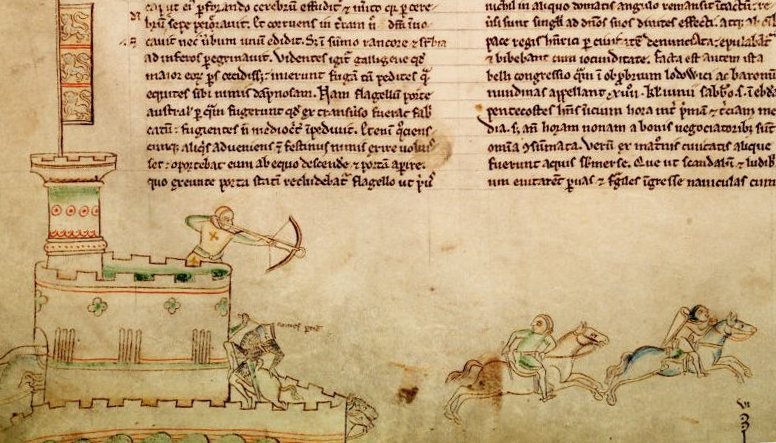

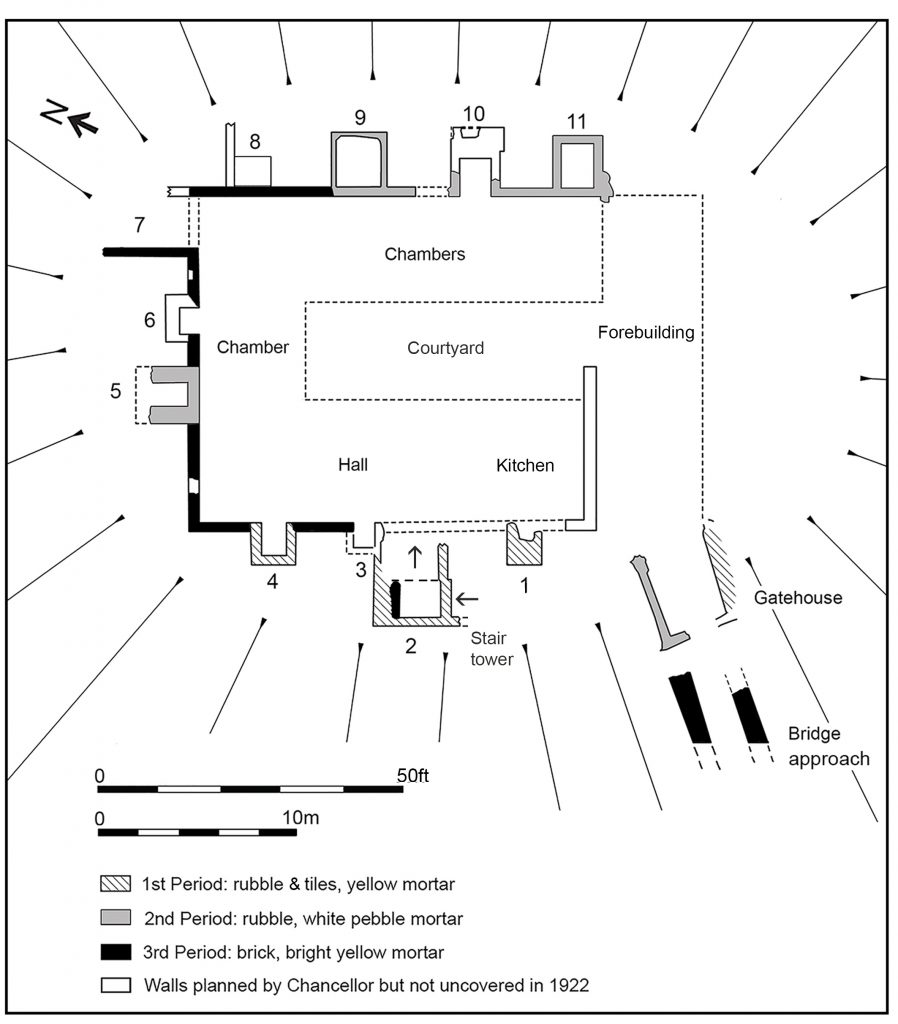

“King Henry II built the great tower at Dover Castle” is the kind of statement you will hear when visiting one of this country’s magnificent fortresses. But the King himself never lifted a single tool to get any castle built. While the hard manual work was done by labourers, and the finer details worked by master stone masons and carpenters hired because of their great skills, the general plan as well as the day to day running of the construction would have been overseen by an engineer-architect. Under Henry II, records survive telling us who they were (in this case, Maurice the engineer) but in most instances they are anonymous.

This anonymity is not a surprise: the writers of medieval chronicles were interested only in the great who ruled society – kings, bishops, great lords. It was this gap that persuaded me to write my book The Medieval military engineer. From the Roman Empire to the sixteenth century (Boydell Press 2018).

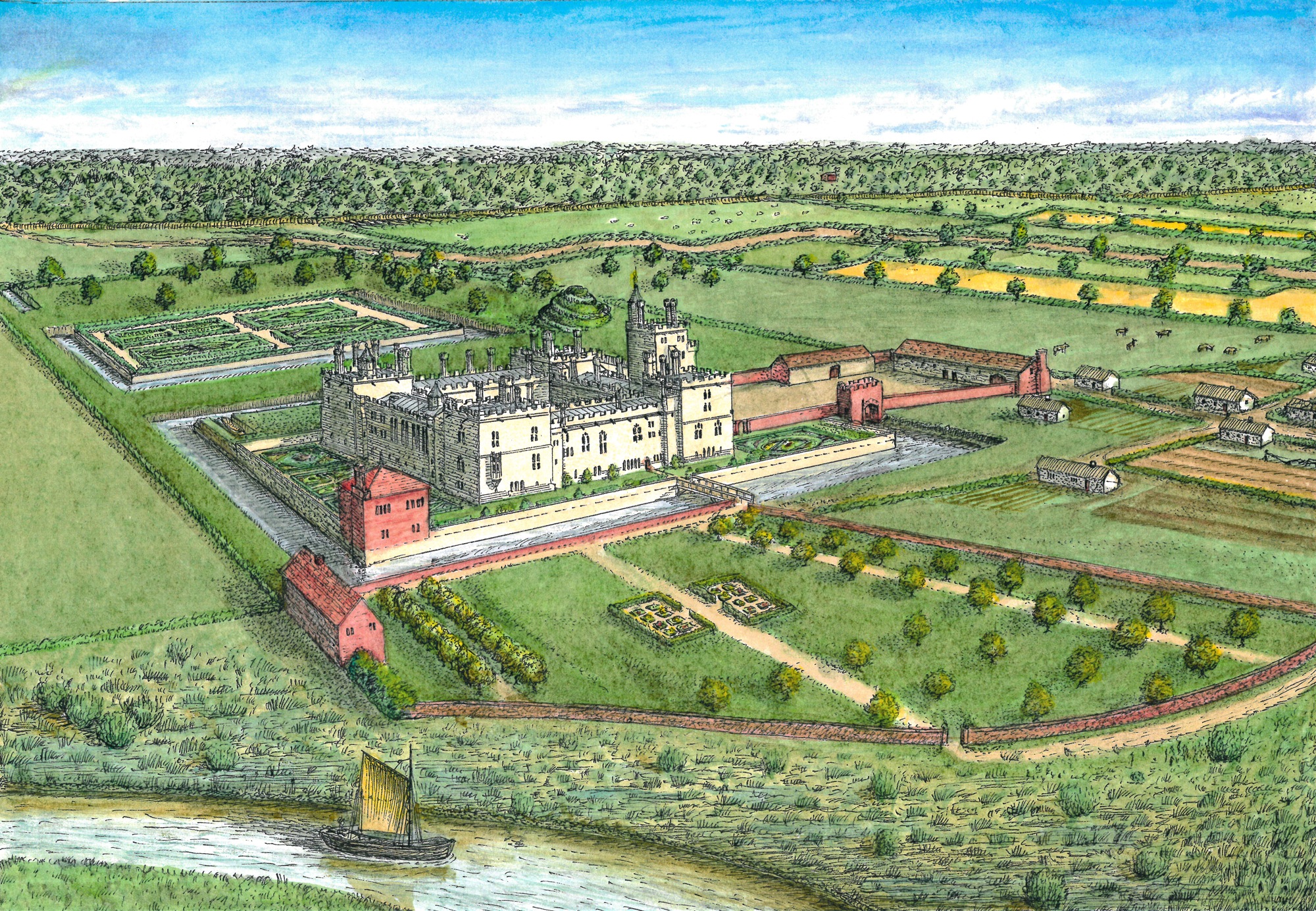

Today, sappers and engineers form a key part of every state’s army, and was also true of imperial Rome. But in medieval times craftsmen were hired to carry out engineering roles and quite often the same people would have many skills, so that alongside building castles they might also design bridges, churches and cathedrals, or oversee the creation of, and sometimes operate, siege weapons. Because they were commoners, and with only a handful of exceptions, their names were not recorded throughout early medieval times. Often we only know them when (like Maurice) records start surviving showing what they were paid for their work. The great lords who also had hands-on military engineering skills were named in history, but were a tiny handful.

Many interesting questions become easier to answer as more records survive, such as how much did these engineers actually know, how they learnt their skills, how knowledge was transmitted across generations, and what part did they play as technology became more sophisticated?

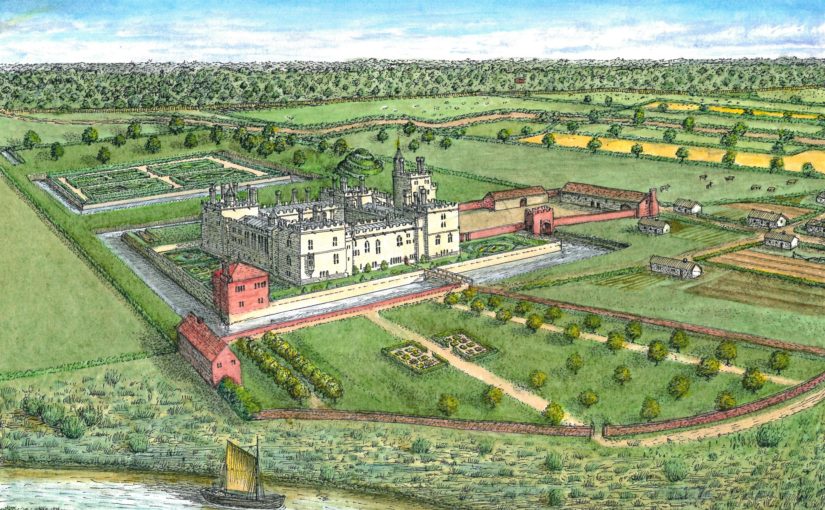

Historians no longer see the years between the end of the western Roman empire and the European renaissance of the fifteenth century as one long period of ignorance, and we are more aware that change and improvement were continuous, witnessed with the development of ever more spectacular cathedrals and castles, but also mundane but vital skills such as bridge and ship building, irrigation schemes, and military equipment such as siege artillery – the trebuchet, taken up across Europe and the Islamic lands during the thirteenth century, was a game-changer, before giving way to gunpowder artillery during the fourteenth.

Change happened because people questioned existing conventions and came up with new ideas, but also because they developed the skills to put them into practice. It is time to give them the credit they are entitled to. Next time you visit a large stone castle, ask not just which lord lived there and paid for it, but who actually designed it, and admire their skills; and if despite its strength it was captured in a siege, who built the wooden engines that do not survive, or who undermined it, which decided the outcome?

Peter Purton, DPhil (Oxon), FSA.