In her new book Authority, Gender and Space in the Anglo-Norman World, 900-1200, Dr Katherine Weikert, Senior Lecturer in Early Medieval European History at the University of Winchester looks at how medieval manors reflected and shaped – and were shaped by – their occupants to express social authority. In this article she looks at the facinating if little known Motte d’Olivet.

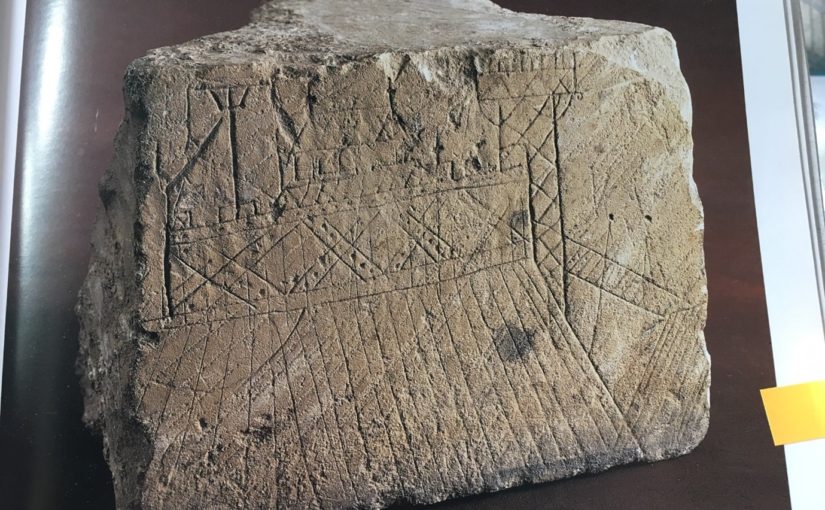

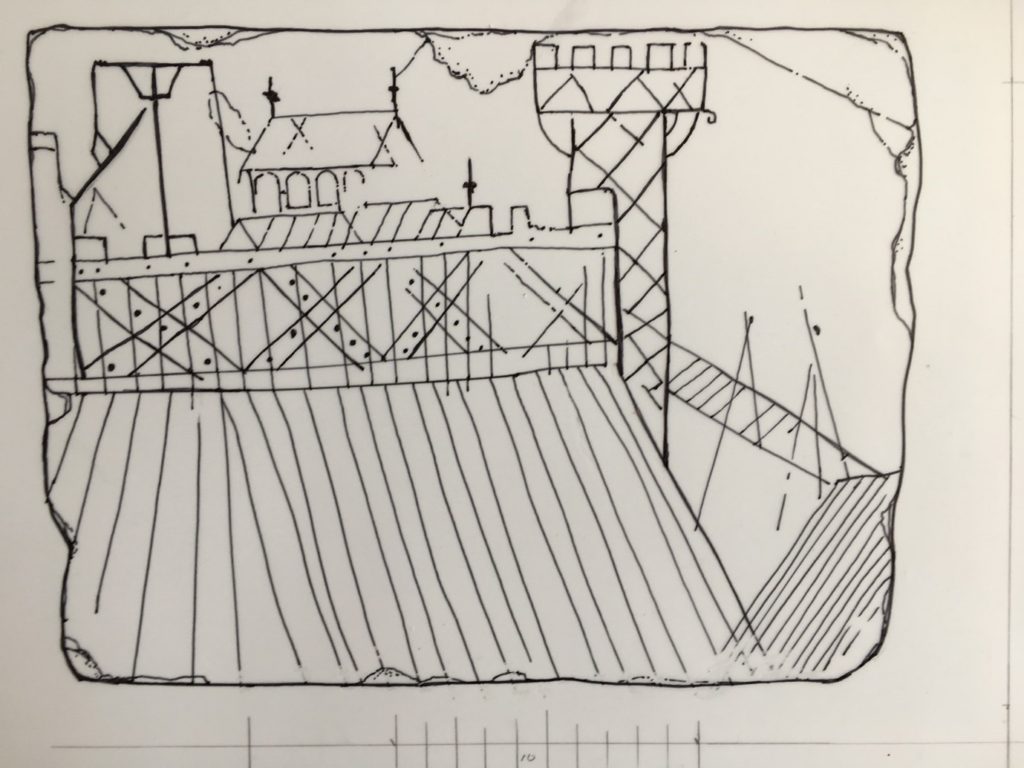

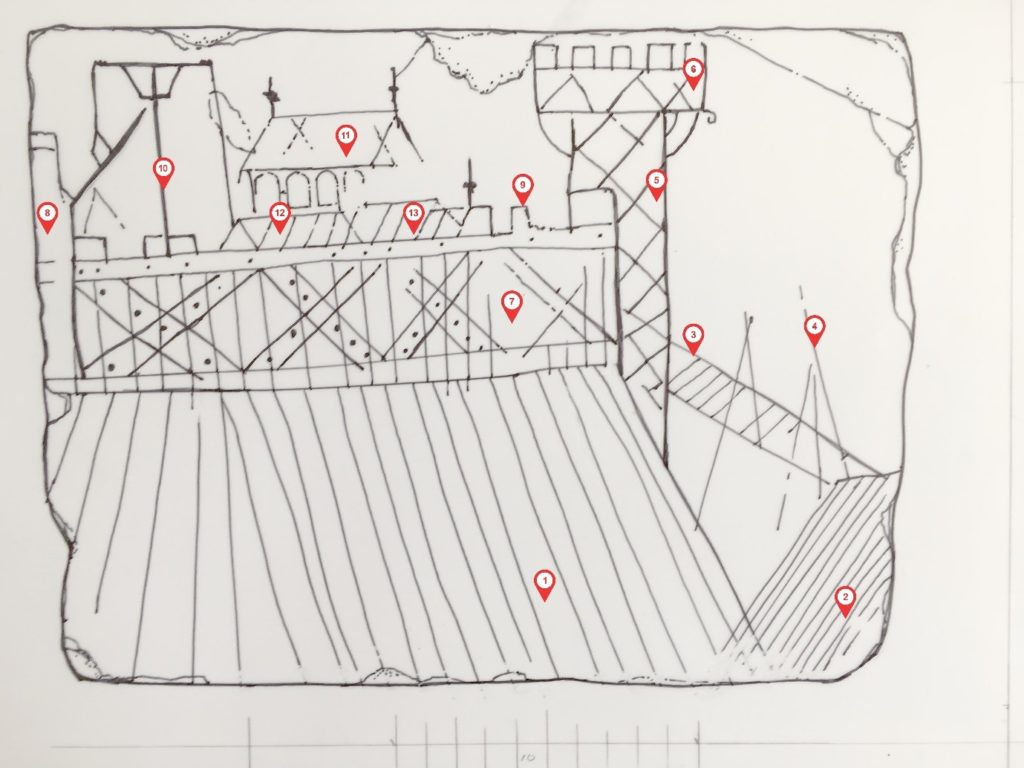

High in the lush forest of Grimbosq, Normandy, the remains of the Motte d’Olivet sit atop a lofty spur overlooking the Orne River valley. About twenty-two kilometres to the south of Caen, it’s a site that would be familiar to many castle-lovers: a man-made earthen mound, atop which formerly stood a wooden tower, with baileys on either side of it. A deep ditch around the motte kept it spatially and physically separated from both baileys. The motte-and-baileys take up the cramped, flat space on the point of the v-shaped spur surrounded by steep drops and small rivers on both sides (one charmingly called Ruisseau de Coupe-Gorge: essentially, cut-throat creek). The tower on the motte overlooked the whole area, and when the brush and forest was cut down around it, as it was in the eleventh century, the viewshed would have been spectacular. The Motte d’Olivet has long been considered a seigneurial residence, but its location, and the history of the man who built it, suggest a far less lofty purpose.

Subscribe to our quarterly newsletter

Image 1: Plan of the site of the Motte d’Olivet. Pighill Archaeological Illustrations redrawn from Decaëns 1981, published in Weikert 2020.

The site was excavated by Joseph Decaëns and published in 1981, though lingering questions remain about the castle and its builder. The elusive Erneis Taissan built the motte in the 1040s-50s during a period of conflict with his older brother Raoul. The Taissons come to greater prominence in Normandy in the twelfth and thirteenth centuries along Raoul’s line; Ralph Taisson, for example, was King John’s seneschal in Normandy at the turn of the thirteenth century. But in this earlier period, the family is more difficult to uncover, and the remains of the Motte d’Olivet are some of the only physical presence we have of them from this time. Decaëns even described Raoul as ‘un personnage très important mais assez énigmatique’ (a very important, but very enigmatic person)!

Seeking evidence of the brothers and their history is an exercise of charters, patience and this castle. Decaëns ascribed the tension between the brothers to each receiving portions of their father’s lands after his death, and Norman charters indicate some expression of this frustration through the brothers’ conflicting patronage of local monasteries. For example, the elder Raoul founded the abbey at Fontenay (St-Étienne de Fontenay, on the Orne north of Grimbosq) in 1050, and its foundation charter, confirmed by William the Conqueror, lists properties Raoul gave to the abbey, all to the east of the Orne. Erneis – who patronised Fontenay but may have preferred the abbey at Fontenelle – held estates mostly to the west of Raoul’s. Grimbosq and Cesny(-Bois-Halbout) are but two of these, with his descendants’ title even named for them. The lines drawn between the properties of these two brothers run straight through the forest where Erneis built his Motte.

Regardless of the cause of the tension, the Motte is the most obvious indication of the brothers’ strife, which visibly plays out the Norman landscape. The Motte directly overlooks the boundaries and roads between Grimbosq – Erneis’ land – and Mutrécy – Raoul’s land – with a clear sightline to the valley to the north, and a ridge to its east leading to Mutrécy. With this in mind, alongside the size of the castle and particularly its distance and isolation from any settlement, the Motte looks less like a seigneurial castle and more like an outpost, a short-lived watchtower to keep an eye on one’s pesky brother. It’s deeply unlikely this motte was Erneis’ main residence, but instead a place for his men to watch the boundaries of his land.

The northern enclosure holds a large aisled building, possibly two-storeyed, and additional stone rooms or buildings which have been interpreted as a sort of a gatehouse providing access to the motte, and a small separate kitchen. The apsidal room was previously interpreted as a chapel but this has recently been rejected by me on varying grounds (including location, orientation and charter evidence), which further indicates this place as less an elite residence and more an outpost. However, the state of the physical remains makes it unclear how to interpret not only the décor but quite simply the form and use of these buildings. The north bailey would probably have housed Erneis when he was there. But if that was this bailey’s primary intention, it would have only occasionally seen habitation, and more frequently seen the men on the watch accessing the motte via the gatehouse. The intention of this castle wasn’t in residency, but in the duties it performed for Erneis, in the watching and waiting done by his men.

The castle’s activity would have been focused in the south bailey. The south enclosure, which held a stable and forge, would have hosted a number of people and animals, and alive with the sights, sounds and smells of a working yard – hot iron and manure, the hammer singing against the anvil. It would have been a site of activity at the castle, a place for the retinue who staffed this border outpost. Game pieces found in excavation mean men entertaining themselves, or perhaps simply passing the time, the way you’d play cards in an airport. As Susan Reynolds and many others have pointed out across the middle ages, military men of a sort gathered together to wait and watch would have probably had some training or practice to attend to themselves: we can envision the south enclosure for this.

Wace tells us that the sons of the two men, Robert fitzErneis and Raoul (II) Taisson, both died at Hastings fighting with Duke William, and the rift between their two families was only repaired at this point. Erneis and Raoul (I) were probably already deceased and, to wit, the Motte was no longer in use by the FitzErneis line. Neither the Motte d’Olivet nor the warring brothers have been further investigated since the site’s excavation in 1981, and new questions about the place and its people can bring different views about what was once considered an elite house. What’s left of the brothers’ rift is just the landscape of this ruined castle, a lonely enclosure in an isolated place, high above the flourishing green forest, a lesson reminding us that castles have much to say about all the people who were once there.

Subscribe to our quarterly newsletter

Katherine Weikert’s new book, Authority, Gender and Space in the Anglo-Norman World, 900-1200, is available from Boydell & Brewer at http://boybrew.co/2YyHx2m. Use the special discount code BB870 for 40% off and free international shipping!

Grimbosq Forest is a part of the city of Caen. It is open to the public and filled with walking and mountain cycling routes, and sites such as an arboretum, a pet cemetery, and the Motte d’Olivet. The Motte is on the yellow walking route, and is unstaffed thought signage gives information about the site. There is free parking, and the forest is also on bus route 34 from Caen. More information can be found at https://caen.fr/annuaire-equipement/foret-de-grimbosq (French) or https://www.calvados-tourisme.co.uk/offer/la-motte-castrale-dolivet/ (English).