Starting on September 11 2023, Dyfed Archaeological Trust, with Neil Ludlow, will undertake survey and recording at Picton Castle, near Haverfordwest in Pembrokeshire. This work, wholly funded by the Castle Studies Trust, will be fully analytical: it will provide a comprehensive record, underpinned by new research, in an attempt to unravel some of the mysteries of one of Wales’s – and indeed Britain’s – most enigmatic castles. Here Neil Ludlow and Phil Poucher from DAT explain more about the project.

Subscribe to our quarterly newsletter

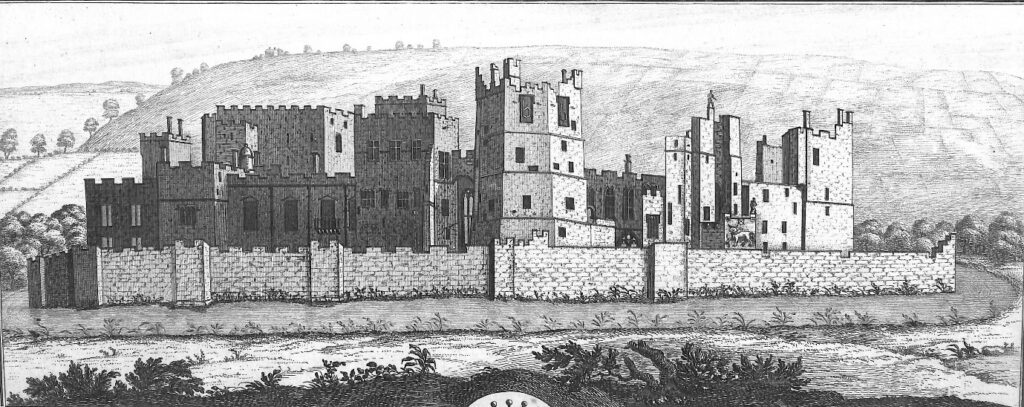

Picton Castle has been continuously occupied since it was built, and was substantially modified over the centuries, now wearing the veneer of an eighteenth-/nineteenth-century country house. Underneath, however, is a baronial castle from around 1300-20, of a highly unusual plan without close parallels in Britain and Ireland. A small, compact building, it comprised a hall-and-chamber block flanked for D-shaped towers, one near each corner, with a twin-towered gatehouse at one end – possibly unique – and a D-shaped tower, now lost, at the other. Variations on this basic ‘towered hall-block’ layout are seen in castles of similar date – and somewhat earlier – in the West Midlands, Scotland and the border, Ireland and even southwest France. But none fully mirror Picton’s plan-form – which might conceivably have been at least partly modelled on the large ‘keep-gatehouses’ of the late thirteenth century.

In addition, Picton shows strongly regional attributes including a first-floor hall, corbelled parapets and an abundance of squinched features in the external angles. The towers rise from pyramidal spur-buttresses with an unusual octagonal footprint, otherwise seen only in the gatehouses at St Briavels Castle (Gloucs.) and Tonbridge Castle (Kent). So a variety of influences – regional, national, international and purely personal – may lie behind design at Picton.

No structured survey and analysis of the castle has yet been undertaken, and it is fundamental questions like this that the present study will address. In addition, little is known of how the castle actually functioned. The service end of the hall is currently assumed to have lain towards the gatehouse, where blocked doorways possibly led to a buttery and pantry; at the opposite end, it’s possible that the two western towers were united to form a storeyed chamber-block, to which the lost D-shaped tower was a bedchamber. But medieval access arrangements are still a mystery, as are the use and relative status of many internal spaces. For instance, it’s speculated that a broad flight of steps might have led from the gatehouse, through a ‘processional’ archway, to the hall. But the ground floor is, unusually for the region, rib-vaulted throughout – can it really have been ‘cellarage’, or did it provide access (and an anteroom) to the hall and chamber? Two spiral stairs connect ground- and first-floor level, one of them with very broad treads – were the distinguished by the status of their users? Or did the vaulted ground-floor corridor lead to a stair accessing the high end of the hall?

Not all internal walls have been dated – some, at least, may be post-medieval. Similarly, it is clear that not all medieval features such as openings, entries, stairs, latrines, fireplaces, ovens and hearths have yet been identified. Their correct identification and dating will tell us a lot more about status and usage of interior spaces, and about circulation between them. The location of the kitchen and bakehouse – and method of water-supply – are also still unknown: were they separate from the main building? A chapel was in existence by the seventeenth century, and is assumed to have a medieval predecessor, but it is yet to be shown whether it lay over the gate-passage like its successor.

The 2023 work aims to resolve such questions, and to achieve a full understanding of the form, functions and affinities of the medieval building. A combination of total-station theodolite survey, drone photography, drawn elevations, a high-resolution photographic record and, where possible, 3D modelling will be used to obtain a comprehensive record, supported by new research. All evidence for medieval features, openings and architectural detail will be recorded, along with former levels and access between them, and any indication of different building campaigns. The report, with all survey drawings and photos, will be posted on the Castle Studies Trust website. 3D models will be accessible via Sketchfab.