After two decades of research into Marlborough Castle, the Marlborough Mound Trust has collated all the results of their work in to a new publication. Here, Richard Barber of the Trust looks at what they have found.

Marlborough Mound is one of the least visible of the great monuments of England, and almost unknown except to local historians and specialists. It stands in the middle of Marlborough College in Wiltshire, and even for generations of members of the school, it was no more than a mysterious but familiar presence, largely concealed by trees, and with nothing to explain what it is or why it is there.

In the last twenty years, the curiosity of one Marlburian, Eric Elstob, who set up a trust for its systematic restoration and the exploration of its history, has led to dramatic results. The key moment came when the Marlborough Mound Trust was offered the use of a coring machine by English Heritage, who were investigating the structure of Silbury Hill six miles down the Kennet valley. They wanted to see if the Mound was comparable to their site. As a result, we now know, thanks to the dating that radiocarbon analysis has enabled, that it is the second- largest Neolithic mound in the whole of Europe, broadly contemporary with Silbury Hill, and thus part of the much-vaunted ‘Stonehenge landscape’.

Subsequent research by Jim Leary has shown that Marlborough is currently the only known example of the reuse of a prehistoric mound as a castle motte. However, only a few traces of the foundations of the medieval castle survive. We have nothing of the keep which once stood on the Mound. So here the question was not of archaeology – several trial pits were unsuccessful – but of historical research. Initially in the hands of the family of William Marshal, (whose family retained a connection with the castle as late as 1297), the records in the National Archives enable us to reconstruct many of the details of the vanished buildings.

However, the use of the castle in the early thirteenth century is a much richer story. To take one example, John sent the queen and his children to Marlborough for safety just before the signing of Magna Carta. For Henry III, it was one of his most favoured residences outside London, and he spent a total of about two years there in the first three decades of his reign. His love for Eleanor of Provence is reflected in the costly refurbishment of the royal chambers in the castle. There is also evidence of ‘herbers’, the small courtyard gardens found in other royal castles of this period.

After Henry III’s death, the castle passed to Eleanor, and thereafter was part of the dowry of English queens until 1548. It began to decay shortly after Eleanor’s death [insert date], when part of the great tower collapsed, and by 1400 the whole castle was more or less deserted. The meagre list of royal property there in the fourteenth century is matched by accusations against the local rector who had surveyed the castle in 1371, which described how he had removed material from the site to build his own houses. By 1541, when John Leland came to Marlborough on his great journey round England recording its antiquities, only the remains of the keep were still prominent.

One other interesting element at Marlborough castle was the fishpond. The ‘king’s great fishpond’ survived unidentified until a year or two ago, when it was filled in (and now appears to be a paddock for polo ponies). It was a major source of supply for freshwater fish such as bream – not to be confused with sea bream – and pike. Henry and Eleanor, however, preferred lampreys, finding all other fish ‘insipid’. The fishponds also supply breeding stock for other castles, shipped in water-filled barrels.

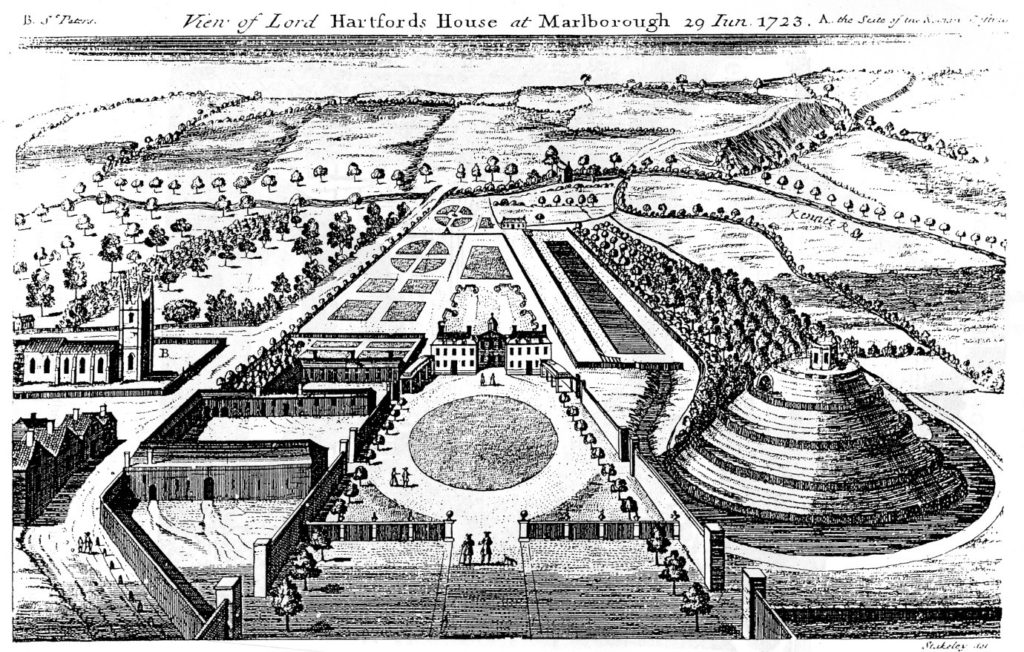

The last stage in the Mound’s history was its adaptation, probably in the decade before the civil war, as a major feature in the garden laid out by Francis Seymour, the owner from 1621 and builder of the first house on the site of the Castle. A spiral path and a grotto were cut into it, possibly in the 1640s. The Mound was well maintained when Marlborough College took over the house in 1843, but later photographs record steady decay and encroaching trees. A water tank was installed on the top early in the seventeenth century, which had become a massive cast iron and concrete structure after the second world war, surrounded by a jungle of undergrowth.

The Mound Trust’s work over the past twenty years has restored something of the impressive aspect of the original mound, and this newly published book presents a fascinating picture of the history of the hidden treasure in the heart of the College.

The Marlborough Mound: Prehistoric Mound, Medieval Castle, Georgian Garden

Copies are available to followers of the Castles Studies Trust at £25 direct from the publisher, Boydell and Brewer Ltd, on their website (until December 31 2022) at:

https://boydellandbrewer.com/9781783271863/the-marlborough-mound/

Use code BB072 when completing the order. Normal price is £45.

ISBN 978 1 78327 186 3, 234 pages, 234 x 156 mm, 54 illustrations.

Subscribe to our quarterly newsletter