In their latest update Drs Paul Pattinson and Esther van Raamsdonk look at how far they have progressed with the transcription and translation of the Seventeenth Century survey of fortifications in southern England, revealing some pleasant surprises that have awaited them.

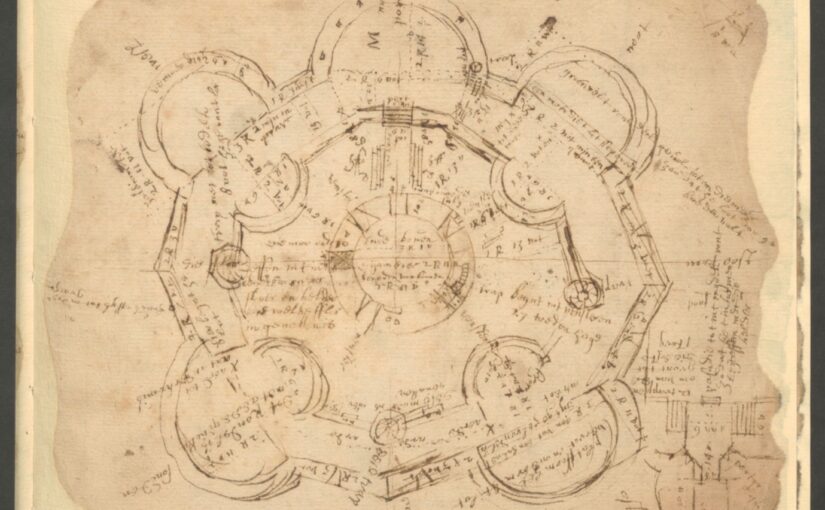

In our last update on Transcribing and Translating SP9/99: A Seventeenth-Century Dutch Survey of 22 English Castles and Fortifications, we concentrated on just that, the challenging process of transcription and translation of a difficult Dutch manuscript that uses unorthodox words (whose meaning is sometimes unknown), a note-like format, and a complete lack of punctuation. That process is now essentially complete, bar a few words that may be technical terms, and about which we are consulting with fortification experts in the Netherlands. However, we can now begin to interpret the manuscript and what it can tell us about the coastal artillery castles and bulwarks along the south-east and south coasts of England in the early seventeenth century.

Subscribe to our quarterly newsletter

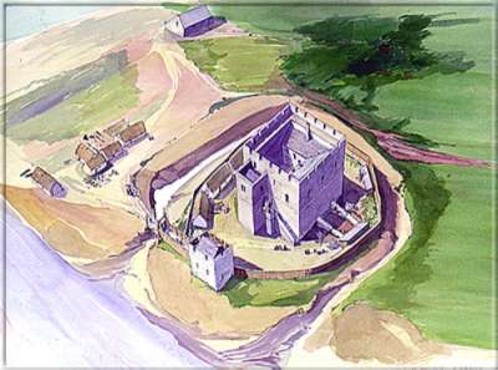

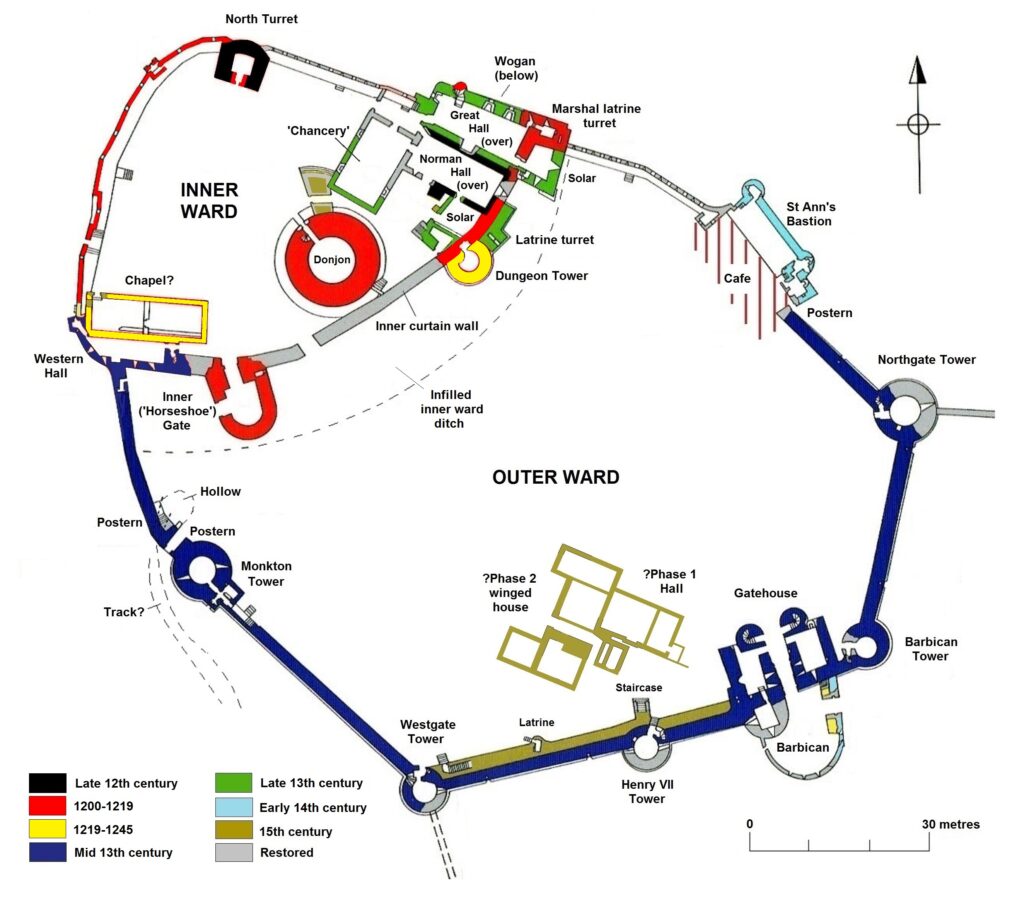

After looking briefly at the whole manuscript of 23 folios (46 pages), we can now say that there are details of at least 29 fortifications, not just 23, and that may not be the final number. In due course we hope to establish a complete list. For the time being, the work for which we were generously grant-aided by the CST focussed on 9 folios covering 6 artillery castles, all of which were built or modified during the early stages of the ‘device’ programme of Henry VIII, between 1539 and 1541. We selected these as a suitable sample of the manuscript because historically they formed a discrete group in the jurisdiction of and under the command of the Lord Warden of the Cinque Ports: they are the castles at Sandown, Deal, Walmer, Dover, Sandgate and Camber.

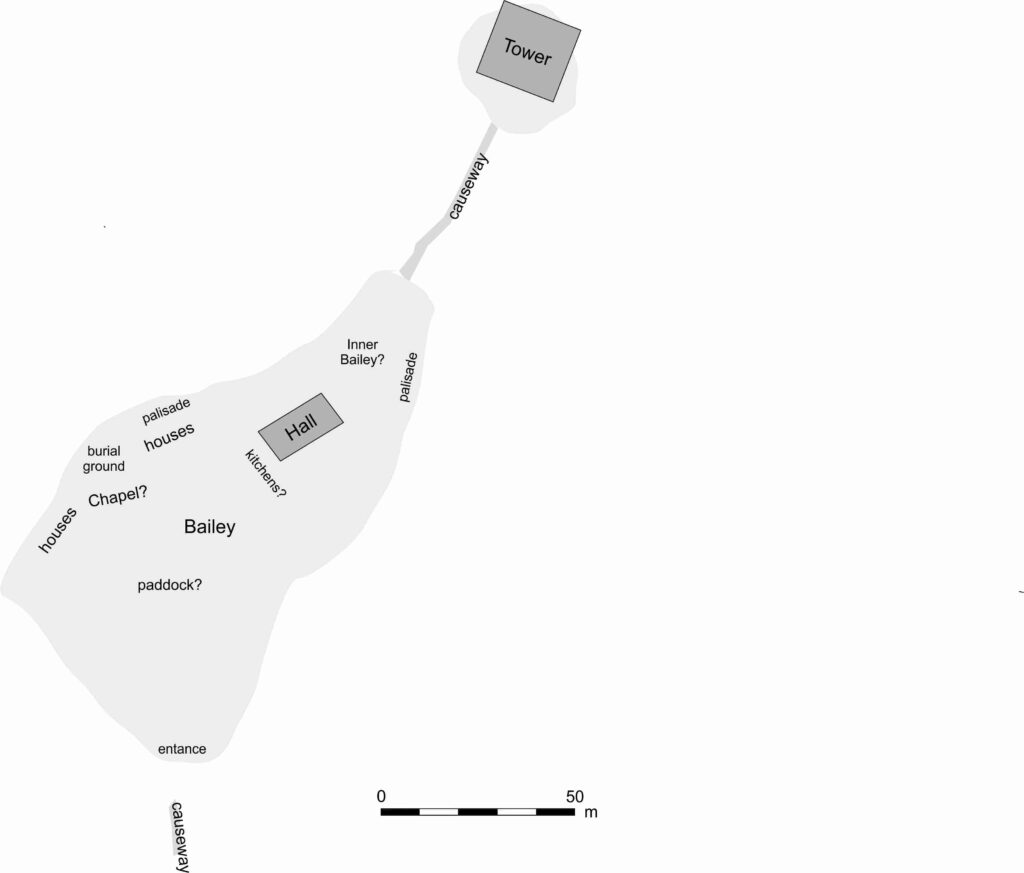

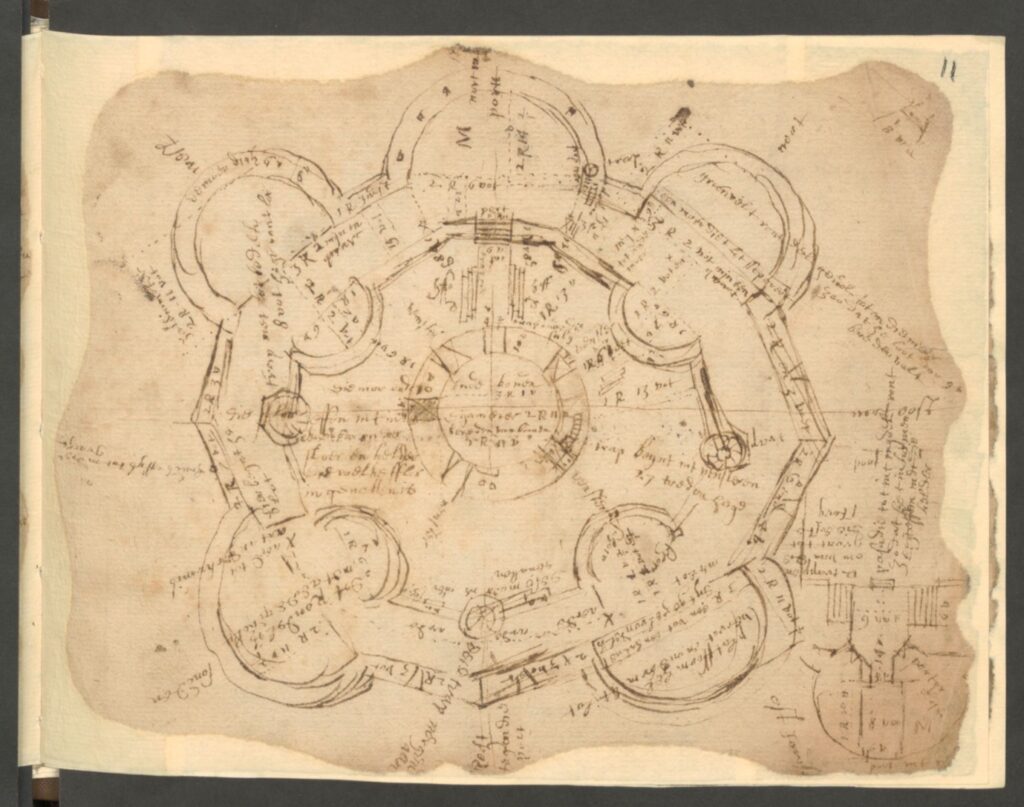

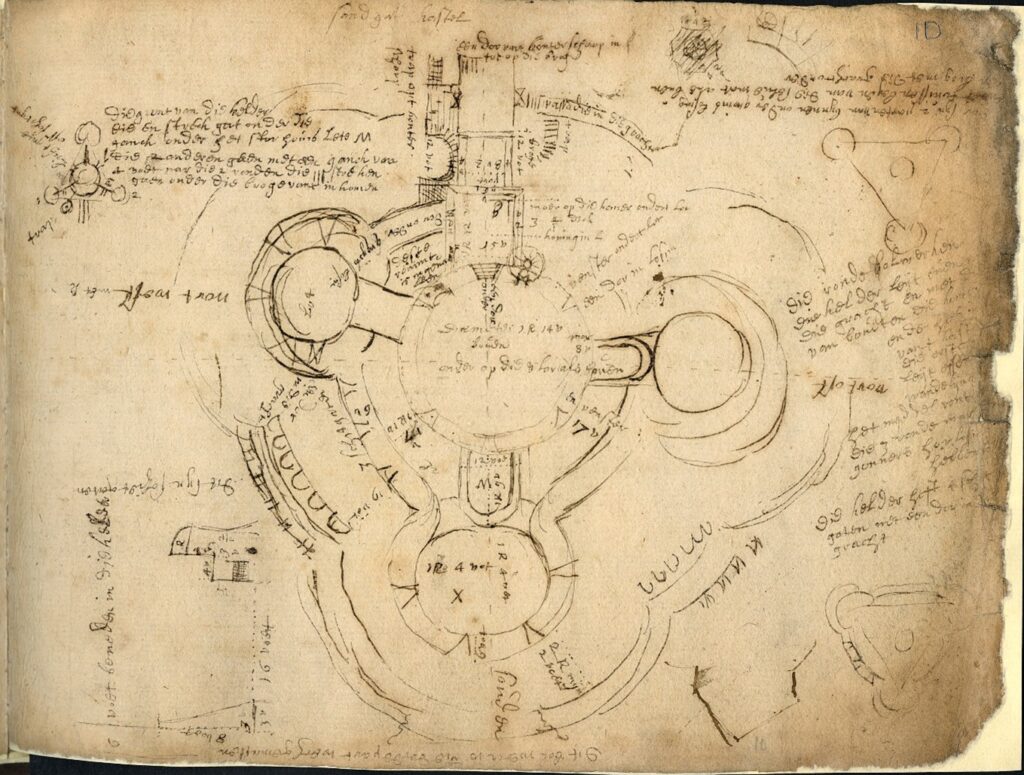

Even though our unknown Dutch engineer was clearly in a hurry with his survey, as we reported last time, his work is accurate. For most sites there is usually a main plan taking up one face of a folio – a detailed and well-proportioned sketch with copious annotations that include measurements and notes on features of interest, sometimes including room use, and often pointing out defects requiring attention. In rare cases a room is named, notably ‘The Queen’s Room’ at Sandgate, a lovely, early reference to a tradition recording Elizabeth I’s stay at the castle in 1572. Sometimes, room functions are specified e.g. the porter’s lodge at Camber, giving valuable insight to the daily workings of a castle.

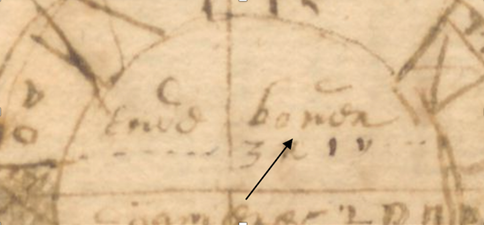

As well as a main drawing, the engineer also made smaller sketch plans and elevations to show details e.g. an elevation of the cupola at the centre of the roof at Deal Castle, noting also its use as both a gunpowder store and a sea mark; or a plan of a double-splayed gun embrasure at Walmer Castle. Typically, the particulars of each site are further noted in a separate block of text taking up another side of a folio, sometimes also incorporating small sketches. This text tends to summarise defects and requirements, so does not provide a full picture of the castle, but rather concentrates on repairs needed and remedies.

However, there is one atypical folio that mentions two known individuals. One is the relatively well-known master gunner at Dover Castle, William Eldred, notable for his authorship of The Gunners Glasse, a treatise on gunnery published in 1646. The other was a Mr Griffiths, secretary to Edward, Lord Zouche, who was Lord Warden of the Cinque Ports between 1615 and 1625. We are presently exploring them both in the State Papers at the National Archives and in other documents at the British Library and we are confident – and excited – that we will be able to tie down the date of the survey to the year.

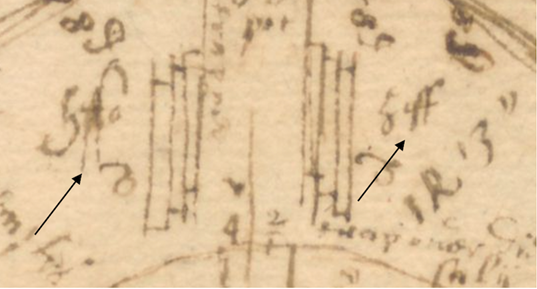

The translation of three other folios for Dover Castle represents a real step forward in understanding that castle during this otherwise hazy period in its history. The manuscript names and provides details of eight mural towers, two gates and three other buildings explored by the engineer, most of which we can relate to those surviving today, possibly the earliest evidence we have for named towers in the castle: a few of the names are previously unknown. There are three sketches of tower plans, which should enable their identification: one is certainly Fitzwilliam Gate. Many of the Dover Castle towers needed significant repairs, for which the engineer estimated costs. The Dover folios also record two forts defending the harbour and anchorage. The first is Moats Bulwark, the battery at the base of the cliff below the castle, just above the beach, and the small angle-bastioned fort guarding the western harbour, Archcliffe Fort.

Only recently, we have begun to look closely at another survey, long thought to be broadly contemporary, carried out in 1623 by the Board of Ordnance at the request of James I and his Privy Council. Our initial work on this, comparing entries for the same sites, suggests that the two surveys may be closely related and we look forward to providing another update here, when we have fully explored that intriguing possibility.