Jim Brightman of Solstice Archaeology, dig director of the Richmond Castle excavation, outlines what the next three weeks of excavations of Richmond Castle to mark the 950th anniversary of its founding. The excavation is being co-funded by the Castle Studies Trust along with Richmond and District Civic Society and Richmond District Council.

By way of an introduction to the Richmond 950 community excavation, I’m going to start with a bit of a personal reminiscence. I am a former pupil at Richmond School, and in the dim and distant past when I was in in Lower School (the old Grammar School building), the first topic covered in history lessons was the medieval period. I’d already been fascinated by the past through primary school, and I was ready for it to be my favourite class. I wasn’t disappointed. On a seasonably warm autumn afternoon, we all trooped up the hill for our first site visit: Richmond Castle.

Subscribe to our quarterly newsletter

Many, many years later, having studied archaeology at university and spent my early career in and around the Peak District, I moved back home in 2012. The first time I walked back into town, I vividly remember thinking “was the Castle always that big?!”. Then as now, and as in the centuries preceding, the keep towers over the marketplace, easily the most prominent building in the town’s skyline. Indeed, I was so taken with this icon of my childhood love of history, that the outline of the Castle now features on my company’s stationery!

With the 950th anniversary of the Castle’s original founding rapidly approaching, I was overjoyed at the opportunity to run a volunteer archaeology excavation as part of the wider celebrations being held in the town through the course of 2021. Having been fortunate enough to be involved in a lot of community archaeology projects through the course of my career, it felt like a real homecoming.

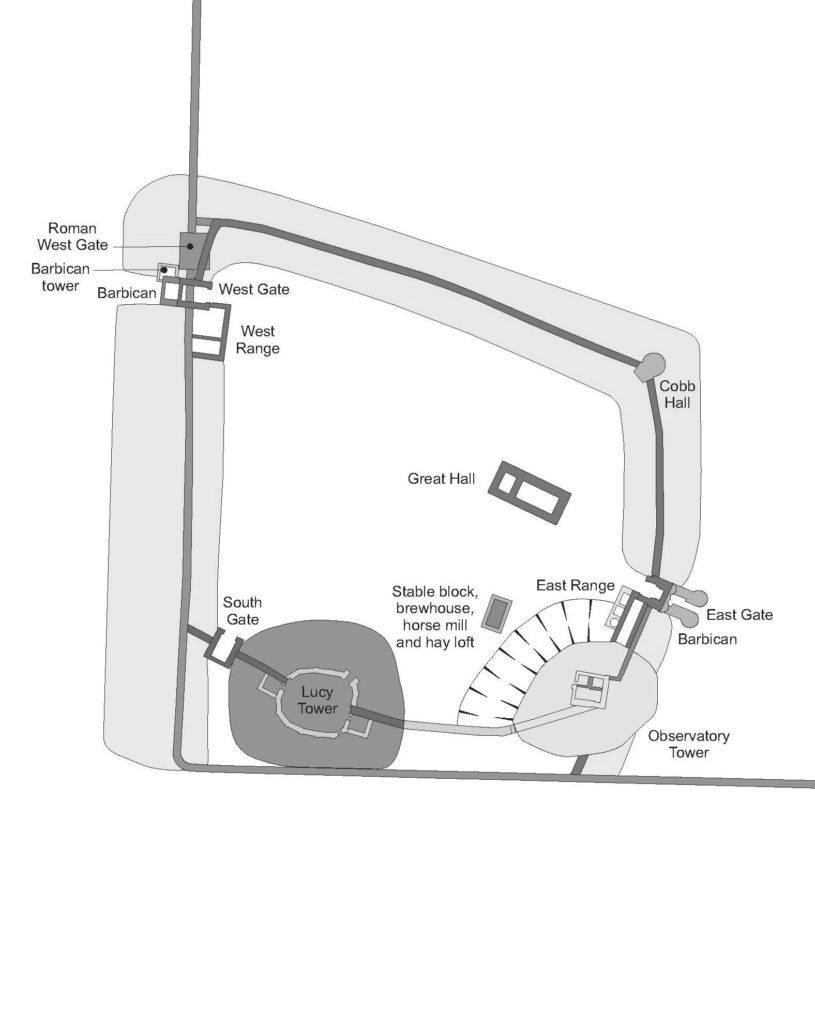

As we started developing the project, it became clear that there was a wealth of places within the Castle where targeted excavation had the potential to shed light on parts of its story that have remained hidden. Geophysical survey in recent years has revealed whole complexes of possible walls and structures beneath the grassy sward of the bailey, and Richmond 950 is the first time that they will see the light of day for many, many centuries.

The volunteer archaeology project was made a reality by the kind support of several funders, all of whom believed in the vision of engaging local people directly with the tangible past in such a beautiful and historic setting. We are very grateful to the Castle Studies Trust, Richmond and District Civic Society and Richmondshire District Council for their huge generosity and support – I feel strongly we will repay your trust with a fantastic project!

As I write this on the eve of the project starting, we are almost fully booked in terms of volunteer places—a real testament to the interest in archaeology in and around Richmond. That said, if you are reading this and getting the itch to try your hand at archaeology, then there are still a few places available on our Eventbrite link; no experience is required and everything you need to unlock your inner Indiana Jones is provided! Even if you are just interested in finding out more, then the Castle is still open to visitors through the next three weeks while we are digging, and we would be delighted to talk you through the unfolding story of the archaeology.

See you in the Castle!