Buildings archaeologist, Neil Ludlow, gives an update of the work that has been done since the Trust funded two projects at Pembroke Castle.

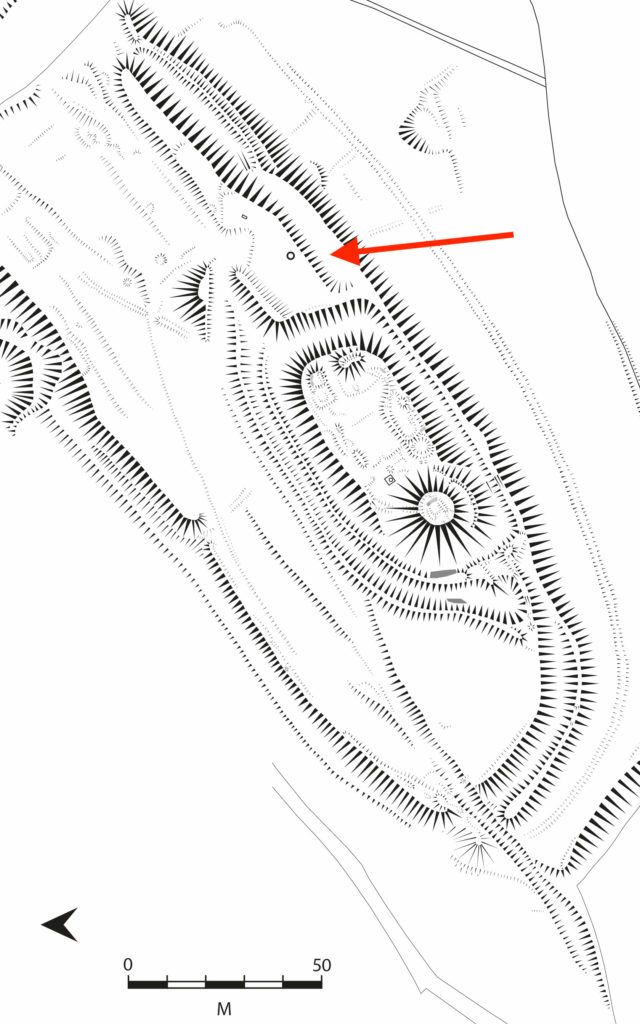

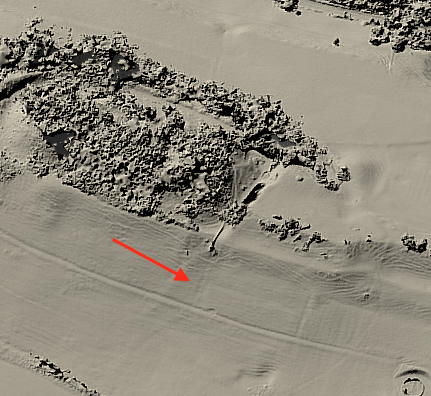

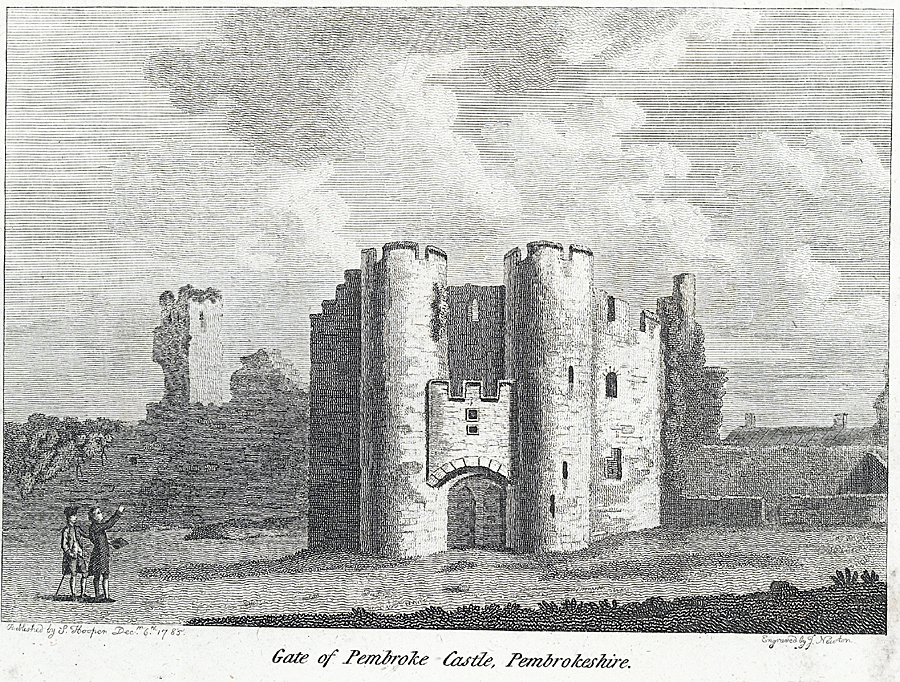

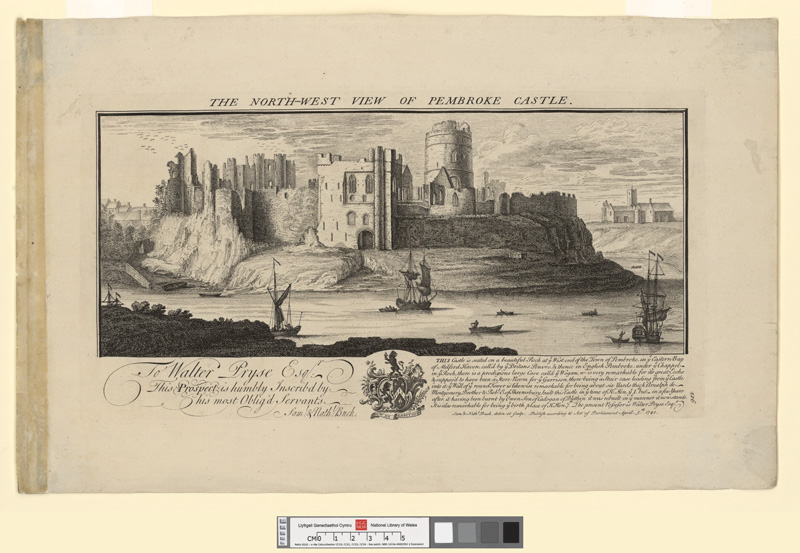

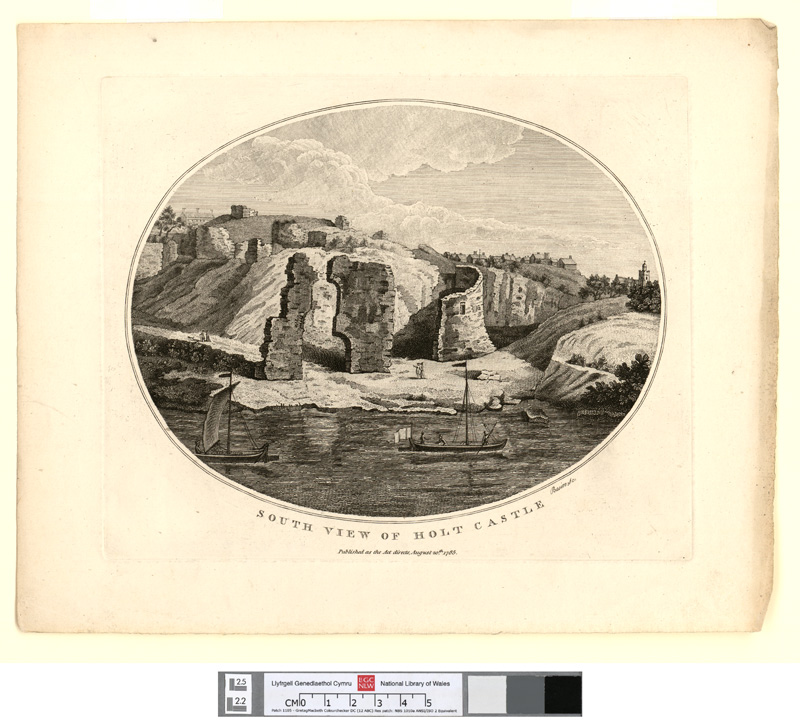

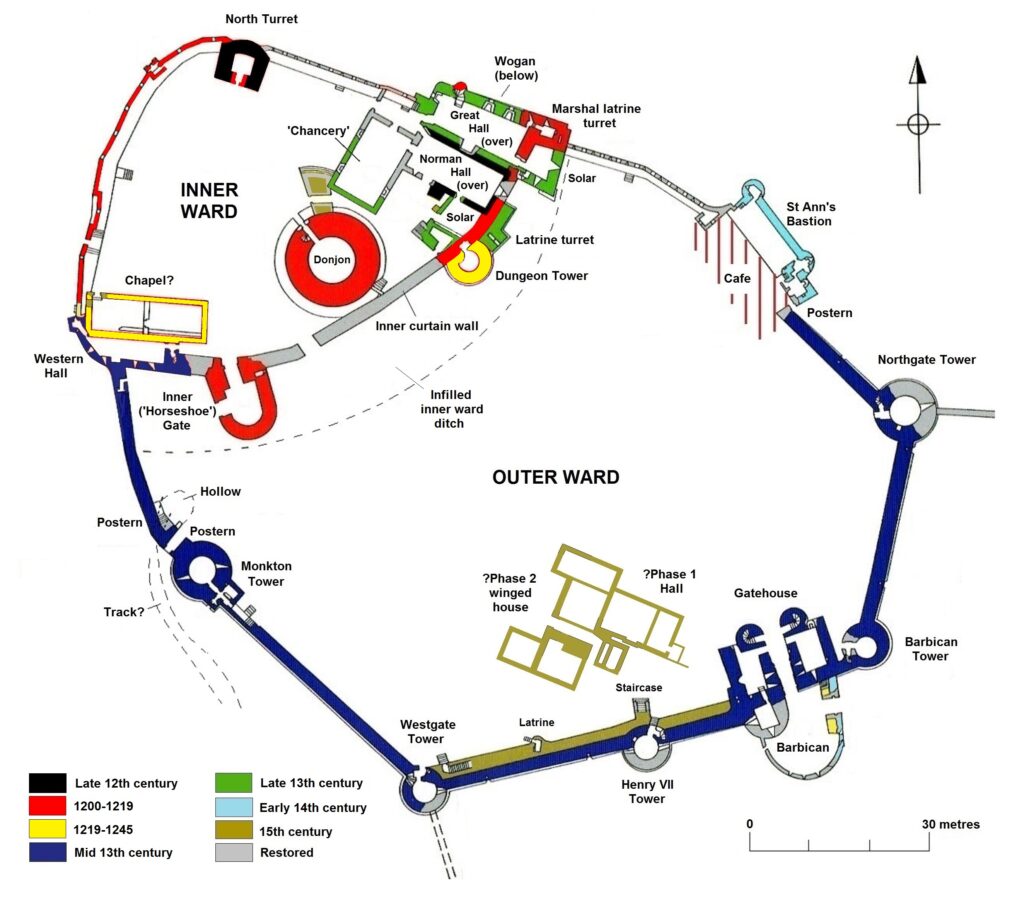

Two CST-funded projects, in 2016 and 2018, looked at a late-medieval building complex in the outer ward at Pembroke Castle (Day and Ludlow 2016; Meek and Ludlow 2019). All above-ground remains of the buildings have gone, but vestiges of walling are marked here on a plan from 1787, while a drawing from 1802 appears to show a surviving doorway. The buildings were part-excavated in the 1930s, but sadly without record. However, the presence of walls, floors and stairs was noted, and a cess-pit from which was retrieved a Limoges-enamelled bronze fitting of late thirteenth/early fourteenth-century date. The wall-lines show as strong parchmarks in dry summers (see Fig. 1).

Subscribe to our quarterly newsletter

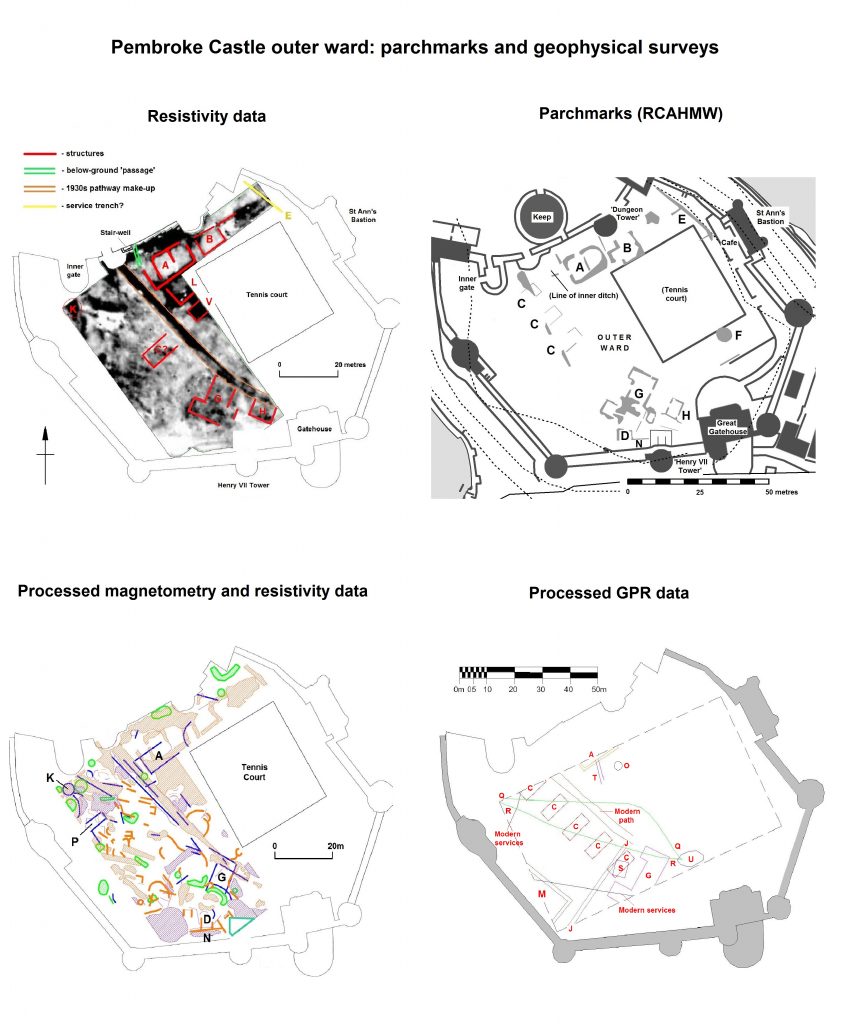

The spacious outer ward was added to Pembroke Castle in the 1240s-50s, and appears to have been an entirely new enclosure. It was not ditched, the limestone bedrock instead being levelled as a platform to receive the curtain walls. And a flanking tower, the so-called ‘Dungeon Tower’, had been built against the inner curtain only 20 years previously, implying that it was still a forward line of defence. Moreover, it subsumed part of the town as at Swansea (Glam.) and Ludlow (Shrops.). Geophysics by Dyfed Archaeology in 2016 suggested it was largely an empty space, perhaps intended for ‘civil’ assembly, military gatherings, pageantry/display or leisure – or perhaps all four. By the early fourteenth century, it appears to have contained a garden and it may always have been perceived as ‘gentrified’ space, rather than seeing the kind of purely functional use that is normally ascribed to outer enclosures (Ludlow 2017).

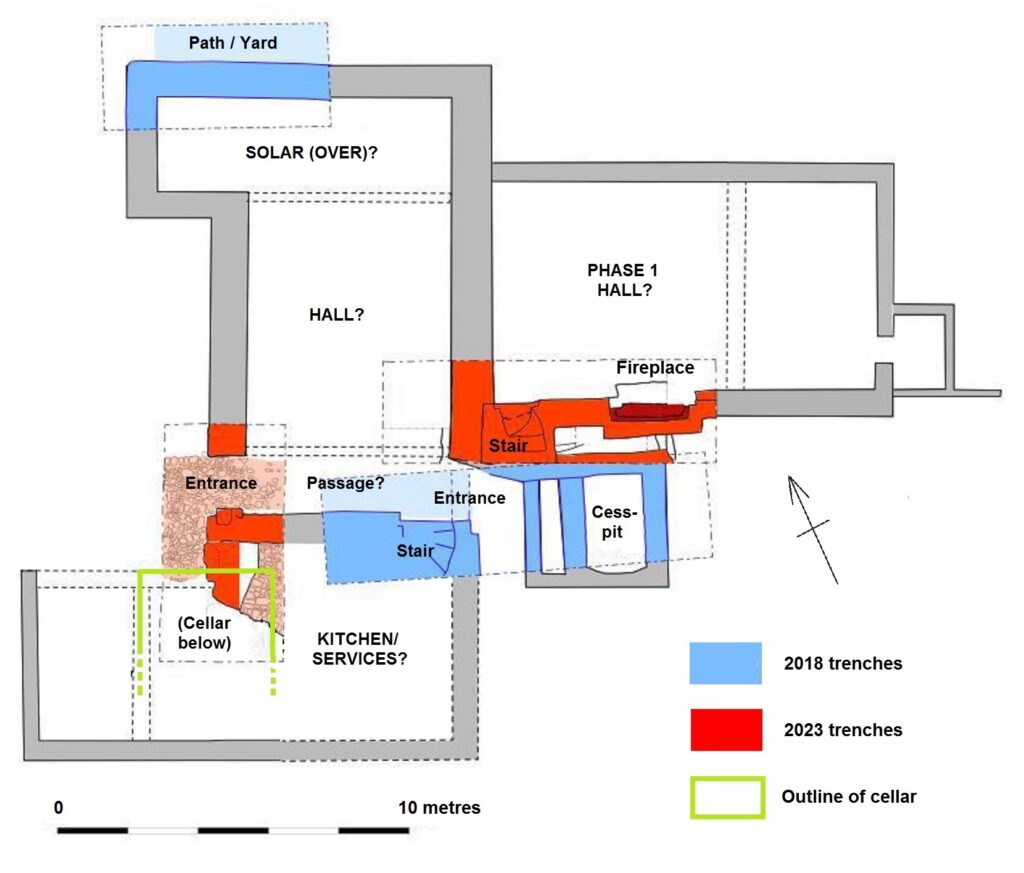

So the complex, which was clearly substantial, was interpreted as high-status and residential: taken along with the parchmark evidence, the geophysics appeared to indicate a substantial, winged hall-house, with a possible yard to the southeast conjoined with a further, smaller building. Two trenches were excavated across the winged house in 2018, by Dyfed Archaeology, revealing walling, a helical mural stair, and the cess-pit exposed in the 1930s (Fig. 2). The excavated area was limited and the full layout of the complex not revealed. Neither was close dating evidence forthcoming.

Two more trenches were dug in 2023, again by Dyfed Archaeology but this time funded by the Pembroke Castle Trust (Poucher 2025). They produced a couple of big surprises. Firstly, a cellar was revealed beneath the southern wing of the hall-house. And what had been interpreted as an open yard, to the southeast, was revealed to be another roofed building, with a lateral fireplace in its south wall (Fig. 2). The base of a further mural stair was exposed in the same wall. The physical relationships showed that this building pre-dated the winged hall-house, but close dating evidence was again slight.

While only four small trenches have been dug, and the site is still very little understood, we can perhaps propose a conjectured sequence. Its scale and location show the house to have been an elite structure from the first. On current evidence, it appears to have begun as a large, free-standing hall, with an attached, storeyed unit at its southwest end overlying a barrel-vaulted cellar; the latter is of a regional form similar to late-medieval cellars that still survive below properties in Pembroke town. This end unit was subsequently replaced with, or adapted into, a winged house that was apparently self-contained: it appears to have comprised a central space (another hall?), associated with the cess-pit and flanked by storeyed wings; the upper floor of the southern wing was accessed via a helical stair.

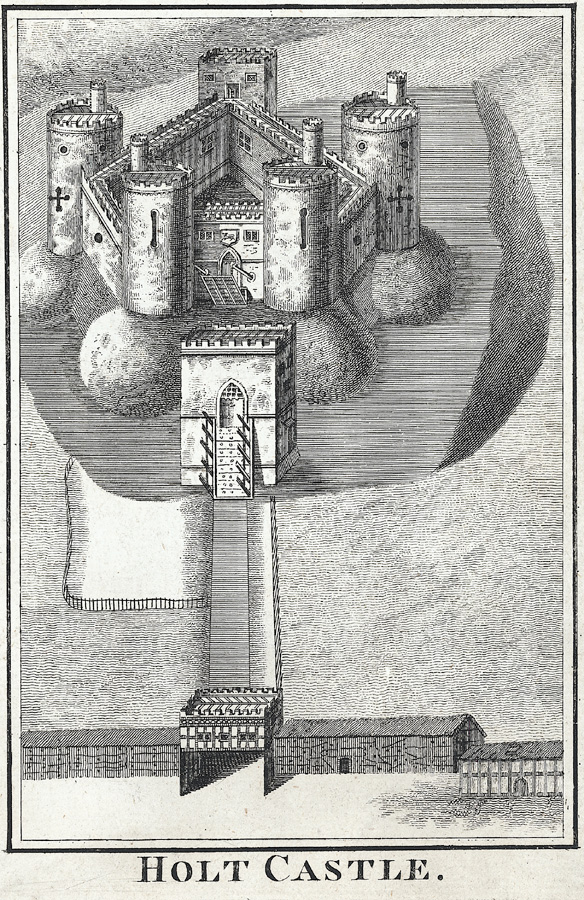

Comparison with similar buildings, and the sparse dating evidence, suggests both phases are fifteenth-century. By this time, the domestic buildings in the inner ward had a history of neglect, coupled with an increasing burden of administrative and penal machinery. The outer bailey was both quieter and emptier, and had perhaps always seen ‘elite’ forms of use, with at least one garden (later two); understandably, it might have been preferred for seigneurial residence. A similar development occurred in another caput castle, at Montgomery, where a mansion house was built in the outer enclosure during the 1530s.

Subscribe to our quarterly newsletter

And the Pembroke house appears not to have sat in isolation. The south curtain wall has, at some period, been doubled in thickness with over two metres of masonry applied to its internal face (Fig. 3). This has long been regarded as a Civil War measure against artillery (see King 1978, 120), but an earth fill was normally chosen for this purpose, while the thin-walled mural passage lies on the exposed external face. I suggest this thickening belongs instead to the fifteenth century, to create a broad ‘promenade’ at parapet level. The use of parapets as promenades has been suggested at a number of castles, from the twelfth century onwards: they provided a viewpoint from which a lord could show off his domain to distinguished guests, while offering scope for high-status recreational use – particularly by women. The Pembroke parapet is approached by two staircases in the thickened section, both of a somewhat ‘processional’ nature. One, a mural stair, is long and straight, while the second wraps around the Henry VII Tower as a double flight of persuasively late-medieval form, and was clearly designed to be seen; it is not obviously military (Figs. 1 and 3). Lying immediately south of the house, it is accompanied by a second ornamental feature – a projecting porch, leading to a latrine within the wall-thickening. This porch, like the thickening, has traditionally been assigned to the Civil War period (King 1978, 94 and n. 75), but in overall form it is not unlike the corbelled oriels seen in later fifteenth-century domestic work (Figs. 1 and 3). Though substantially restored, all these features respect surviving physical evidence; together with a second garden mentioned in a source from 1481-2, they appear to represent a prestige suite of ‘eye-catchers’, clustered around and associated with the hall-house. It is likely, too, that use of the latrine itself was restricted by status and/or gender. The infilling of the inner ward ditch may belong to the same period, to create more seigneurial space.

Three candidates had the resources to build on this scale. It is possible that the Phase 1 hall was built by Humphrey Duke of Gloucester, earl of Pembroke 1413-47, for his personal use. His political influence was in decline by 1441, and he may have intended to use Pembroke as a regular residence, far from his powerful opponents: he appears to have already built a smaller hunting-lodge for himself, just over the river from the castle at Monkton. If so, it is possible that the Phase 2 winged house was added by Jasper Tudor, soon after he acquired the earldom in 1452, in anticipation of occasional visits and to announce his ‘arrival’ among the leading aristocracy. It might not, however, allow enough time for the promenade to be built: after 1454, and until 1461, the Wars of the Roses forced him into more-or-less permanent residence at Pembroke, but in an environment that may militate against such overtly domestic work. Jasper seems moreover to have rarely visited Pembroke after the war, when he concentrated on his favoured castles at Sudeley and Thornbury in Gloucestershire. It may then be that the winged house and promenade were added by the Yorkist leader William Herbert the elder, who held Jasper’s forfeit lands between 1461 and 1469. His work at Raglan in Monmouthshire, where the castle was transformed into a magnificent palace, shows him to have been an ambitious builder.

Subscribe to our quarterly newsletter

References

Day, A. and Ludlow, N., 2016 ‘Pembroke Castle Geophysical Survey 2016’ (report by Dyfed Archaeological Trust for the Castle Studies Trust: see –

http:/castlestudiestrust.org/docs/Pembroke_Castle_Geophysical%20_Survey_FINAL.pdf).

King, D. J. C., 1978 ‘Pembroke Castle’, Archaeologia Cambrensis 127, 75-121.

Ludlow, N., 2017 ’Medieval Britain and Ireland, Fieldwork Highlights in 2016: Pembroke Castle outer ward – gentrified space and Tudor Mansion?’, Medieval Archaeology 61/2, 428-35.

Ludlow, N., forthcoming ‘Two baronial castles in Pembrokeshire: Picton and Pembroke’, Journ. British Archaeological Association 178.

Meek, J. and Ludlow, N., 2019 ‘Pembroke Castle: archaeological evaluation, 2018’ (report by Dyfed Archaeological Trust for the Castle Studies Trust: see – http://www.castlestudiestrust.org/docs/Pembroke_Castle_Evaluation_2018_FINAL.pdf.

Poucher, P., 2025 ‘Pembroke Castle: archaeological evaluation, 2023’ (report by Heneb – Dyfed Archaeology, report no. 2023-33).