With our 10 year anniversary conference on Saturday 10 June at the University of Winchester fast approaching as a taster here for the conference here are the abstracts for Dr Karen Dempsey’s keynote and all 15 papers being given.

Keynote

Who cares? Thinking again about medieval castles – Dr Karen Dempsey

The foundation statement of the Castle Studies Group underlined the need to research castles not as an isolated phenomenon, but in a holistic manner that explored their wider inter-relationships with medieval economy, society, and environment. Over the past few decades, castles have received such attention with increasingly more scholarship considering gender and space including a particular focus on the garden. However, despite these excellent additions, castle studies has often appeared to somewhat lag behind theoretically in archaeology. In this paper, it is not my intention to critique this nor do I want give you an historiography of the discipline or even an account of current thinking. I want to root something different into our studies, to offer another way of thinking or engaging with the past. I want to consider care as a structing principle within society and offer medieval castle households as a case-study.

Session One

The Medieval towers of Central Greece – Dr Andrew Blackler

The great tower, as R Allen Brown once wrote, is the essence of the castle. The archaeological focus on Greece’s classical heritage has overshadowed the existence of hundreds of such medieval towers in Greece. This is a period during which western Crusaders, and Turkish and Arab forces vied with the Byzantine empire for control of the eastern Mediterranean. Whilst some research has been undertaken into major fortresses of the region little is known about the smaller castles, evidence of whose existence survives in these austere towers, often rising to a height of nearly twenty metres.

Most are undocumented, and neither their builders nor function in the landscape is known. The present literature with little hard evidence defines the towers as colonial structures built to control the local Greek population and display the power of western (Norman, Frankish, Italian, Catalan) feudal landlords over their estates. Research by the author over the last ten years challenges this view. This paper discusses how we need to comprehend their architecture, their immediate built environment, and function within the landscape in a much more nuanced way.

Laboratory analysis of wood and mortar samples (due in March 2023 – sponsored by the Castle Studies Trust) from seven towers on Euboea, an island off the eastern seabord of Central Greece, is expected to throw further light on their construction date and therefore the historical context within which they were built. The conclusions from this will also be presented.

The Lower Thames Fortifications from 1380 to 1872 – Paul Mersh

This paper traces the development of fortifications that were built to defend London from attack along the Thames and their impact on the local area. From the 14th century until the second world war London was defended by a line of ‘outer defenses’ in the lower Thames area. These defenses began with Cooling Castle which was built around 1380 to defend against French raids. This castle was one of the first to be built for cannons.

The defenses were substantially upgraded with block houses in the 16th century, a star shaped fort at Tilbury in the 17th century and gun emplacements in Gravesend in the 18th century. In 1860 the Royal Commission on the Defense of the United Kingdom recommended that the forts at Gravesend and Tilbury be substantially upgraded and three new forts be built in the Lower Thames area. Once again, these upgraded defenses were built to defend against the French. The building of these forts was supervised by Charles Gordon – Gordon of Khartoum.

What dictated the design of these fortifications? There were two factors, one was the

design of ships. The second was improved ships’ guns. It was like a five hundred year

arms race. The building of these later forts had a considerable impact on the local area.

Some £50,000 was allocated for the work on the Lower Thames Forts, this is the

equivalent of £15,000,000 in today’s money. This paper concludes by examining this

impact.

Castles and urban settlements under the rule of Matilda of Tuscany-Canossa in the late 11th and early 12th century Dr Rosa Smurra

The paper aims to explore the connections between Matilda of Tuscany-Canossa’s castles and the emergent communes in Italy.

Castles were of great importance in the establishment of the Canossa dynastic rule (10th-12th centuries) and the maintenance of their power for at least five generations. Castles were crucial particularly during the period of the emergence of the communes in Italy, which marked a fundamental change in the government and political regimes of all the major cities and towns in northern Italy, including, of course, those under Matilda’s rule, the Canossa last ruler. Matilda of Tuscany-Canossa (1046-1115) is among the most significant female rulers of the European Middle Ages. She was countess and duchess of a vast domain, stretching from Lombardy to Latium, which she ruled in her own right. Although a vassal of the German emperors and bound to them by blood ties, she assisted seven popes, thus determining the fate of the so-called Investiture Controversy and eventually of the whole of Christendom.

What was the role played by the Matilda castles in these circumstances and especially for the nascent communes? How did Matilda’s castles condition these institutional changes?

What was their impact on the establishment and evolution of the network of urban settlements that still characterises the landscape of the Po valley today?

Analysis of a quite rich documentary record produced before and during the Matilda rule and integrated into the GIS platform of a digital atlas exploring both the environment and communication network attempt to answer these questions.

To come along to the conference sign up here: Castle Studies Present and Future: Castle Studies Trust conference Tickets, Sat 10 Jun 2023 at 10:00 | Eventbrite

Session Two

Childbirth in the castle: Alice Thornton’s trip to Middleham, 1644 – Dr Jo Edge

Alice Thornton (1626-1707), writing one of her four autobiographies in the late 17th century, described an incident which took place decades earlier. While travelling on horseback to Middleham Castle in August 1644, she nearly drowned crossing the river. 18-year-old Alice made this trip because her older sister, Katherine Danby, was in labour for the 15th time:

At that time Sir Thomas Danby was forced with my sister and children to be in safety, from the Parliament forces, he being for King Charles the first, to Middleham Castle, a garrison under my Lord Loftus. There she was delivered of her first son Francis Danby. My sister got my Lord Loftus and myself with Co. Branlen for witness.

Summer 1644 was a dangerous time to be in North Yorkshire, especially as a young, royalist woman. Just the month before, Parliamentarian soldiers been victorious at the battle of Marston Moor, and soldiers were garrisoned everywhere. Danby was fugitive, and he and his wife and children had sought refuge at Middleham, owned by family friends and fellow royalists Edward and Jane Loftus.

We know about royal children born in castles – and indeed, Edward, son of Richard III – had been born at Middleham some 160 years earlier. But this wasn’t a birth of a royal, nor one that happened in normal circumstances. This paper will examine and imagine the feminine space of the birthing chamber within a garrisoned castle, using the work of Roberta Gilchrist, Karen Dempsey and Rachel Delman as starting points.

Holding Court at Windsor: the Royal Household under George III – Amanda Westcott

The prevalence of his “Farmer George” persona often obscures the nature of courtly lifestyles that George III facilitated outside of London among his closest aristocratic courtiers and throughout the wider royal household. The study of alternative courtly venues is a helpful approach to the circles of sociability that, from the late eighteenth century, were more frequently gathered in settings beyond St. James’s Palace. Beginning in the early 1780s, when the king and his queen consort, Charlotte, assembled their large family and circle of attendants at Windsor Castle, they likewise convened a community with distinctive spatial features and social structures. Time spent living in the countryside established an integrated network of courtiers supported by shared interests in the period’s rural and leisured pursuits especially accommodated at Windsor, including hunting, architecture and landscape design, music, country house tourism, and the enlightened study of subjects like botany, agriculture, and astronomy. In particular, the gendered elements at court and the organization of Queen Charlotte’s own household provide a unique lens to the castle’s importance as a courtly venue. Themes concerning the royal household’s spatial accommodation at Windsor, as well as the social hierarchies instilled in royal routine there, further aid discussions of the variety of social identities cultivated at this court in addition to the nature of late-Hanoverian kingship at its helm.

Domesticity, militarisation, and lordly power during the British Civil Wars – Tristan Griffith

This paper will explore the continuing importance of the castle as a lordly seat during the British Civil Wars of the mid-seventeenth century: this builds on the work of scholars such as Coulson, who long ago demonstrated the inadequacy of a binary fortified/domestic dichotomy in the study of structures such as castles and other fortified dwellings. As its principle case studies it will take Skipton Castle in Yorkshire and Lathom House, formerly in Lancashire, both large fortified dwellings which were renovated extensively in the decades before the Civil Wars, and which were turned into fortress garrisons by the Royalists—supporters of Charles I.

At Skipton, the renovations included the reconstruction of the castle gatehouse with a new dining room and neoplatonic grotto, but also additional gunloops; this demonstrated that the castle’s owners, the Clifford Earls of Cumberland, continued to prize both military preparedness and conspicuous luxury to assert their supremacy over the local gentry. During the Civil Wars the Cliffords’ network of gentry supporters formed the basis for the Royalist garrison—most of whose officers were local gentlemen. At Lathom, the seat of the Stanley family, the Countess of Derby levered both her home’s impressive defences and its position at the centre of the Stanley powerbase in Lancashire to hold it against a lengthy and destructive Parliamentarian siege; Lathom’s antebellum magnificence had a definite military result during the conflict—Lady Derby’s supporters held the castle until relieved by Prince Rupert.

To come along to the conference sign up here: Castle Studies Present and Future: Castle Studies Trust conference Tickets, Sat 10 Jun 2023 at 10:00 | Eventbrite

Session 3

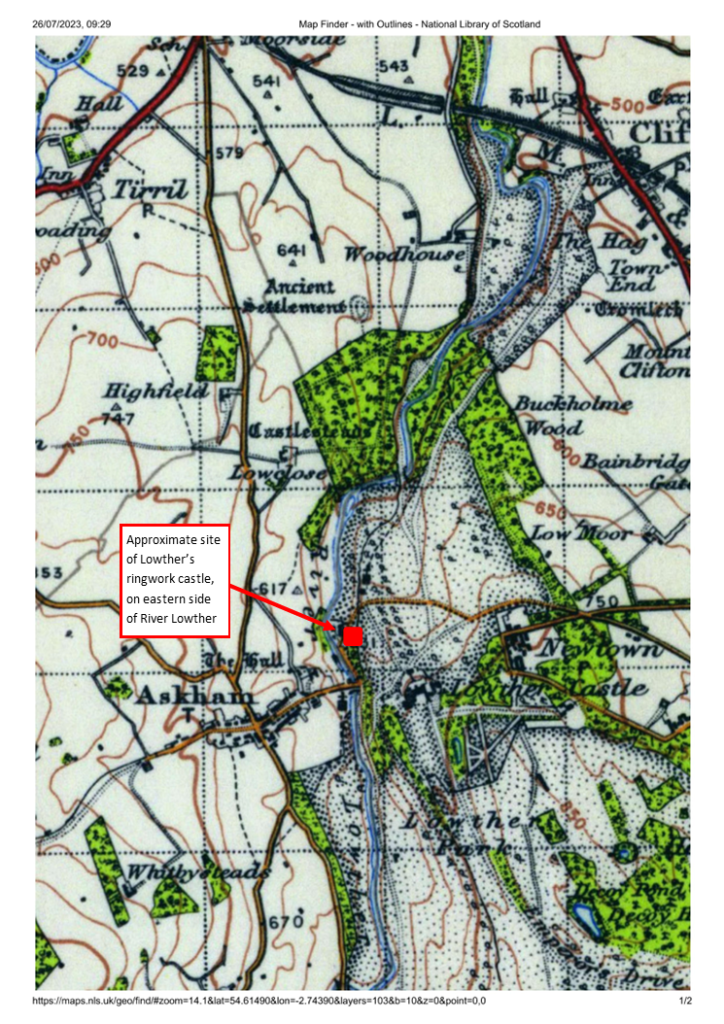

Connecting medieval castles and the Legacies of Slavery: evidence and significance from two English case studies Dr Will Wyeth

This paper presents findings from investigations into the legacies of Slavery at two ruined medieval castles in the care of English Heritage: Beeston Castle (Cheshire) and Brougham Castle (Cumbria). In the context of ongoing public discourse in the United Kingdom around the ways in which the country’s colonial and imperial past is discussed, as well as an established body of research exploring the connections between the slave trade and country houses, it is timely to consider the extent to which monuments from the medieval past are entwined with the profits from Slavery. A recent revision of the guidebooks for both properties has occasioned a closer examination of the lives and legacies of individuals connected to the ownership and restoration these sites in the middle of the 19th century. By constructing a picture of wealth, privilege and society in which these individuals lived over several decades of this period, it is possible to establish with greater confidence the extent to which the legacies of the Slavery form part of the construction these castles’ medieval past in the post-medieval era. The significance of these connections is discussed.

Foundation Myth and ‘Medieval’ Identity: The case of Bungay Castle – Dr Laura-Jane Richardson

Bungay Castle was founded sometime in the 12th century, and overlooks the Waveney Valley, the geographical divide between Norfolk and Suffolk. The Castle was part-excavated by an amateur team in 1935-36, and very little archaeological work has taken place on the site since. In the aftermath of the First World War, Bungay Castle played an important local role reflecting Englishness and heritage identity. In the light of these excavations and a growing awareness of the benefits of heritage tourism at the time, the Castle was used in the development of local mythology and historic misinterpretation during the 1930s and 1940s. This paper will examine the development of these mythologies alongside the campaign to adopt the Castle by the townsfolk, and reflect on the modern relationship between imagined castle life, medieval pasts and heritage identity in this small market town.

Jews’ Towers in England Castles: The Cases of Lincoln, London and Winchester – Dean Irwin

In his 1982 article, ‘Jews and castles in medieval England’, Vivian D. Lipman considered the relationship of between Jews and castles. Although some of his conclusions have been challenged by Robert C. Stacey and myself, it is clear that castles were an important part of Anglo-Jewish life between 1066 and 1290. Increasingly, Jews are being included in the presentation of sites to the general public, although this typically follows the ‘Dark Tourism’ route. Heavy emphasis was given to the role of a castle as a prison and site of execution in the recent rebranding of the Tower of London. Equally, Clifford’s Tower (York) understandably focuses on the massacre of 16-17 March 1190. This paper, in contrast, focuses on the towers which were associated with the Jews at the castles of Lincoln (Aaron’s Tower), London (Hagin’s Tower), and Winchester (Jews’ Tower). In so doing, it argues that the Jews occupied a legitimate space within English castles as part of the royal administration of the community. Far from being sites purely of victimhood, castles were generally sites where leading Jew worked with royal officials (often the sheriff) on communal administration. This is an underexplored element of both Castle Studies and Anglo-Jewish history, but emphasises that we should not simply view the relationship between castles and Jews as one of oppression, imprisonment, and violence. Rather, it argues for the inclusion of minority groups within narratives of castles in a collaborative sense.

To come along to the conference sign up here: Castle Studies Present and Future: Castle Studies Trust conference Tickets, Sat 10 Jun 2023 at 10:00 | Eventbrite

Session 4

New theories, old practices? Examining visitors’ perceptions of castles – Lynsey McLaughlin

‘Ask anyone to visualise the Middle Ages and they will, almost invariably, conjure up the image of the castle’ (Liddiard, 2005, xi).

There has been a transition in the understanding of castles in the later part of the 20th century in castle studies. The focus has shifted from one heavily centred around a military interpretation, to placing them in a wider context, particularly considering their role as symbols of status. Whilst this new approach has been largely unchallenged within academia, organisations that open castles to the public have been accused of retaining the overtly military interpretation to lure visitors through the door. My PhD asks whether castle sites really do capitalise on medievalist tropes, and what effect this has on the people that visit. This presentation reviews the results from four castles: Richmond, Corfe, Bodiam and Orford. It considers visitor data, interviews with staff and presentation methods used by castles. The results demonstrate that, whilst the castle and the people who manage it do utilise medievalist tropes, visitors’ perceptions and understanding of the castle are not affected. In addition, tensions appeared between different staff groups over what they perceived visitors wanted.

The Medieval Castle through a Post-Medieval Lens – Ann Walton

Long relegated to the category of military history, English castles have enjoyed a recent growth in scholarly interest. A survey of recent publications shows that most focus on the medieval history of the buildings, however, as the urban castles of the Conquest approach the end of their first millennium, it is important to acknowledge that they did not wait patiently to become tourist sites but continued to develop over time in both function and appearance.

My paper focuses on the post-medieval life of English urban castles through the case

study of Lincoln Castle, and seeks to answer the following question: In what ways is the survival of urban castles predicated on their ability to adapt to evolving needs and functions, and how did popular and scholarly attitudes towards castles affect their continued use and preservation? In addition to functional and physical alterations made to castles during their post-medieval history, I will explore the role played by developments such as Antiquarianism and Romanticism in the

preservation of these structures, and more importantly, in the shaping of modern perceptions of the medieval castle.

Through this paper I contextualize the post-medieval life of Lincoln Castle within

contemporary social, scholarly and architectural trends. By giving the past five hundred years of the castle’s history the attention usually reserved for the earliest period of its development I will analyze the context of these later stages highlighting the impact of post-medieval castle development on our understanding of the castle as a whole.

1283 in 1983: Castles, Commoditization and the Commemoration of the Medieval Welsh Past – Dr Euryn Rhys Roberts,

Do come to the Wales Festival of Castles. We’ve been preparing it for 700 years” was the cheerful invitation emblazoned on the pages of the Chicago Tribune on 10 April 1983. The Wales Festival of Castles, or Cestyll ’83 (Castles ’83) as it was branded, was a Wales Tourist Board and British Tourist Authority marketing promotion to boost the international profile of Wales as a holiday destination. Yet, what was intended as an uncontentious tourist promotion became a matter of some controversy, with some seeing the Festival as a celebration of the 1282-3 conquest of Wales writ large and the castles of Edward I. Drawing on archival material from local and national archives, this paper sets out to trace the history of the Festival and to provide a commentary on how the medieval Welsh past was used and abused in the early 1980s. On the one hand, it is a story of how competing voices struggled over the image of the castle in Wales, and on the other of how the past came to colour the discourses and practices of those who sought to promote Wales as a holiday destination and of those who felt compelled to protest against the Festival.

To come along to the conference sign up here: Castle Studies Present and Future: Castle Studies Trust conference Tickets, Sat 10 Jun 2023 at 10:00 | Eventbrite

Session Five

Hornby Castle Wensleydale North Yorkshire:- “An Elite Holiday Home of the Later Middle Ages” Dr Erik Matthews

Fieldwork at Hornby Castle Wensleydale North Yorkshire undertaken since 2010 has thrown significant light on a moated hunting lodge complex developed first by the Dukes of Brittany in the early 12th Century and then “modernised” by the Nevilles of Redbourne in Lincolnshire in the 14th Century. I shall discuss the important role played by the development of castle sites as places of elite bonding and recreation through hunting and other pursuits in demonstrating the status of the owner and developing the essential links with others of the same class as part of a common European wide culture. I will focus in on the information gleaned from Hornby in terms of the Park and its layout, the hunting lodge and its surroundings notably the development of a surrounding “watery landscape” and I shall also reference the evidence of an elite “material culture of taste” which has come to light. I shall draw parallels with the Country House of the Late 17th/18th Century and look for conclusions in terms of better understanding the interaction of the Castle with its surrounding landscape and its purpose.

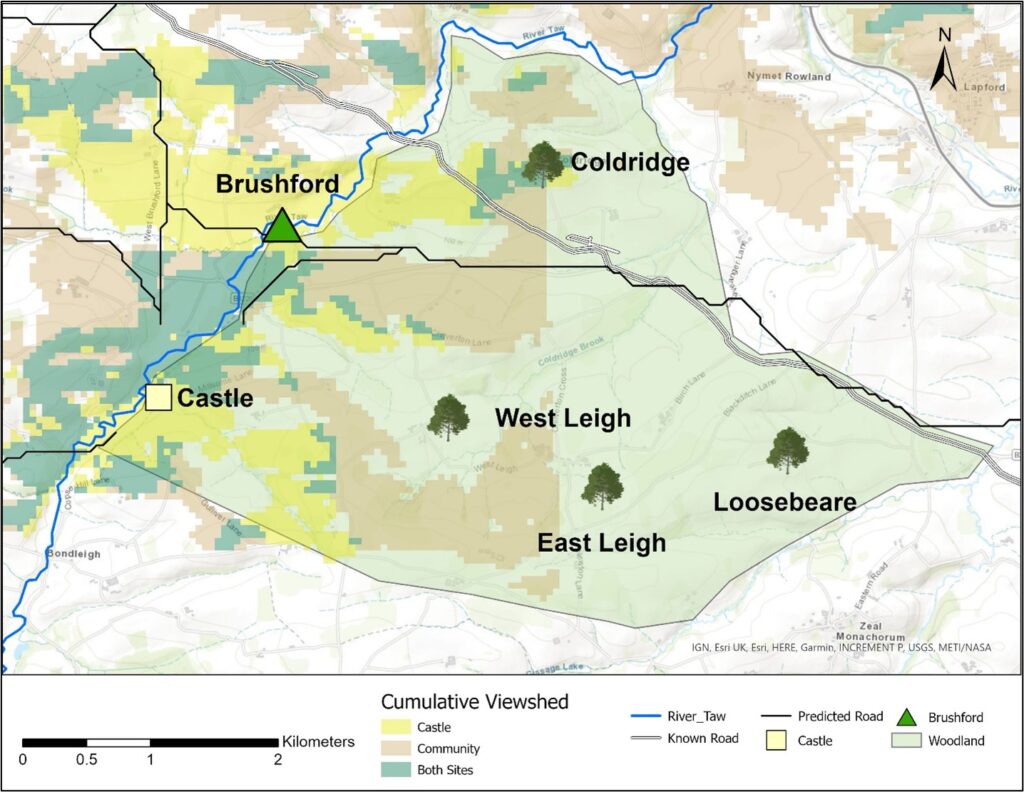

The Clockwork Castle: Interactions between the castle and the temporalities of the landscape, and their implications for surrounding medieval communities – Arthur Redmonds

The underutilisation of theoretical approaches within Later Medieval archaeology and castle studies has been highlighted by numerous scholars, yet recent studies and this symposium seek to demonstrate new complementary approaches. This paper aims to contribute to this reimagining, utilising a theoretical framework based around Tim Ingold’s concepts of the dwelling perspective and the taskscape to demonstrate the temporal influence of the castle.

These concepts will allow this paper to demonstrate the considerable impacts the presence of a castle might have had on multiple forms of temporality within the landscape. Taskscape as a concept is inherently focused on viewing place and interactions as temporality materialised, and it can be shown that castle builders and occupants were more than aware of the implications of dominion over time. Through centring itself in everyday, seasonal, and more long-term environmental cycles, the castle drastically impacted local social memory, lived experiences, and notions of social order. All became warped according to the social ambition of castle builders, and their place in time.

This holistic scope also allows for underutilised methodological avenues to be explored within castle studies, namely the landscape materiality of the everyday communities surrounding the castle. ‘Big data’ approaches to archaeology continue to allow new avenues of exploration, and spatially located Portable Antiquity Scheme data will be integrated into the conclusions of this paper alongside more orthodox approaches to castle studies.

Overall, this paper will explore a new vision of the castle as a part of the interwoven temporalities of the medieval taskscape.

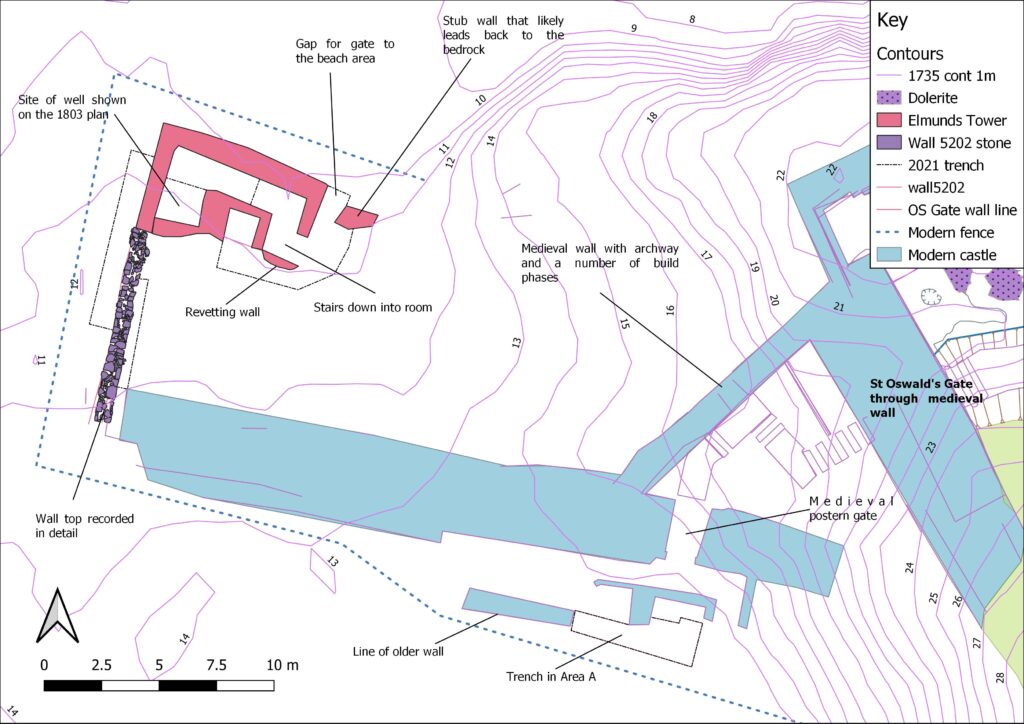

Countess Isabella de Fortibus and her building works at Carisbrooke Castle – Dr Therron Welsted

Isabella de Fortibus , or Forz, (c.1237-1293), after the deaths of her husband, William de Forz, count of Aumale in 1260 and her brother, Baldwin de Redvers earl of Devon, two year later, became an extremely rich landholder. She is best known for her apparent love of litigation, with many court cases being held in her name, often concurrently.

This paper looks at a different side to her life, her as the builder of Carisbrooke Castle (Isle of Wight), which became her primary residence after inheriting it from her brother. Through looking at the surviving building accounts, it is clear there was essentially a total reorganisation of the castle with many new constructions, in this period.

There has been little critical analysis of the building works undertaken for Isabella since the 1890s when Percy Stone, an architect and archaeologist, undertook a detailed study of Carisbrooke Castle. This paper presents the ongoing research about the castle in the thirteenth century, as part of a current project reassessing Isabella’s life.

The interdisciplinary research behind the paper draws from a wide variety evidence, including the upstanding remains of the castle, both upstanding and archived; archaeological reports; and manuscript material, such as court records, accounts and a survey of the castle undertaken shortly after her death.

To come along to the conference sign up here: Castle Studies Present and Future: Castle Studies Trust conference Tickets, Sat 10 Jun 2023 at 10:00 | Eventbrite