Neil Ludlow and Phil Poucher of DAT look at the results of the investigation at Haverfordwest Castle by Dyfed Archaeological Trust (DAT), as part of a major infrastructure scheme embracing the castle and its setting, has revealed what may be part of the medieval town wall, long thought to have been entirely destroyed.

The remains of the castle still dominate views of the town, particularly from the main eastern approach, crowning a steep bluff overlooking the Western Cleddau river. Founded around 1110 by one Tancard, a Flemish colonist, the castle appears to have begun as a partial ringwork and bailey, perhaps adapted from an Iron Age hillfort. Fortification in stone began under Tancard’s grandson Robert FitzRichard, a decade or so either side of 1200, with the erection of a subrectangular donjon; a curtain wall with at least one round mural tower was later added, possibly by the younger Marshal earls of Pembroke between 1219 and 1245. The castle was transformed into a palatial residence with the addition of an integrated suite of apartments of the highest quality, including hall and chamber-block ranges, and a terraced garden enclosure; they are traditionally attributed to Edward I’s queen Eleanor of Castile who received the castle and lordship two years before her death in 1290. The outer ward was also walled in stone, probably during the early fourteenth century. Although it played no part in the second Civil War of 1648, the castle was partially slighted on Cromwell’s orders and was subsequently used as a gaol, which closed in 1878.

Open to the public since 1970, and housing the town’s museum and County Record Office – but still perhaps an under-valued asset – the castle is now the subject of an enhancement programme to improve access, carry out essential repairs and redevelop the museum. The scheme extends to the castle’s setting, with improved landscaping and restoration of the surrounding burgage-plot boundaries. Preliminary archaeological work includes geophysical survey and test-pit recording.

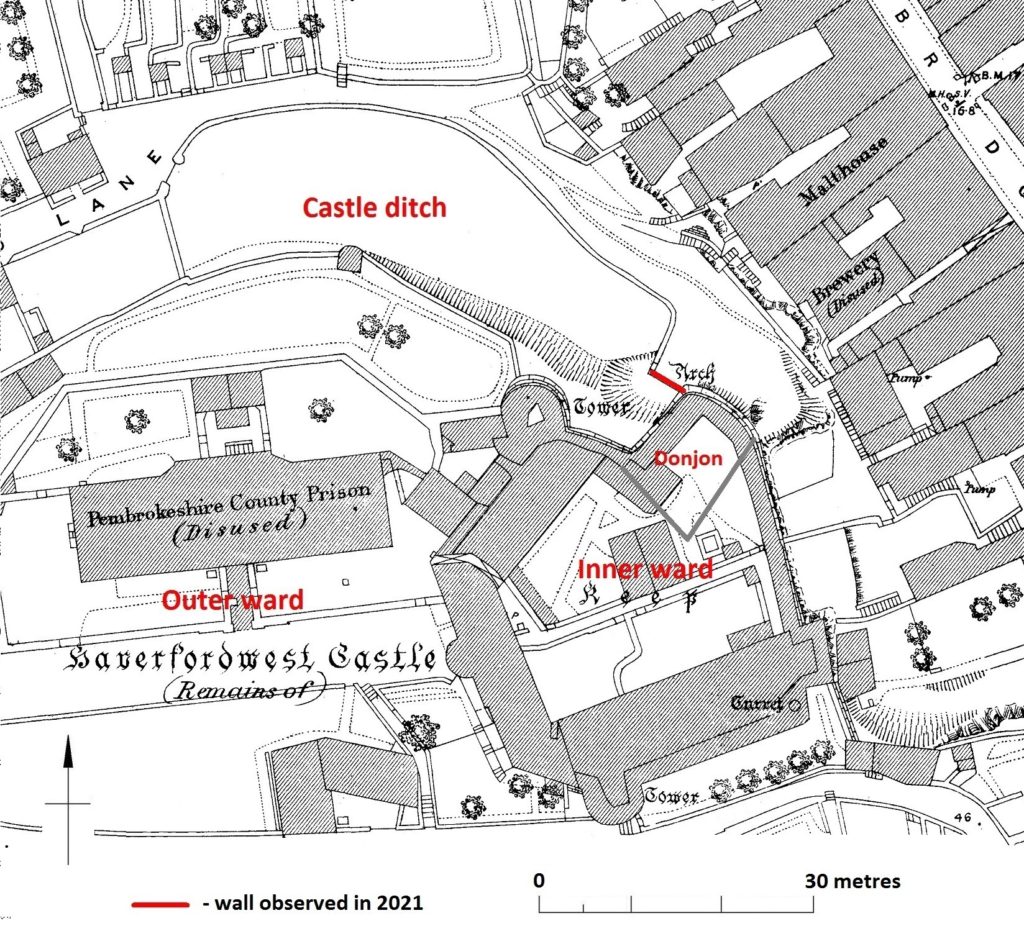

Investigating the castle exterior in early 2021, at the summit of the steep bluff, Andy Shobbrook of DAT came upon a stretch of walling that appears to have evaded previous investigations. Now of no great height, but probably truncated, it is pierced by a wide segmental arch of convincingly medieval form (Fig. 1). Although absent from published plans and descriptions of the castle, it is shown on the large-scale 1:500 map of the town produced by the Ordnance Survey in 1889, on which it is labelled ‘Arch’ in the Gothic script reserved for antiquities (Fig. 3). It lies just within the scheduled area of the castle, corresponding with its boundary, and appears to be in a stable condition.

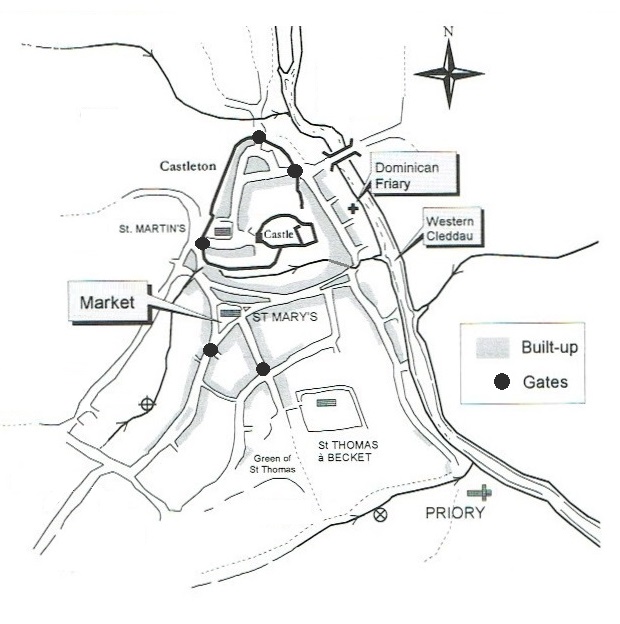

The walling may be part of the medieval town wall rather than the castle defences. The town of Haverfordwest, which is notable for its three medieval parish churches – unique in Wales – was founded soon after the castle and by the close of the Middle Ages had become the de facto county town of Pembrokeshire. Defended by an earthen bank and ditch from an early period, probably before 1200, it was walled in stone after the issue of a murage grant in 1264. The defended area was relatively small, immediately next to the castle and always known as the ‘Castleton’ – while the extensive suburb around the extra-mural marketplace to the south received fortified gateways, they were never connected by any solid barrier (Fig. 2). The town wall had largely disappeared by 1700 and, while the gatehouses survived rather longer, the last were removed at the end of the eighteenth century.

showing the castle and walling (labelled ‘Arch’).

Vestiges of the wall were apparently still detectable in 1900 but all traces were thought to have been lost soon afterwards. Stretches of its former line are marked by property boundaries but its entire course is not precisely known, nor the points at which it connected to the castle defences. The walling discovered in 2021 butts against the donjon at the northeast corner of the castle inner ward, and runs northwest for 5 metres before petering out. The remains of a return at its northwest end correspond with a 90° turn shown on the 1889 map, on which it is shown to then run north-eastwards before turning west to continue along the outer edge of the castle’s northern ditch. But the medieval wall must have deviated from this line at some point, to run northwards to the eastern town gate. The arch is 3 metres wide but was probably always too low – and perhaps too wide – to represent an entry. Its function may simply have been to drain the area immediately to the west, which slopes steeply downhill towards the east and seems to have been a continuation of the castle ditch where it ran out at the crest of the bluff (Fig. 3). Two phases of work within the arch are possible, suggesting it was modified and perhaps narrowed at some point.