Lead Archaeologist on the Druminnor Castle excavation, Dr Colin Shepherd, looks at the results of the ground penetrating radar (GPR) survey of the castle in funded by the Castle Studies Trust in 2019 and what that means for future work at the site.

As a consequence of the GPR geophysics, that were generously funded by the Castle Studies Trust, we have a number of new and potentially interesting anomalies to be investigated. Furthermore, the GPR research has also been instrumental in clarifying other aspects of previously excavated evidence. This has been made possible as, contrary to most instances, the geophysics at Druminnor have been incorporated into the ongoing investigation rather than simply as a precursor to excavation.

Subscribe to our quarterly newsletter

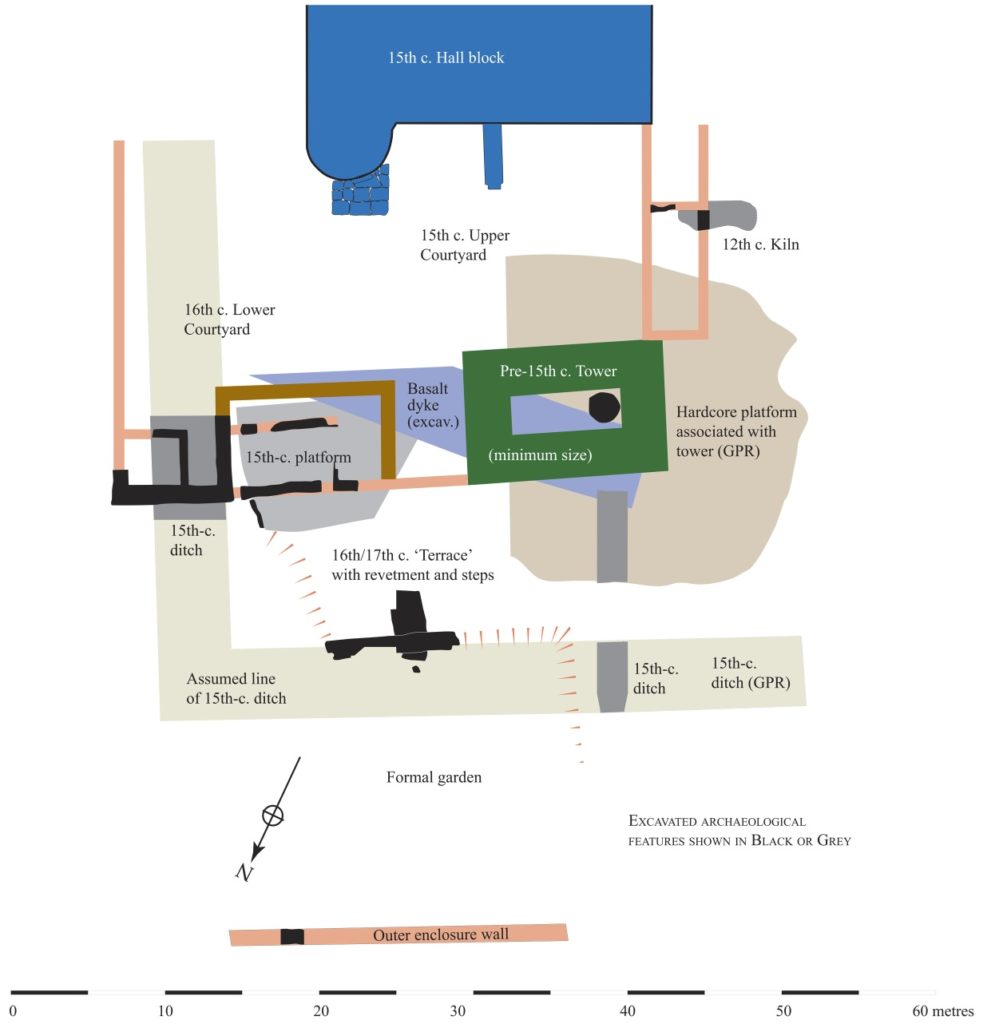

The GPR generated 286 ‘radargrams’ or sections across the site and much time and effort has gone into analyzing these. The radargrams were compared to actual excavated sections. This permitted the creation of a ‘key’ that has allowed us to extrapolate from the excavated sections to unexcavated parts of the site. As a result, we can, fairly comfortably, suggest a developmental plan of Druminnor spanning the 13th to 18th centuries (Figure 1).

The GPR has suggested the extent of a hardcore platform that appears to have supported the ‘Old Tower’. This was thought to have been the earliest part of the castle but without hard evidence. We hope to test the presumed limit of this platform as we extend our trench southwards from the well that sat within the tower. (As you will recall, the GPR alerted us to that remarkable feature that became a focus for our 2019 season.) The GPR suggests that there may be a revetment supporting the platform at that point. Also, any relationship between this platform and the mid 12th-century kiln will be important in attempting to date that platform and, by extension, the Old Tower itself.

The radargrams have also demonstrated the probable line of a terrace and sunken formal garden (red hachures on plan) and permits the excavated section of revetment and steps (shown in black) to be placed in its proper context. This garden probably dates to the 16th or 17th century, though exactly when is still debatable. The construction of the terrace removed all trace of the earlier (early to mid 15th century) ditch and so must post-date that. A late 17th-century Dutch pipe bowl found in the fill of a post hole associated with the steps suggests its removal at around that time or shortly thereafter. No trace of the terrace appears on the estate plans of c.1770.

The line of the defensive ditch has been shown by the radargrams to extend westwards from the excavated portion in Trench 11. This gives us an accurate alignment permitting its course to be drawn, even though the middle section was removed by the terrace. Where its return is at the western end of the site is still a mystery. The eastern arm was excavated in Trench 2 lying beneath the later (early 16th-century) lower courtyard. The 15th-century upper courtyard incorporated the tower with the surviving hall block (shown in blue). The courtyard’s west range can be estimated from remains found during the kiln excavation, but its eastern boundary was removed when the lower courtyard was added.

Finally, the GPR revealed the line of the outer enclosure wall as depicted on the estate plans. This was sampled in 2019 and the base of the wall found. The date of this feature is presently unknown and further work needs to be done to try to clarify that matter.

Sadly, work planned for 2020 included the extension of the ‘well trench’ in the car park to look for the possible revetment suggested by the GPR as well as opening a much bigger area across the outer enclosure wall, as located by GPR. This sits beneath a good metre and a half of later landscaping material (see picture, courtesy of Iain Ralston) and, for safety and archaeological reasons, demands a much larger trench. The keyhole sample trench indicates good survival and, it is hoped, evidence will be found to date the feature and to help explain when this became the northern boundary of the castle enclosure.

The excavated evidence together with the GPR results permit this developmental plan to be made and rough dates affixed. It is worth noting that, prior to our investigations, Druminnor was believed to have consisted solely of the surviving hall block with an attached tower at its western end. Everything not in blue on the plan, therefore, was formerly completely unknown.

Access in 2021 is still, sadly, in the laps of the Gods owing to Covid, but it is hoped that we will be able to get back on track later this year to look for more goodies!

![[10] Druminnor Castle - "Woops!"](https://farm6.staticflickr.com/5125/5340893447_176baa5abf_b.jpg)