With the final report in the curator of Raby Castle, Julie Biddlecombe-Brown, gives an update on the building survey of the castle the Trust helped fund in 2022 and offers an opportunity for scholars to review it.

In 2022 the team at Raby Castle was fortunate to receive a grant from the Castle Studies Trust to digitally scan the castle exterior. Initially for research and interpretation, the scan has quickly proved to have multiple benefits and uses, and will undoubtedly have more to come. Alongside the scan, Raby (on behalf of Lord Barnard) commissioned an archaeological building survey, carried out by Durham University Archaeological Services and led by Senior Archaeologist Richard Annis, completed last year but updated in January 2024 when able to enter some previously inaccessible areas.

Subscribe to our quarterly newsletter

There had been limited scholarly research into Raby Castle in the past; the most comprehensive history having been written by the 4th Duchess of Cleveland in 1870, drawing largely on antiquarian sources. As such, much of the story of the development of the castle has not been verified by current archaeological research methods, so alongside the survey of the fabric, by Durham University Archaeological Services, the castle team set to work exploring the archives and tracking down the sources used by antiquarians.

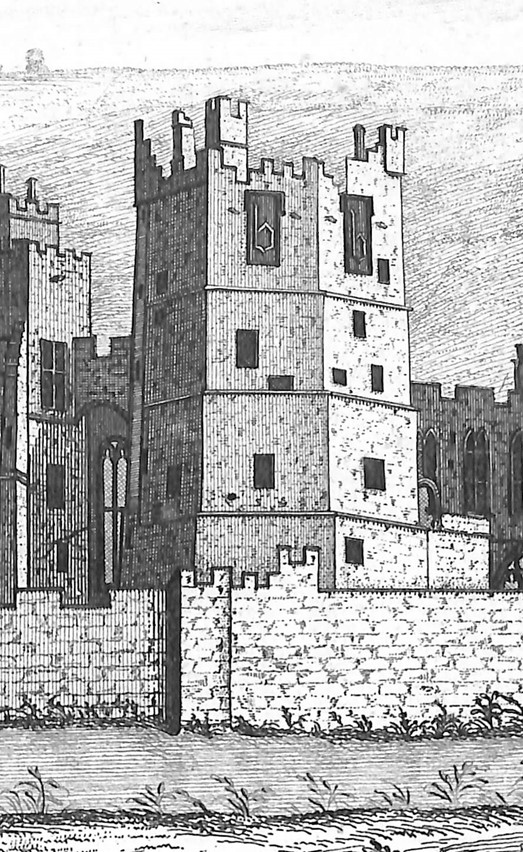

The site has been occupied since before Domesday Book; the earliest record comes from the reign of Canute when Rabi was part of a gift offered by the King to the shrine of St Cuthbert in Durham. Although no trace of the early medieval structure is in evidence, it is from the later middle-ages, predominantly the 14th century when the castle was owned by the Neville family that the castle developed into the magnificent structure you see today, described by architectural historian Robert Billings in the 19th century as “the most perfect of our Northern Castles, retaining in the mass all its ancient features” … if only it did! Later developments from the 17th century onwards by the Vane family – later Barons Barnard (and even later the Earls of Darlington and Dukes of Cleveland) – who still own the castle today are well documented in the castle archives.

But apart from the castle itself, our sources for the Nevill period are limited. At some point, presumably after the attainder of Charles, 6th Earl of Westmorland for his part in the Rising of the North in 1569 or during the early years of ownership by the Vane family (purchased 1626) the documentary records for the earlier centuries of the castle were either taken away or destroyed.

One of the best early descriptions of the castle comes from the 1540s when it was still owned by the Nevilles. It was sources like this that we were keen to check against the findings of the recent survey. John Leland, in his survey of 1535-1543 wrote …..

“Raby is the largest castel of logginges in al the north cuntery, and is of a strong building, but not set other on hill or very strong ground.

As I enterid by a causey into it ther was a little stagne on the right hond: and in the first area were but 2. tours, one at each end as entres, and no other buildid; yn the 2. area as in entering was a great gate of iren with a tour, 2. or 3. mo on the right hond.

Then were l the chief tours of the 3. court as in the hart of the castel. The haul and al the houses of offices be large and stateley; and in the haul I saw an incredible beame. .. The great chamber was exceedingly large, but now it fals rofid and devidid into 2 or 3 partes. I saw there a little chamber wherein was in windowed of colerid glass al the petigre of the Nevilles: but it is now taken down and glassid with clere glasse.

There is a touer in the castel having the mark of 2. capitale B from Berthram Bulmer.

There is another touer being the name of Jane, bastard sister to Henry the 4 and wife to Ralph Neville the first Erl of Westmerland.

There long 3. Parkes to Raby whereof 2. be plenished with to 92 dere. The Middle Park hath a lodge in it”. (Toulmin Smith, 1907).

Even with the later alterations to the castle, Leland’s description clearly gives an accurate depiction of surviving medieval structures but also lost features. Pleasingly stained glass windows depicting both Neville crests and those of the families connected by marriage were incorporated in the vast Barons’ Hall extension windows in Burns’s alterations in the 1840s.

Equally interesting is the fact that other antiquarian sources appear, thus far, to be generally accurate. Although no trace has been established (yet), it is likely that the earliest structure was an unfortified manor house in the 11th century from which the castle developed ‘organically’, particularly in the 14th century when in phases, a double hall, solar tower, great chamber, private or refuge tower, chapel, postern gate and towers for servants, retainers and guests were added, believed to be the work of the John Lewyn whose hand can be seen in so many north-eastern castles. The kitchen tower is particularly significant, with its high domed ceiling, clearly linking to Lewyn’s work for the Bishop of Durham in the Prior’s Kitchen, Durham Cathedral.

Being in the Durham Palatinate, Raby’s License to Crenellate was granted by Bishop Hatfield in 1378, probably at the end of a phase of fortification which saw the structure emerge as a late contender for a somewhat irregular concentric castle.

How does the castle development relate to the habitation and family fortunes of the Nevilles in this early period? Interestingly, periods of the castle’s development can be linked closely to social mobility, often brought about by advantageous marriages to wealthy heiresses. Around 1176 Isabella de Bulmer married Geoffrey Neville bringing vast land in Durham and Yorkshire to the family. Bulmer’s Tower still bears that family name, adorned with a carved lower case ‘b’ towards its highest points. Later, Elizabeth Latimer, second wife of John, 3rd Baron Neville KG, similarly brought her fortune to the family on her marriage in 1381 and her family coat of arms is proudly displayed on the Neville Gateway – the main entrance to the castle complex along with the Neville saltire and the emblem of the Order of the Garter, a very visible reminder of the position and prominence of the family.

External events also had their impact on the development of the Neville stronghold. The wars with Scotland in the 14th century and particularly the Scottish raids south of the border resulted in increased security measures and fortification for those who could afford it. John Neville and his father Ralph had both played a part in the Battle of Neville’s Cross in nearby Durham (albeit John watching as a child): A victory for English troops but a constant reminder of the need for defence.

Subscribe to our quarterly newsletter

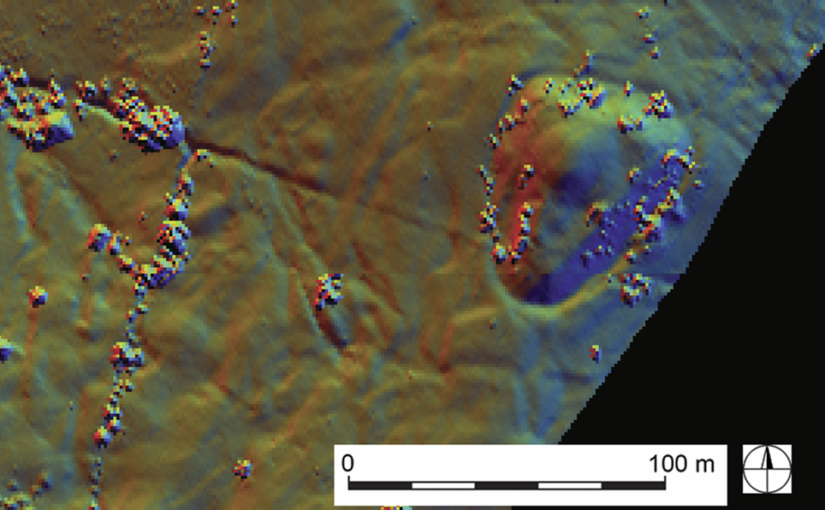

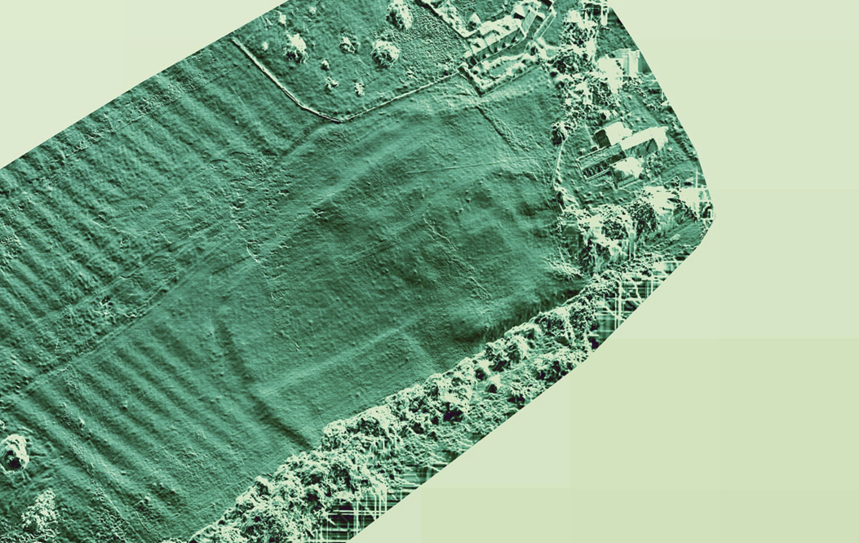

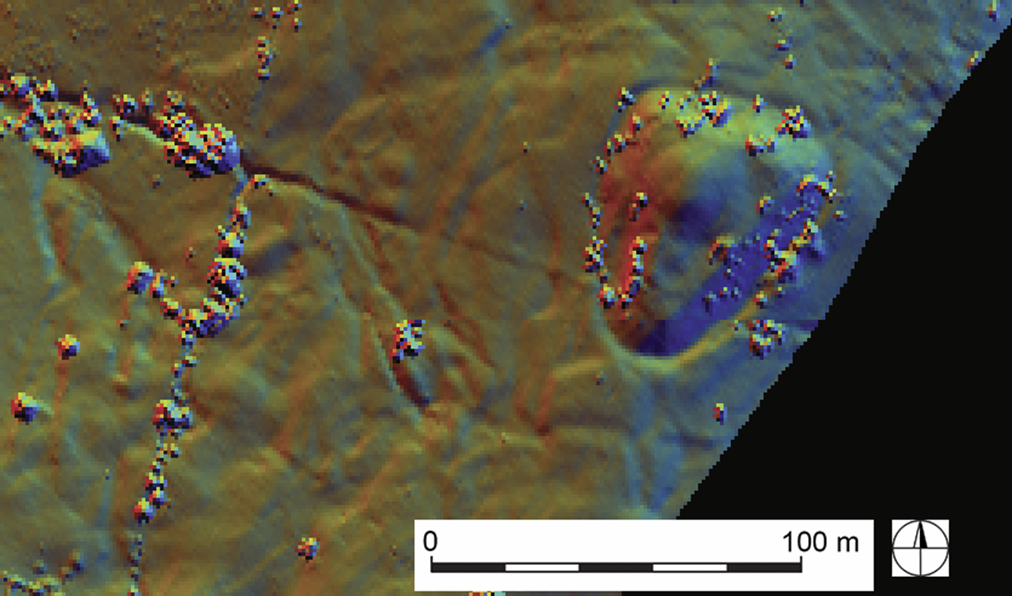

The ongoing research into the sources that provide context and meaning to the incremental development of the castle work hand in hand with the survey produced by Durham University Archaeological Services. It has been particularly pleasing to begin to explore some of the lost features, from the 3rd ‘court’ (courtyard) now located to the north of the Hall range to the puzzling configuration of spaces above the much-altered chapel gateway. The myth of the earlier towers and particularly the more unusual shape of Bulmer’s Tower have been explored, along with an identification of a list of features lost to 18th and 19th century development.

At the time of writing, our initial plans to incorporate the model in a new introductory film at the castle are well underway. Film makers Heritage Interactive have incorporated views of the castle in the draft film due to be installed for the 2024 season and we’re currently looking at making more use of the model to create a more detailed approach to digitally recreating the phased development of the site. The scan has also been used by the castle’s quinquennial architects and castle team as part of the inspection and maintenance of the castle and master planning for future activity.

Inevitably, the survey report, model and associated research leave us with more tantalising questions, but the report pulls together and verifies a fascinating plethora of information which had previously been scattered, hearsay or completely unknown! Raby welcomes further scholarship and investigation, building on the work of Richard Annis, Durham University Archaeological Services and indeed Raby Castle’s Curation and Archives team. Thanks to all involved! Scholars wishing to consult the report should apply to the curator, via admin at raby.co.uk