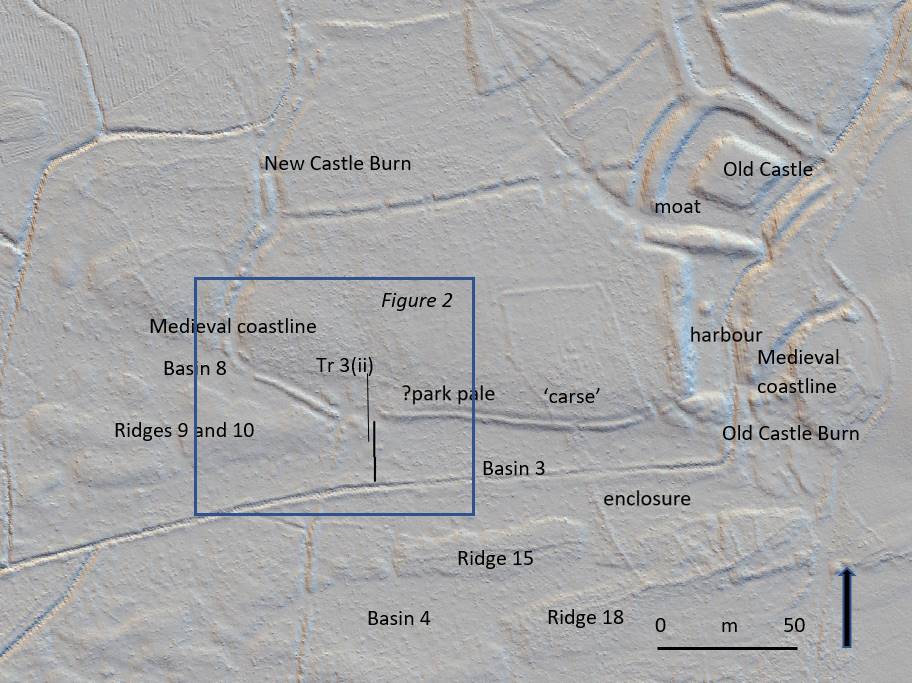

The ‘park pale’ is the name given to a ditched-&-banked enclosure that extends west from the harbour at the old castle for several hundred metres (Figure 1). It was constructed along a small cliff that marked the medieval coastline, separating mid-Holocene estuarine sediment, called ‘carse’ to its north and a series of very broad, parallel east-west trending ridges and basins constructed by medieval storm surges to its south (Tipping and Adams 2007).

In Figure 1, a LiDAR image, Ridges 9 and 10, and Ridges 15 and 18 are seen. Between them, lagoon basins were trapped: Basins 8, 3 and 4 here. Some basins will be radiocarbon dated because peat formed when they were isolated from wave action.

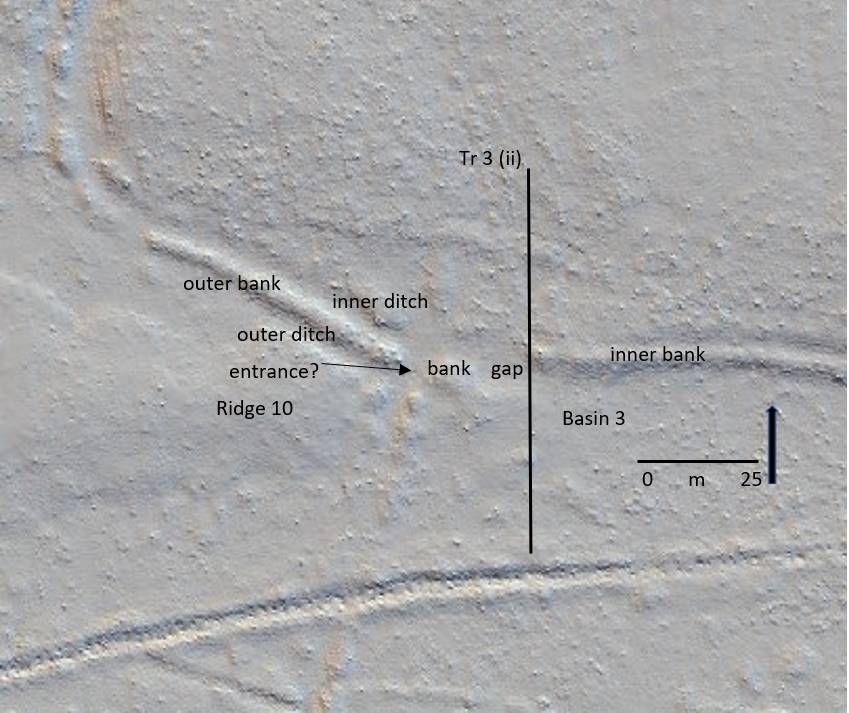

In detail (Figure 2) the ‘park pale’ is complicated. There is an inner bank to the east, with a crest around a metre higher than the ground to its south. This is lost at a 25m wide gap and cannot be traced further west. Instead, a second, lower outer bank continues north west to the New Castle Burn (Figure 1). The outer bank has, in places, an outer and inner ditch. Another, 4m wide gap may be what Brann (2004) thought was an entrance.

Tr 3 (ii) is the line of a 50m long sediment-stratigraphic transect of 24 hand-sunk boreholes from the ‘carse’ in the north, which the inner bank rests on, south across Basin 3 to the canalised Old Castle Burn. The transect was designed to test the idea that the 25m gap in the ‘pale’ is an erosional feature from storm surge impacts.

Stratigraphy

What Tr (ii) shows is that the low ground of Basin 3 is floored by bedrock less than a metre down. This is covered by well-sorted sand and then by poorly sorted coarse to very coarse sand and grit with common pebbles.This fills Basin 3, thickening shoreward. This is interpreted as a storm surge deposit, deposited in a high-energy marine environment. Boreholes on the inner bank, a metre higher than Basin 3, and 25m inland, also recorded thick gravelly sand, impenetrable at 90cm depth on the inner bank. This thins north but is still found 20m inland from the medieval coastline.

Narrative

There were at least two storm surge ridges formed before the events recorded in Basin 3. Basin 8 (Figure 1) was formed by the second storm surge, as yet undated. This created Ridges 9 and 10. These broad gravel ridges in turn protected the western ‘park pale’ from subsequent marine erosion (Figure 2). What is now the outer bank, with its associated ditches, probably represents the original boundary of the ‘pale’. The ‘pale’ pre-dates the storm surge event described here. It is shown by the sediment stratigraphy to be, broadly, medieval in age and, broadly, contemporary with the old castle.

Eastward, Ridges 9 and 10 merge with the ‘carse’ of the medieval coastline, leaving this part of the coast vulnerable to later storm surges. At this point, the outer bank of the ‘pale’ is lost. In its place are storm surge sediments. The ‘pale’ was eroded by the storm surge. This storm surge pushed at least 90cm of gravelly sand north onto the surface of the ‘carse’. The cliff may have been formed after this storm surge, by later erosional wave action. Gravelly sand was pushed or thrown 20m beyond the cliff. Waves also scoured the easily eroded ‘carse’, lowering the surface by around 0.5m, up to 100m inland.

Subscribe to our quarterly newsletter

References

Tipping, R. and Adams, J. 2007. Structure, composition and significance of medieval storm beach ridges at Caerlaverock, Dumfries & Galloway. Scottish Journal of Geology 43, 115-123.