In an article that first appeared in Current Archaeology issue 360 (March 2020) Duncan Wright and Samuel Bromage discuss how the two research projects which they undertook at Laughton-en-le Morthen, with CST’s funds, has shown how the siting of castles was influenced by the older patterns of high-status activity in South Yorkshire.

Castles are perhaps the most iconic buildings of the medieval period, which for many are synonymous with feudal warfare and conflict. In spite of this popular perception, the idea that castles were mainly built for military purposes has been questioned for some time, and archaeologists now point to a number of reasons for their construction. In England, even fortifications thrown up in the wake of the Norman invasion are no longer seen purely as tools of martial conquest.

Subscribe to our quarterly newsletter

Instead, it is increasingly clear that earlier patterns of aristocratic life were important, and that the manorial residences of the Anglo-Saxon nobility in particular were chosen for the siting of early castles. Such targeting should not come as a surprise—the Conquest is understood as an exercise in elite regime change, which saw the near wholesale replacement of existing lords with incoming Norman tenants-in-chief. Yet, the way in which this transformation physically manifested is poorly understood. Few relevant sites have been subject to excavation, and where archaeological intervention has taken place it has often been piecemeal or of limited size. The Landscapes of Lordship project seeks to improve this picture, and recent work at Laughton-en-le-Morthen in South Yorkshire, funded by The Castle Studies Trust, offers a case study of archaeology’s potential to reveal more about this fundamental aspect of the Conquest.

Anglo Saxon Elements

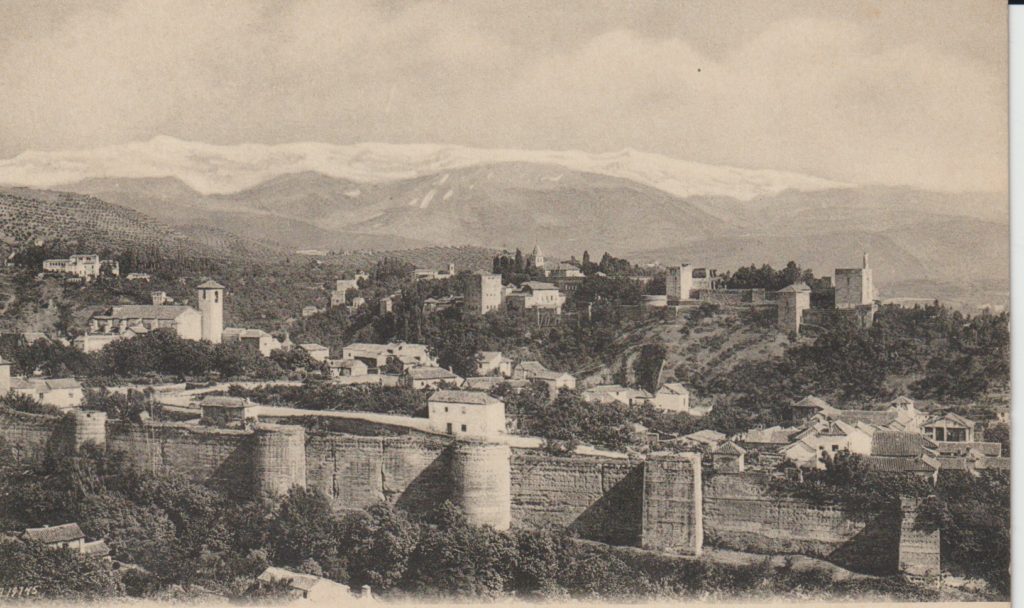

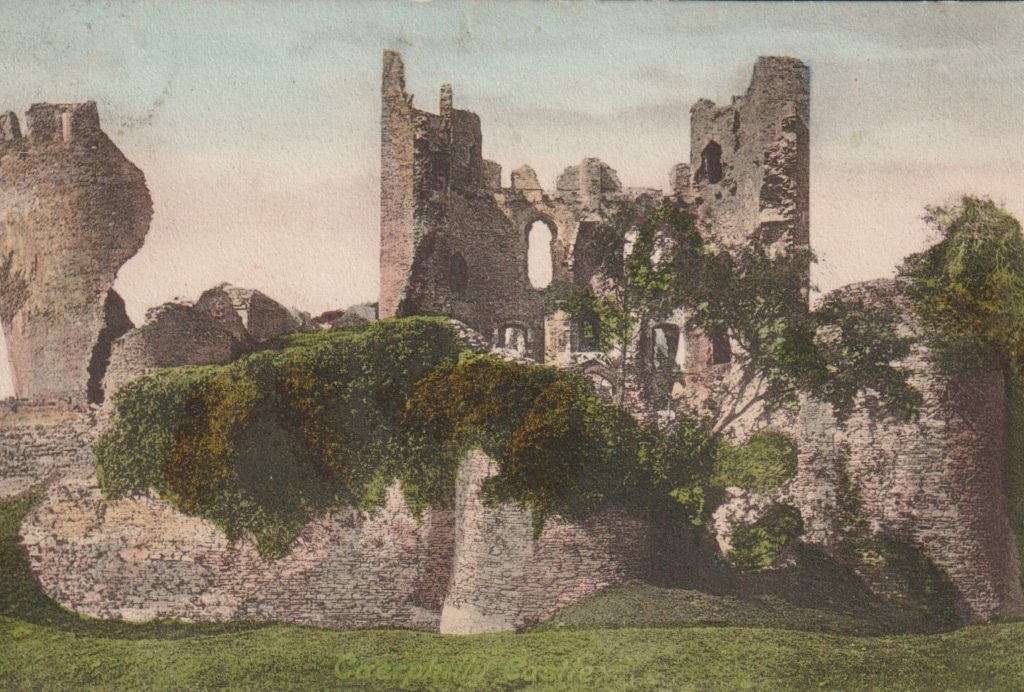

Laughton today is a modestly-sized village in the Rotherham district, perched high on a limestone ridge which offers impressive views, especially westwards towards the Peak District. The historic core of Laughton is focussed around the parish church of All Saints and the adjacent remains of a motte and bailey castle. A visit to the former provides the first hints of Laughton’s early history; an elaborate 10th or 11th-century doorway is located in the church’s north wall, and a similarly-dated grave slab is built into the eastern exterior of the chancel. Inside the church, a triangular-headed opening, a distinctive pre-Conquest form, covers a piscina—a shallow basin used to wash communion vessels. These pieces of stonework indicate the presence of an earlier building at Laughton, decorative fragments of which have been reused in later phases of construction. It is almost certain that this structure too was a church, as stone was almost never used for secular building in early medieval England.

In 2005 archaeological excavations due east of All Saints also found evidence of pre-Conquest activity, in the form of a circular grain-drying kiln. A significant assemblage of 10th—11th-century pottery was recovered from the excavations, highly unusual finds given that South Yorkshire was largely aceramic at this time. Documentary sources help to provide some context for the excavated material and that found in the church. The Domesday Book records that, prior to the Conquest, Earl Edwin of Mercia had an ‘aula’ or hall at Laughton. Edwin was a leading noble, but also a leading protagonist against the Norman regime. Brother-in-law of Harold Godwinson, Edwin, together with his younger brother Morcar, raised an unsuccessful rebellion against William the Conqueror after the Battle of Hastings. Dispossessed of his extensive lands, Edwin was ambushed and killed three years later.

Subscribe to our quarterly newsletter

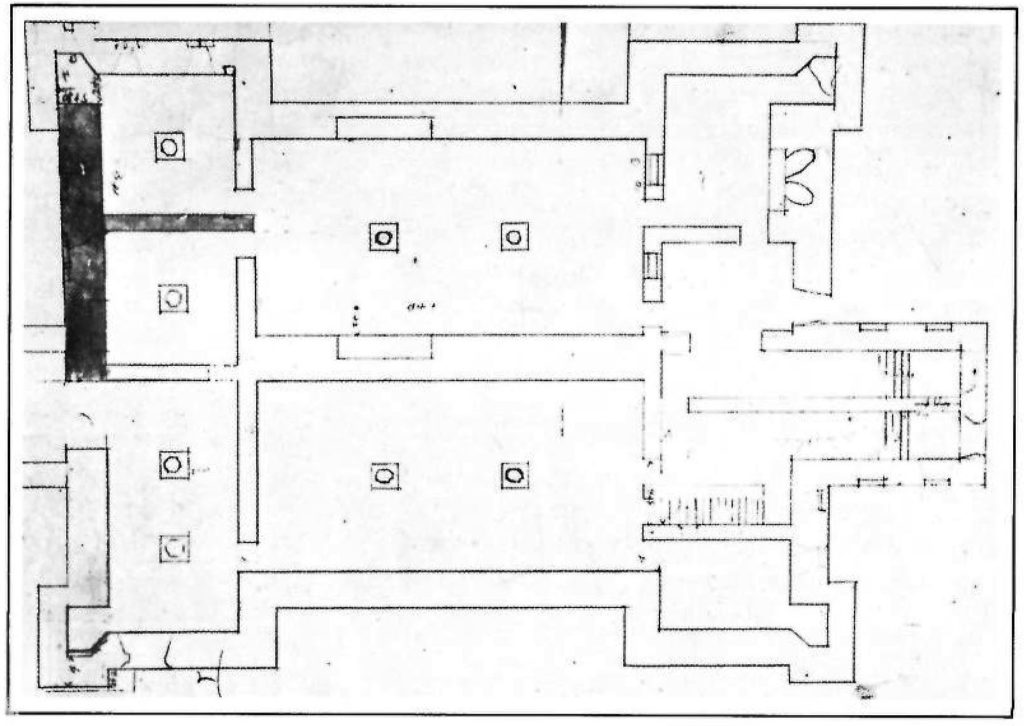

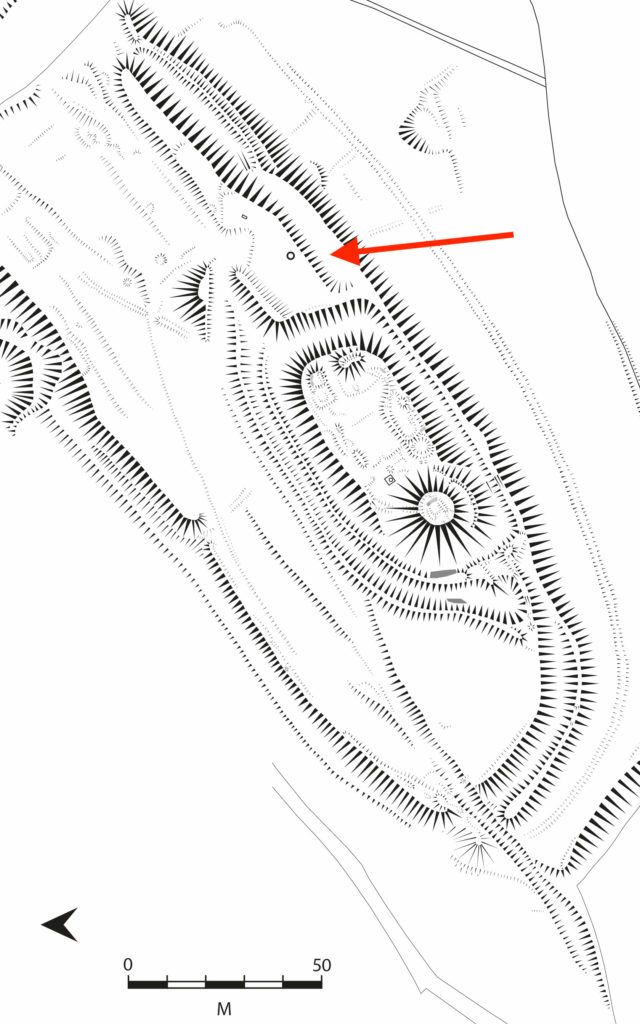

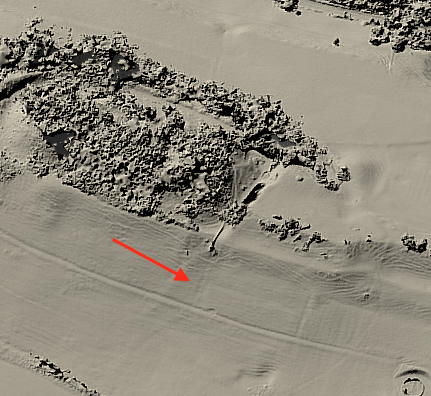

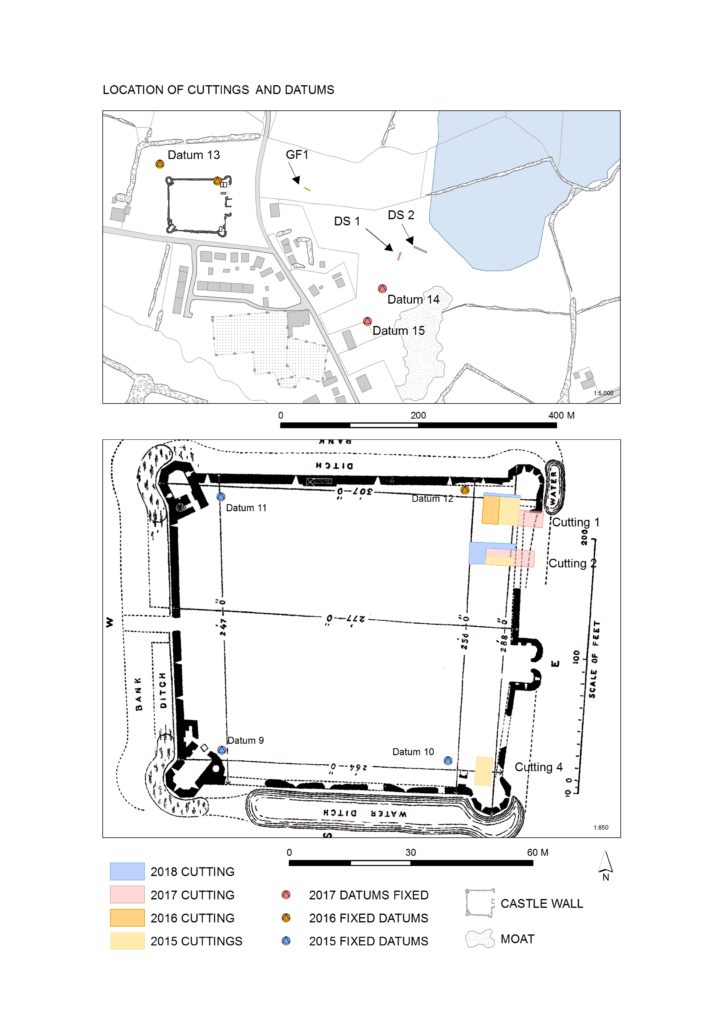

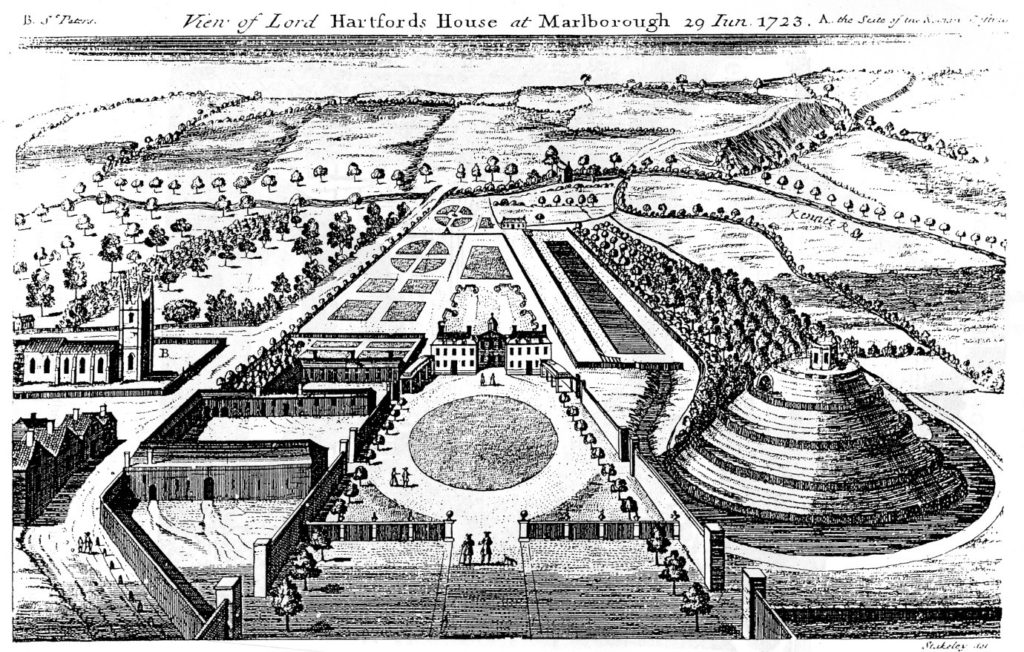

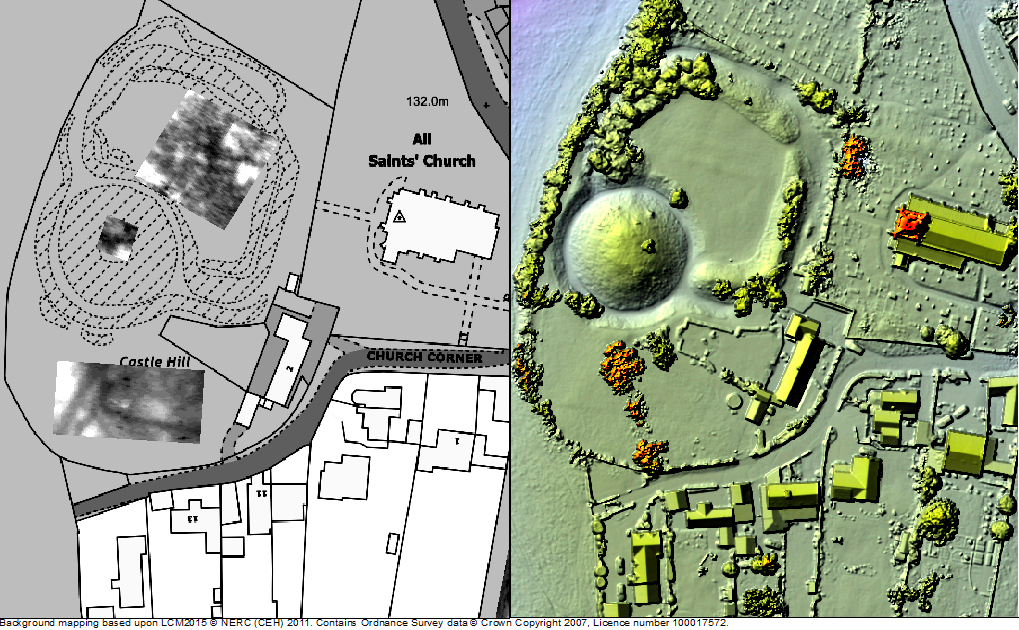

Exactly where Earl Edwin’s hall was located in Laughton has long been a mystery, with the popular belief that it lies under the earthworks of the castle. The Landscapes of Lordship project set out to test this idea, firstly through a scheme of topographic and geophysical survey. A detailed topographic model of the castle and the surrounding parts of the village was made using a drone, and earth resistance survey provided a plan of buried features from the bailey and an area of open ground to the south. The results from the combined techniques exceeded even the expectations of the team, identifying a host of important archaeological features. In the bailey, geophysics picked up a number of anomalies which were also detectable as a low earthwork—the size and shape of which is consistent with buildings, and probably represent the centre of Earl Edwin’s hall complex. To the south of the bailey, ditches seemed to form two sides of an enclosure, one side of which was interrupted by the apparent construction of the motte.

Although the project team were confident that these features were related to Edwin’s estate centre, it was decided that a targeted excavation would be best to confirm this conclusion. A second phase of work, also supported by the Castle Studies Trust, was instigated to ground truth some of these findings, with two trial trenches dug over the ditches to the south of the castle. Excavations uncovered a V-profile ditch with a distinctive narrow base, which would have served to locate a wooden palisade, supporting the premise that this was indeed Edwin’s compound. No datable material was recovered from the ditch but the material inside was notably clean and consistent, indicating that infilling had occurred in a short window or perhaps as a single event. Beyond the enclosed area, another more substantial ditch was found—this feature seemed to project southward from the castle and may be part of an enclosure surround the village, the form of which is preserved in the historic street plan.

Hunting the Hall

The Landscape of Lordship investigations, then, support the idea that Laughton was indeed the site of Earl Edwin’s ‘aula’ and other buildings, which were surrounded on all sides by a ditched enclosure enhanced with a palisade. Edwin and his entourage would have had exclusive use of the elaborate stone church, which topographic evidence demonstrates lay within its own small rectilinear churchyard. Outside of this high-status enclave, the find of a drying kiln suggests that Laughton acted as a point for the collection and processing of agricultural produce, potentially from an extensive area. Indeed, Laughton was the centre of a large territory incorporating several later parishes, the component settlements of which are now most discernible by their ‘Morthen’ place-names.

At some stage, Laughton’s lordly compound was radically transformed—the palisade fence was taken down and the ditches rapidly filled in; in their place was constructed a massive earthwork motte across the western edge of the enclosure. A kidney-shaped bailey incorporated the most important buildings including the hall, but it is impossible to tell without more investigation whether these were maintained or replaced with new structures. Probably around the same time the settlement to the east of castle and church was surrounded by a rectilinear enclosure, effectively forming an extensive outer bailey of the castle. Such arrangements are not uncommon in England but perhaps the most famous is at Pleshey in Essex, where a semi-circular bank and ditch encircles the village to the north of a motte and bailey castle.

While the nature of the archaeological evidence does not provide absolute dates, the most compelling context for the apparently rapid changes visible at Laughton is the protracted conquest and subduing of northern England in the years following the Norman invasion. Once annexed, Laughton and its estate were quickly subsumed into a large territory given to Roger de Busli who established a centre at Tickhill where a sizeable castle was erected. Given that the main seat of authority lay at Tickhill, it is unusual that Laughton too was furnished with a castle and that it continued to act as an administrative focus at least temporarily. The explanation for Laughton’s perpetuated importance undoubtedly lies in its pre-Conquest past. As an important residence of Earl Edwin, a foremost member of the Anglo-Saxon elite, Laughton’s appropriation was clearly an attempt to assume a recognised place of power. Yet, the drastic overhaul of the site also embodies a conspicuous act of conquest, physically destroying the complex of a central opponent to Norman rule. It is possible that the processes of castle construction in itself was its raison d’être, acting as a material ‘seal’ of new authority in the eleventh-century landscape. Indeed, this may help explain the paucity of medieval finds from the excavation—the castle itself having experienced little or no use, as its primary purpose had already been met by its very building.

The work by the Landscapes of Lordship project has provided a unique insight into Laughton’s past, showing the importance of older patterns of high-status activity in shaping the process of castle siting in South Yorkshire. The project team now intend to employ this approach to further sites and regions, allowing a new archaeology of elite residence, conquest, and regime change to be written.

Subscribe to our quarterly newsletter

Duncan W Wright was Senior Lecturer and Programme Leader of Archaeology and Heritage at Bishop Grosseteste University, Lincoln during the project and has recently been appointed Lecturer in Medieval Archaeology at Newcastle University

Samuel Bromage is a PhD researcher at the University of Sheffield. His doctoral thesis investigates the consequences of the Dissolution for urban development in Yorkshire.

Current Archaeology can be found here: https://www.archaeology.co.uk/