In 2024, we awarded Stephen Parry in conjunction with MoLA a grant to carry out some geophysical surveys in the town of Higham Ferrers to find the lost royal castle once there. Stephen explains what happened next and what they found.

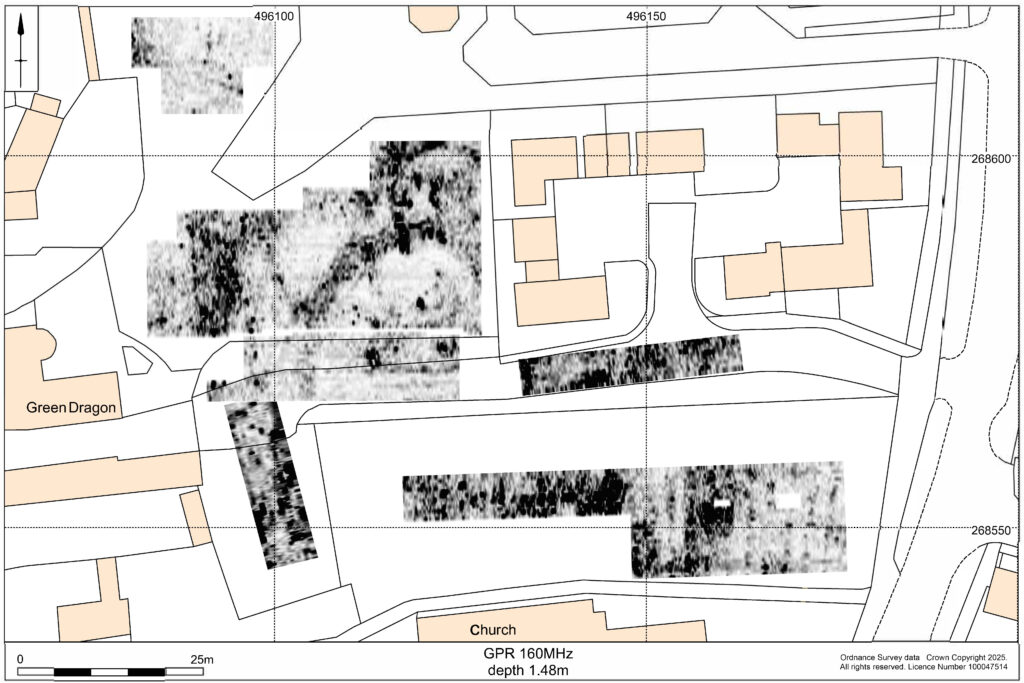

Over a ten-month period during 2024-25, a team of archaeologists used a combination of ground penetrating radar (GPR), magnetometry and earth resistance survey to reveal some of the mysteries of Higham Ferrers Castle, gaining new insights into what this royal castle might have looked like.

Subscribe to our quarterly newsletter

A generous grant from the Castle Studies Trust, supplemented by further grants from East Northamptonshire Council, Higham Ferrers Town Council and Tony & Jennifer Norman and with the support the Higham Ferrers Archaeology and Research Society (HiFARS), enabled archaeologists Stephen Parry (Finham Heritage), John Walford and Graham Arkley (Museum of London Archaeology) to undertake this project.

No remains of the castle survive above ground today so, before this project, our understanding was largely based on historical documentary evidence. This showed that the Castle was, at least from the early fourteenth century, a substantial medieval building with a hall, chapel, tower-house, King’s and Queen’s Chambers, as well as three gatehouses.

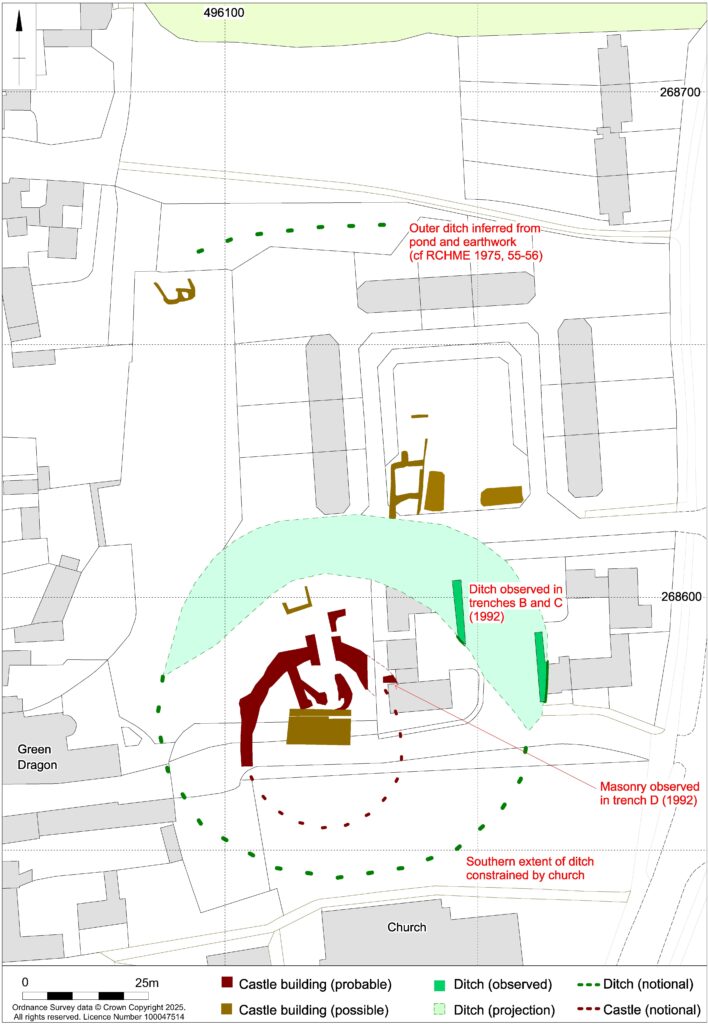

The GPR survey produced the most informative results, showing that the foundations of a curtain wall and other buildings of the inner bailey survive under the garden of the Green Dragon Hotel. Other building remains survive to the north, within the likely extent of the outer bailey.

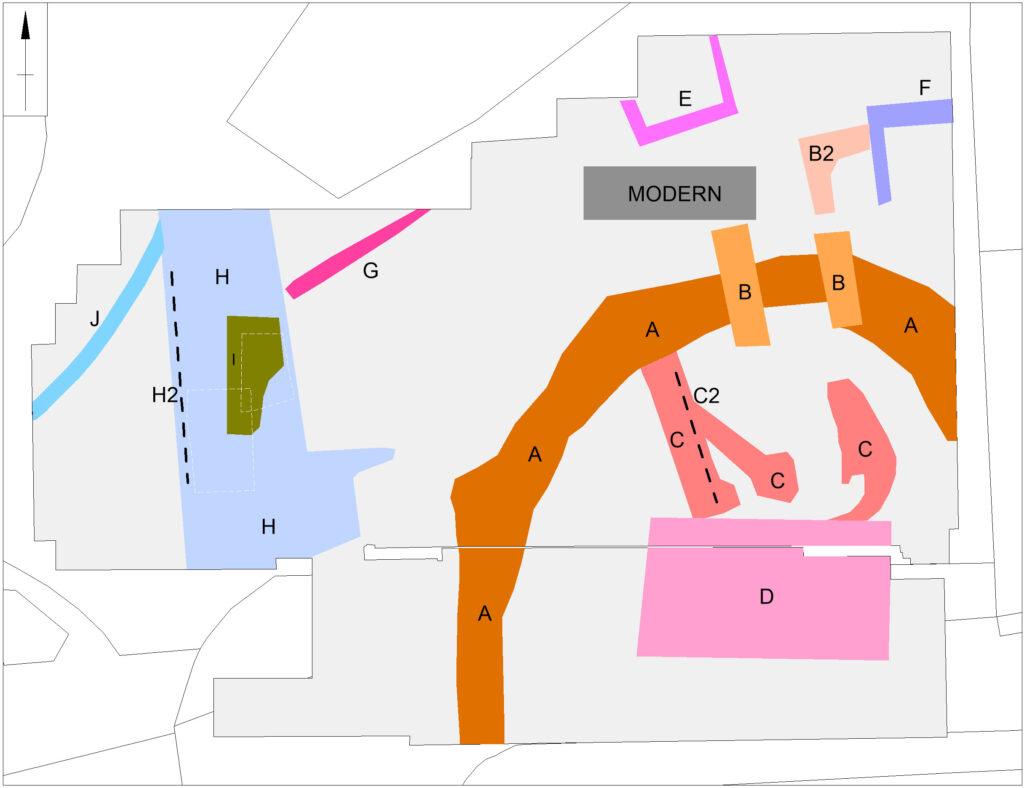

The broad foundation of the curtain wall (structure A in figure 3 appears to be made up of short straight lengths perhaps with slight projections at the angles. It probably enclosed an oval area measuring roughly 29m by 25m across. However, the southern part of its circuit, which must have lain under the churchyard, was not found by the survey and is likely to have been masked, or perhaps even destroyed, by Victorian grave digging.

Subscribe to our quarterly newsletter

Surprisingly, there is a gap of 15m between the curtain wall and the inner bailey ditch, part of which was exposed in a nearby trial trench excavation in 1991. This might imply that the structure was placed on a low earthen bank or ringwork with its sloping sides taking up the intervening space. This earthwork cannot have been a high motte because, if so, the foundations of interior features would not have been dug to below the original ground level.

Figure 3: interpretation of GPR results, both copyright MoLA

The foundations of a square gatehouse (structures B and B2), measuring 6m by 6m, were revealed across the line of the curtain wall and would have provided access from the outer bailey to the north. Inside the curtain wall, the foundations of a large rectangular building measuring 12m by 7m (structure D) may have been the great hall which the documentary sources indicate was rebuilt after a fire in 1409-1410. The narrowness of the foundations might imply that the hall was timber built. Other foundations within the curtain wall (structures C and C2) suggest the presence of other buildings that may have predated the fire. A further building (structure E) may also be part of the castle but other foundations (structures F to J) are more likely to belong to eighteenth and nineteenth century outbuildings of the Green Dragon Hotel.

Subscribe to our quarterly newsletter

While the construction date of the castle is uncertain, pottery excavated from the castle ditch in 1991 suggests a date after 1100. This evidence, albeit limited, suggests that the castle was not built by the elder William Peveril in the immediate wake of the Norman Conquest but either by his son, as a response to civil war during the reign of King Stephen (1135-1154), or else by the de Ferrers who held the manor from 1199 to 1266.

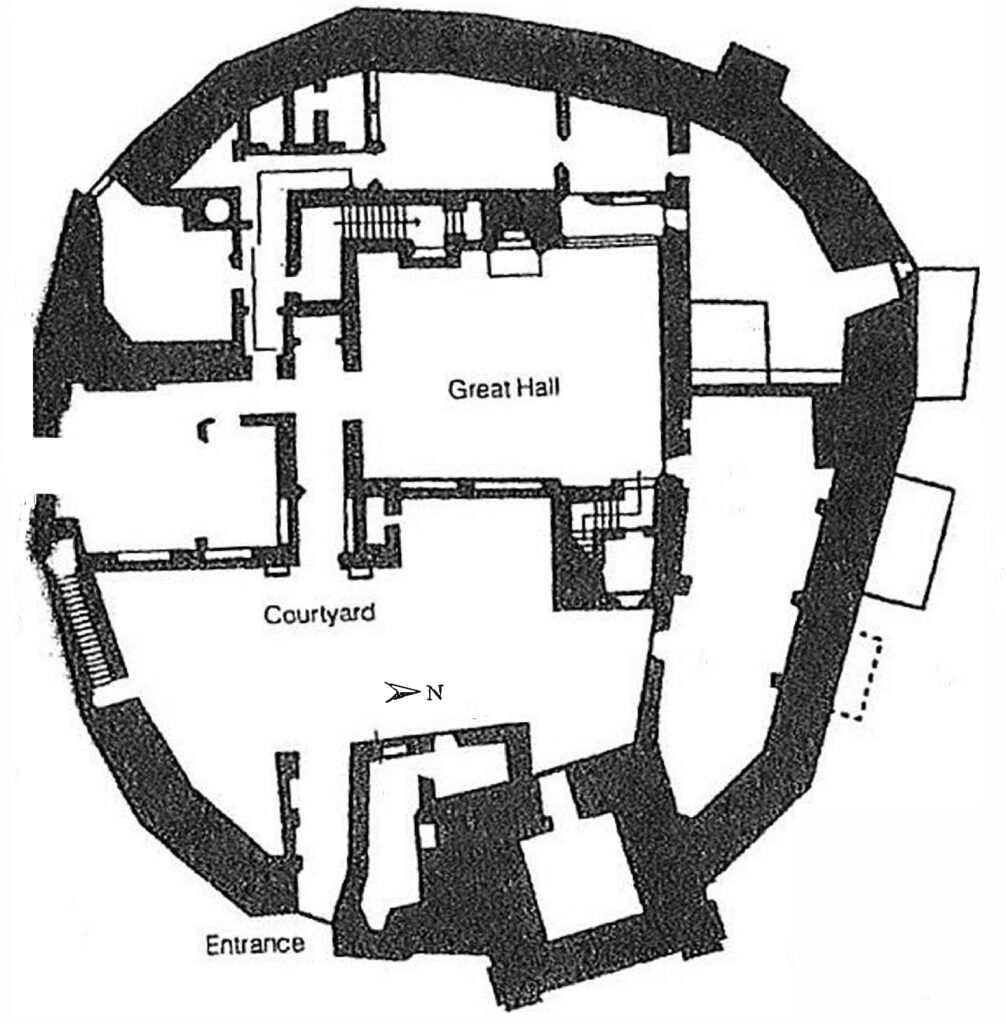

The results of this work, together with the limited trial trenching and documentary evidence, suggest that Higham Ferrers Castle may have looked similar to Tamworth Castle, Staffordshire, where the curtain wall is also an irregular polygon defining a slightly smaller area of 27.5m by 23m. Further similarities can be found in the central position of the fifteenth century great hall at Tamworth which was originally built of timber and has similar dimensions to the possible hall at Higham Ferrers, measuring at least 11m by 8m. To continue the analogy with Tamworth to its conclusion we should expect to see at Higham Ferrers a small courtyard between the gatehouse and hall, with the other castle main buildings including the King and Queen’s chambers, chapel and kitchen inside the line of the curtain wall (though as yet no structures have been identified at Higham Ferrers).

The purpose of the structures in the outer bailey and their date are uncertain, but they could represent service buildings including stables, barns, granaries or cowsheds.

The survey project also investigated an area further to the north which is known locally as Castle Field and is often considered to have been the site of the castle. However, no credible evidence of castle buildings was found in this area. Instead, the main finding was a large rectangular feature, believed to be the remains of a fishpond that appears on a map of Higham Ferrers produced in 1591.

Subscribe to our quarterly newsletter

You can read the full report here: Higham Ferrers, Northamptonshire | Castle Studies Trust