On Monday 26 June the excavation and geophysical survey of Lowther’s medieval castle and Village gets underway, finishing on Friday 21 July. Here, project lead Sophie Therese Ambler from the University of Lancaster explains what she hopes the team of students and academics from the university and University of Central Lancaster with the support of Allen Archaeology hope to find over the next three weeks.

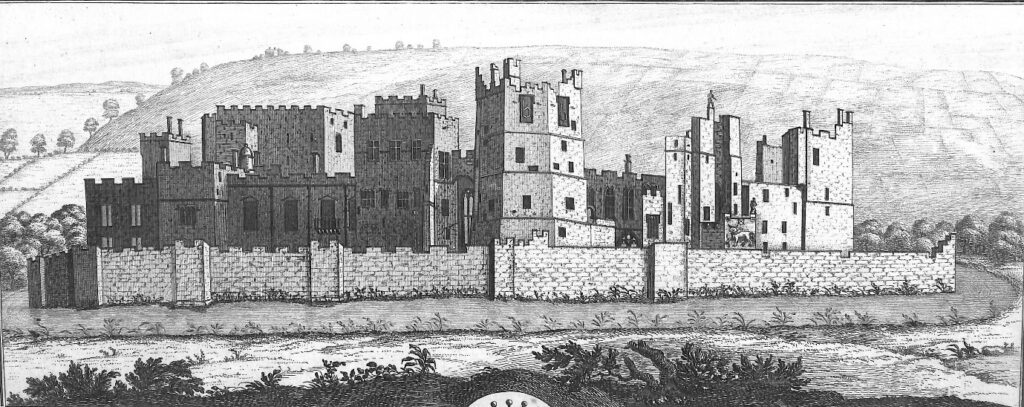

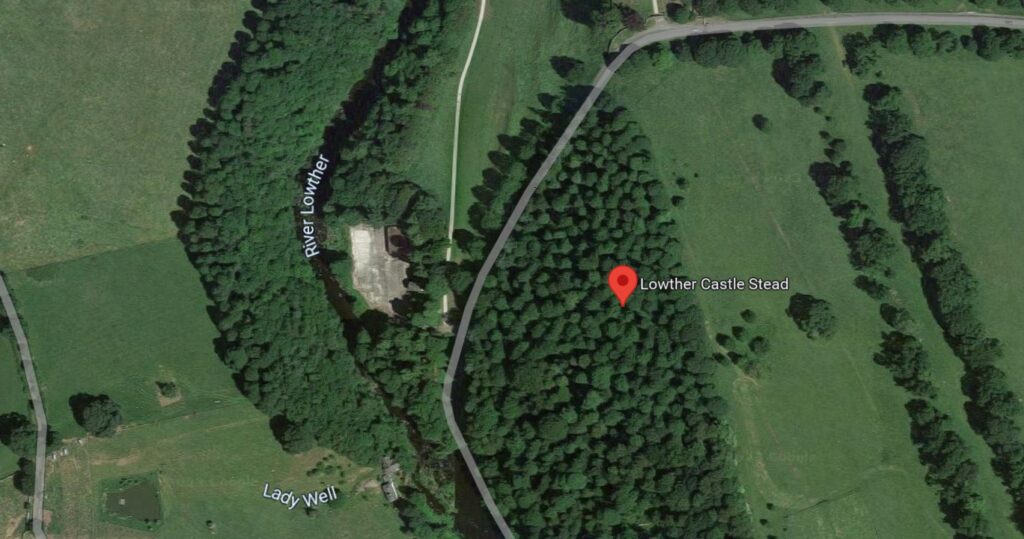

Overlooking the Bampton Valley on the edge of the Lake District, the picturesque ruins of Lowther’s nineteenth-century castle are one of the region’s most popular attractions. Less well known are the earthworks immediately to the north, the remains of a medieval castle and village. Preliminary work suggests the site may date to the late eleventh or early twelfth century. If so, it could provide rare evidence of the conquest of Cumbria by King William Rufus and his brother, King Henry I – a generation after the Normans seized control of the rest of England. The site is potentially of national significance but has never been fully investigated.

Subscribe to our quarterly newsletter

Who built the castle and its settlement, when and why? The Lowther Medieval Castle and Village project brings together historians and archaeologists from the North West to uncover the site’s biography.

The Castle Studies Trust has generously funded a survey and excavation, which will take place from 26 June to 21 July 2023. The project team brings together History at Lancaster University, Allen Archaeology, the University of Central Lancaster (UCLan) and Lowther Castle and Gardens Trust.

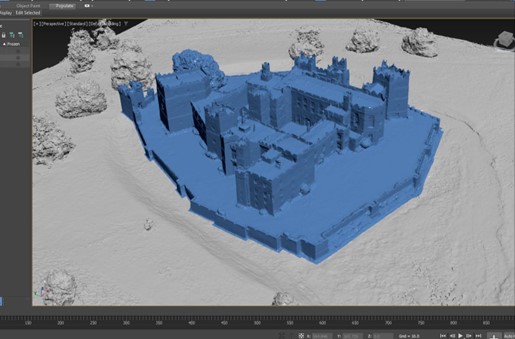

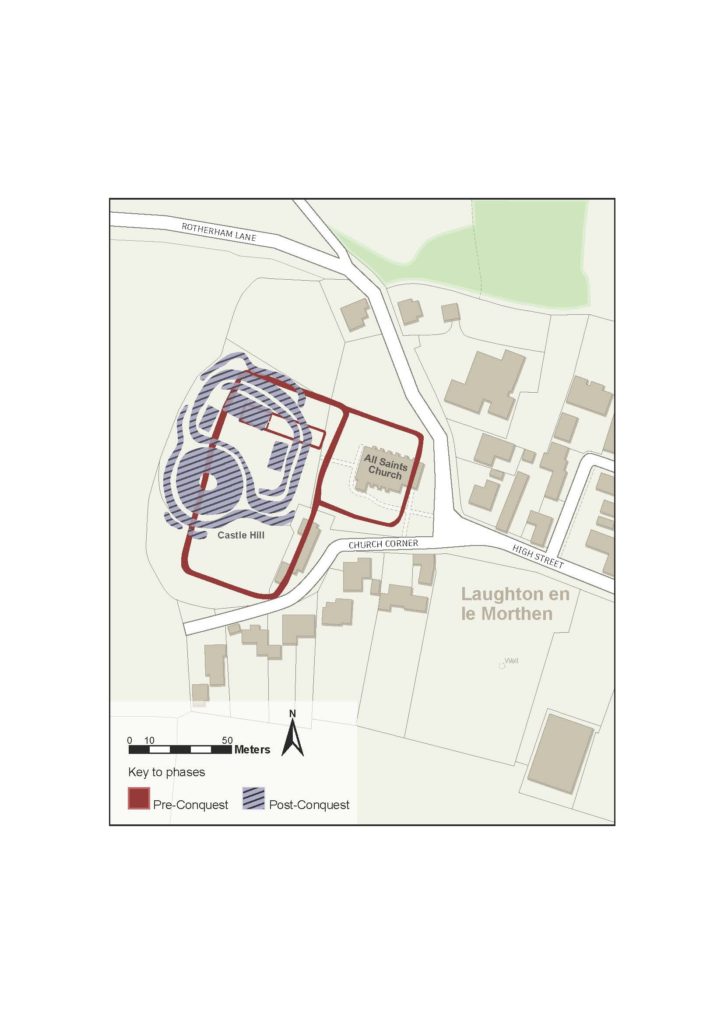

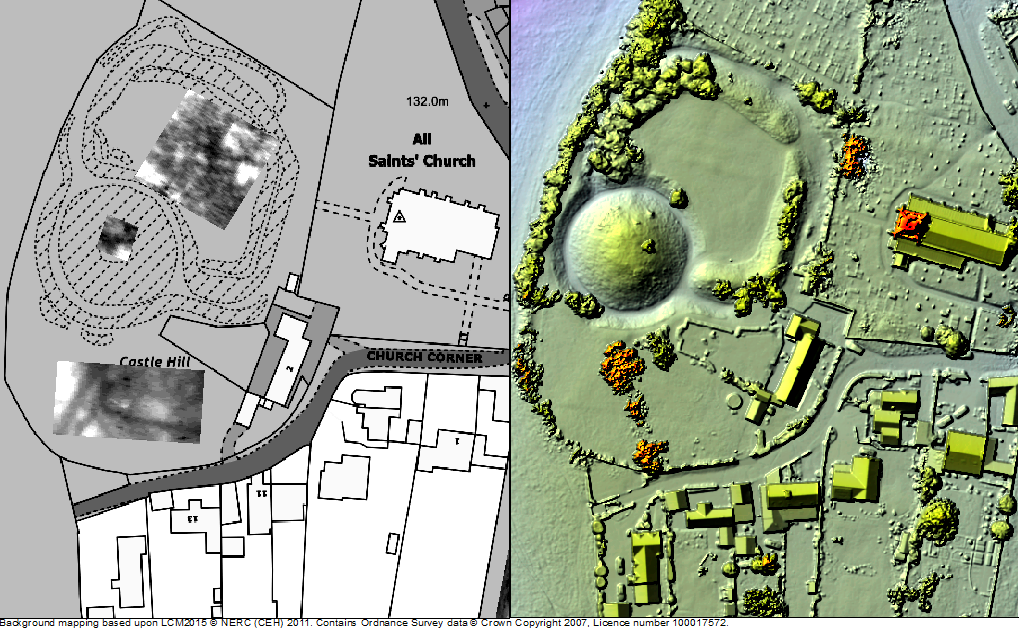

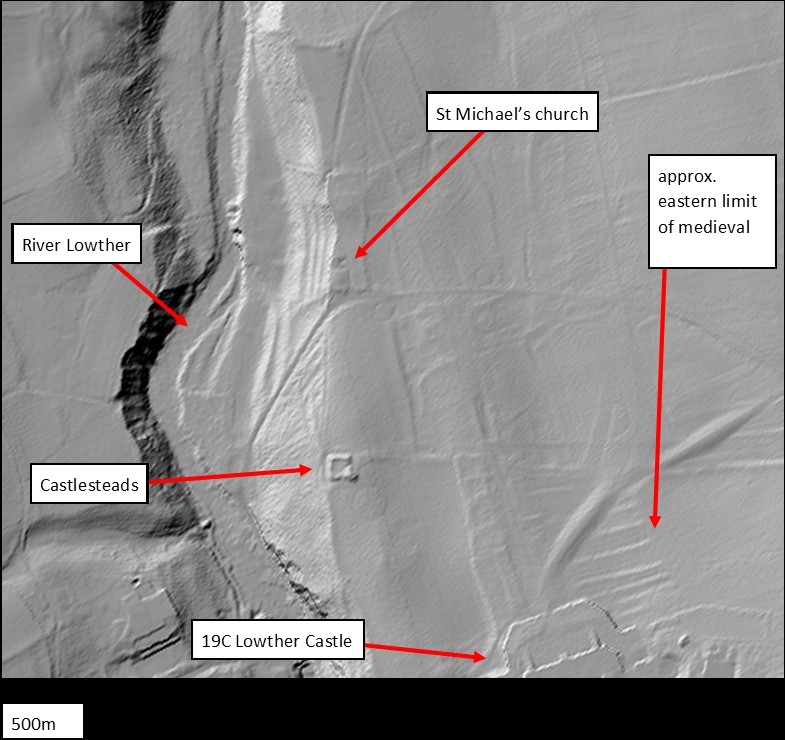

In the 1990s, the Lowther Estate commissioned a landscape report and earthwork survey. The report suggested that the Castlesteads earthwork dates to the early Norman era (late eleventh or early twelfth century), and categorised it as a ringwork, a characteristic rural castle form of the early post-Conquest period. It noted that the castle is ‘of considerable archaeological importance, particularly as it was potentially the original fortified site at Lowther’.

The report also suggested the village was integrally linked to the ringwork and ‘likely to have been a planned settlement, established under close manorial control’. The settlement, the report noted, ‘is of considerable importance being a fossilised medieval settlement and it has the potential to significantly inform our understanding of medieval nucleated settlement in Cumbria.’ At the north of the site stands St Michael’s church, which is medieval in origin and potentially related to the castle and settlement.

The extent and form of the site as a whole can now also be seen in LiDAR imaging (see image above), noting that the circular features are intrusions brought by landscaping after the demolition of the settlement in the seventeenth century.

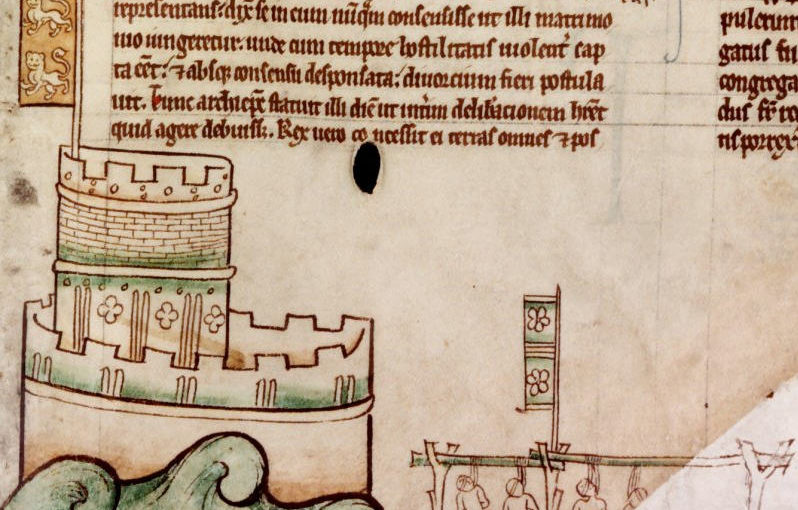

The working hypothesis is that the site dates to the Norman conquest of Cumbria. Unlike the rest of England, Co. Cumbria was not conquered by the Normans in 1066. The region was historically part of the Kingdom of Cumbria, which stretched from Strathclyde across the Solway. Then, while the Normans were conquering lowland England, the area from Lowther northwards was conquered by the Scottish king Máel Coluim III. Cumbria was only annexed by the Normans in 1092, when William the Conqueror’s son, William Rufus, led an expedition to the area. According to the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, the king then ‘sent many peasant people with their wives and cattle to live there and cultivate the land’.

Subscribe to our quarterly newsletter

Could Lowther’s medieval castle and village date from this era? Beyond the estimations provided by the earthwork survey, it has been suggested from place name and field pattern evidence that many medieval villages in this area of Cumbria were planned or remodelled settlements established following the 1092 annexation of Cumbria and peopled largely by colonists. But written evidence for Cumbria in this era is extremely sparse, so it is up to archaeology to test this theory. Whatever the investigation finds, the archaeology at Lowther offers a fantastic opportunity to understand rural castle building and life in medieval Cumbria.

In the first few days of the project, the team will conduct a geophysical survey, before opening trenches across the Castlesteads and settlement earthworks. Visitors to Lowther Castle will be able to visit the dig site – if you are in the area, please do come and say hello.

The team will be posting regular updates on the project in a Dig Diary here on the Castle Studies Trust website. You can also follow the project on Twitter, via the hastag #LowtherMedievalCastle

Meanwhile, further information is available on the project website:

https://www.lancaster.ac.uk/centre-for-war-and-diplomacy/lowther-medieval-castle/