Following the publication of the results of our Warkworth geophys survey, here is the second of the Trusts 2021 grant awards publishing their results on the building survey of Greasley Castle, Nottinghamshire . Here James Wright explains what he found during his survey.

When studying castles, it is important to try and understand the contemporary experience of the buildings in the mediaeval period. A good way to do this is to look at castles which fit into the background. Researching castles built for kings, dukes and archbishops can skew data towards extraordinary structures. Equally, castles built in contested borderlands can lead to a focus on military aspects which were perhaps not part of the everyday for most sites. Surveys of lordly sites in the English midlands can help to establish a framework which explains the commonplace context for most castle builders.

Subscribe to our quarterly newsletter

The Castle of Nicholas de Cantelupe

The research funded by the Castle Studies Trust at Greasley Castle (Nottinghamshire), a relatively obscure site, has afforded the rare opportunity to look at a fourteenth century baronial castle in the midlands. The castle built in the 1340s for the socially rising Nicholas de Cantelupe was probably a type instantly recognisable to many of his aspirational peers.

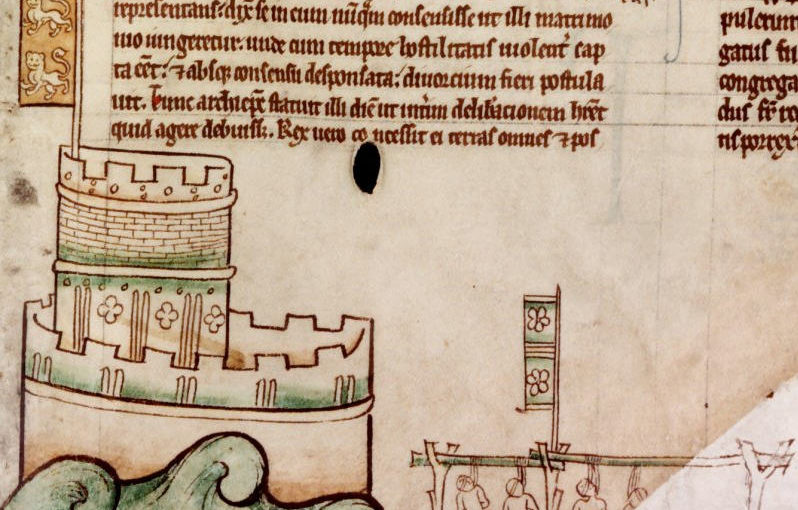

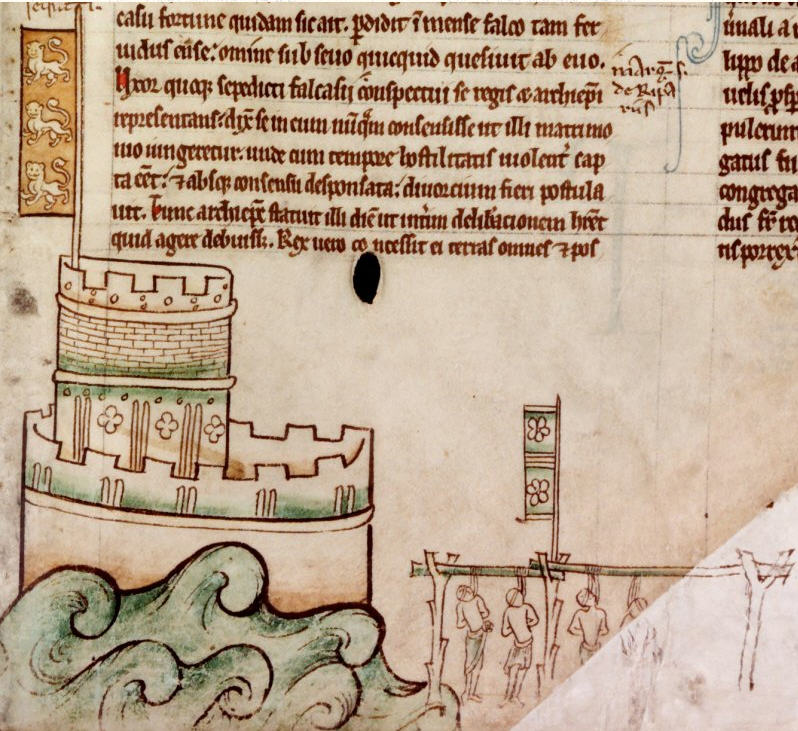

Cantelupe’s story was a familiar one. Born at the opening of the fourteenth century into a family with high-ranking connections – two of his uncles were bishops – he engaged in royal service through military campaigns in Scotland, Flanders and France. Cantelupe was then appointed Governor of the key border town of Berwick-on-Tweed, named commissioner of array in Lincolnshire and became an MP. In short, Cantelupe was exactly the sort of thrusting individual who built castles to physically cement a place in society through powerful architectural statements.

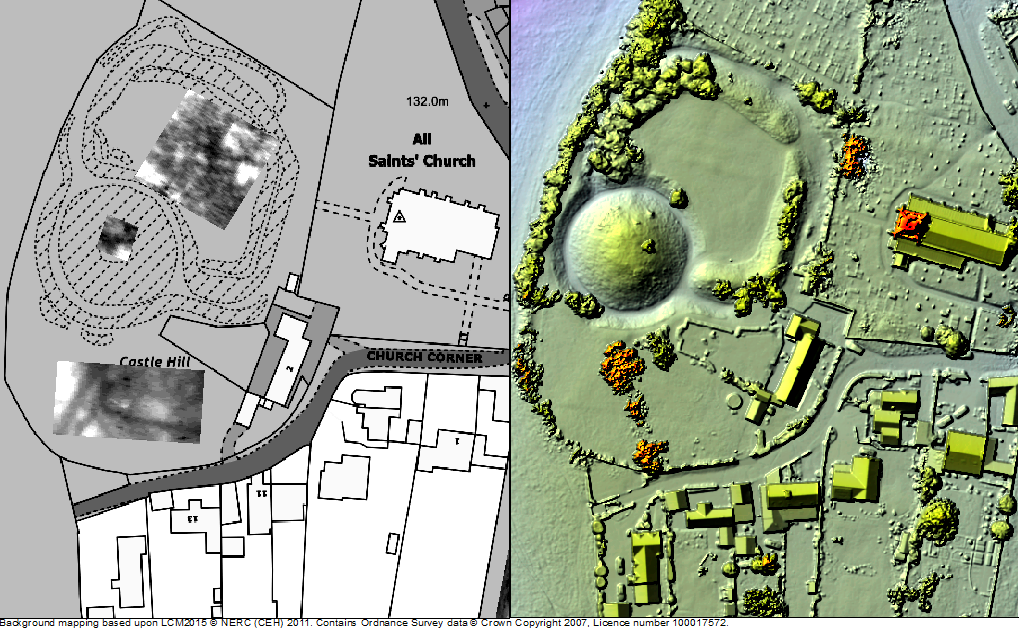

Some scholars have pointed towards Edward III’s grant of a licence to crenellate at Greasley, which Cantelupe received in 1340. However, after that note, references to the castle largely dry up. This is probably due to what the castles specialist, Oliver Creighton referred to as a “deficiency of the field evidence”. The site, a privately owned working farm, has not received much in the way of systematic survey work. Consequently, previous statements were rather scanty – it was a misunderstood castle.

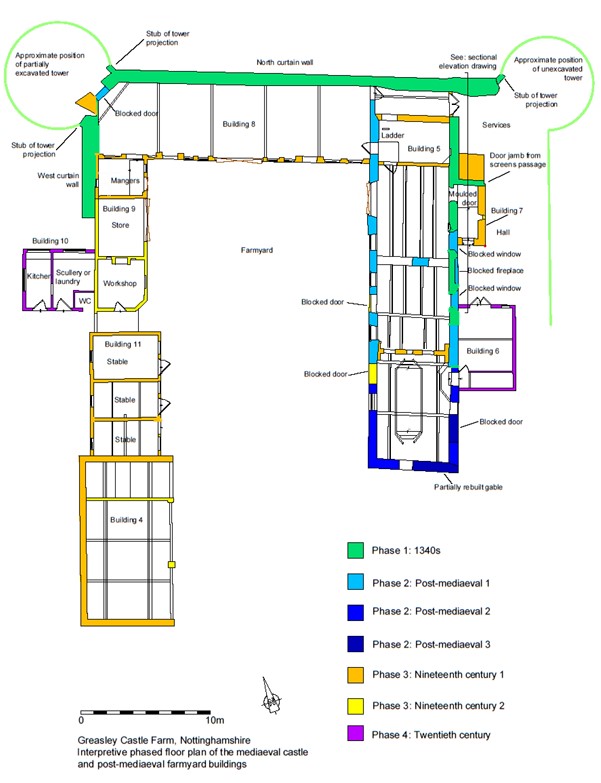

In 2021, Triskele Heritage, funded by the Castle Studies Trust, conducted a buildings archaeology survey with the intention of providing initial baseline data for the site.

Results of the Survey

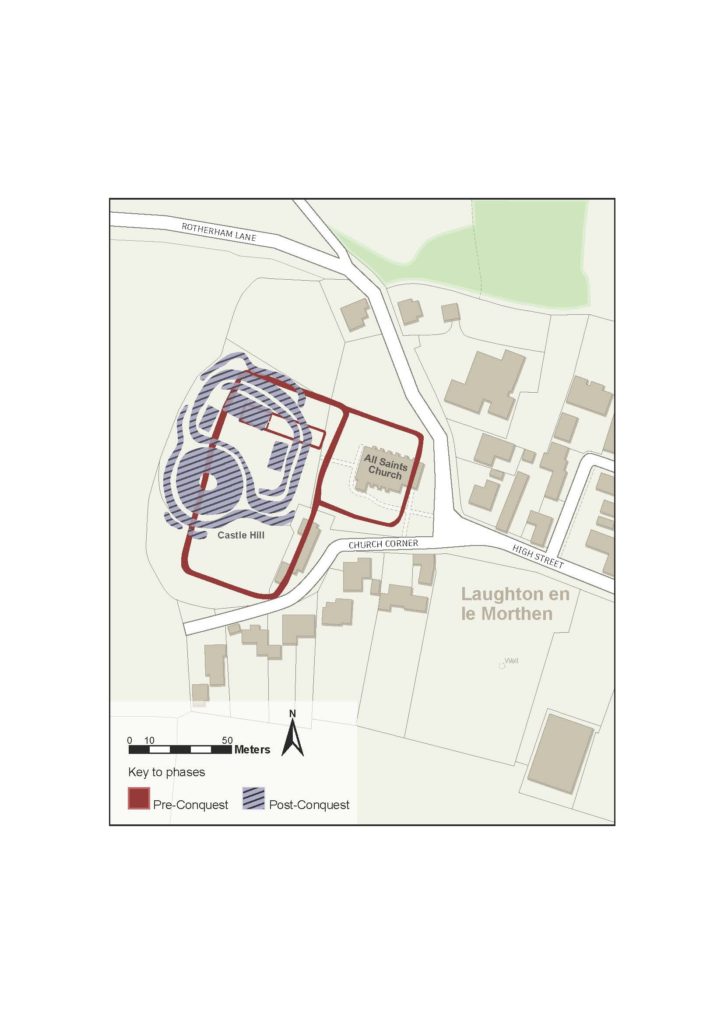

The project was able to identify that the remaining structures of the castle are located within a post-mediaeval farmyard, which lies inside a partially moated plateau. The remains of a single courtyard were identified. To the north, it is bounded by a plain curtain wall flanked bywhat were probably polygonal turrets. Part of the west curtain wall survives beneath nineteenth century farm buildings. Opposite is part of the east elevation of the great hall. Analysis revealed that a mid-fourteenth century moulded doorway allowed access into a screens passage with the hall opening to the south. Internally, this space was lit by two tall, flat headed, twin-light, double-cusped tracery windows that flanked a recessed fireplace. To the north of the hall, a stretch of ashlar wall culminates in the closer rebate of a door into a service range which probably incorporated the north-east turret.

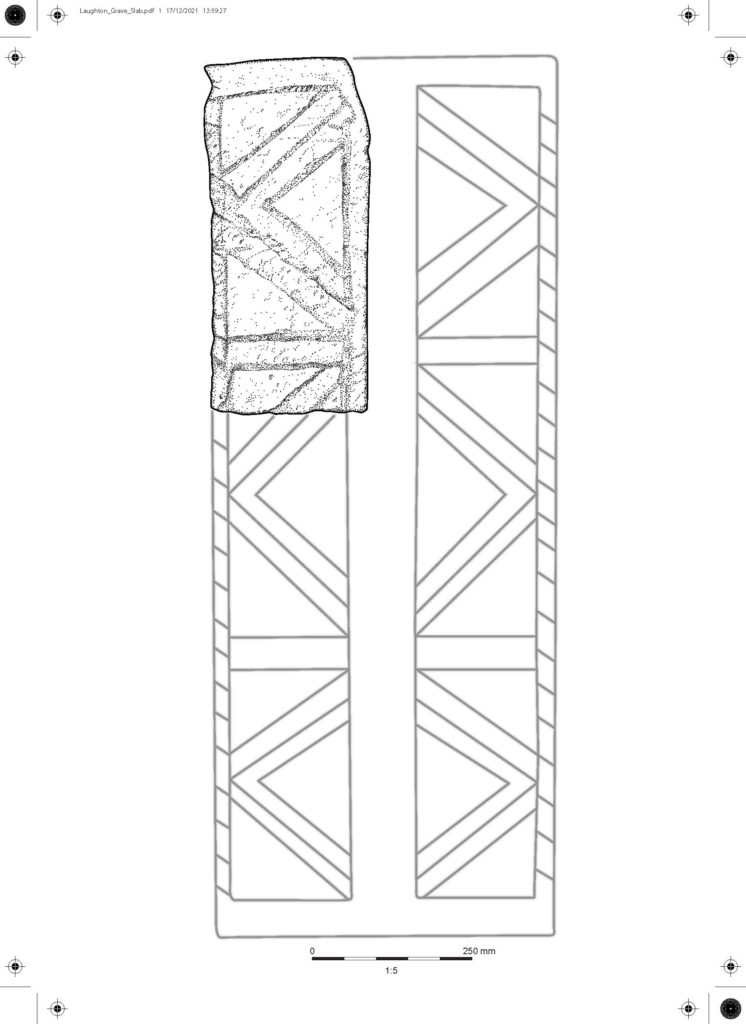

The former magnificence of Greasley can be alluded to through the identification of the substantial timbers re-used in the roof structure of a post-mediaeval barn, alongside the ex situ architectural stonework which peppers the farm structures. The latter includes carved head sculptures, tracery windows, a moulded coping, a door arch and the crown of a sexpartite vault. When considered alongside the in situ great hall door and windows, it is clear that this was once a very well-appointed castle.

Greasley in Context

With something of the plan of Greasley established, it has been possible to try and set the castle in its wider context. Cantelupe was one of several late mediaeval midlands men who sought to bolster their social position through the patronage of courtyard castles. The pattern of Cantelupe’s biography and architecture can be paralleled in the second quarter of the fourteenth century by the Vernon family at Haddon Hall (Derbyshire) and in the 1350s by Sampson de Strelley at Strelley Hall (Nottinghamshire).

Haddon is perhaps the closest parallel to Greasley in terms of landscape and architecture. Both are directly overlooked by hills to the north. The moated plateau at Greasley is 0.91 hectares in area and the double courtyard and terraced garden at Haddon are 0.76 hectares. The projected area of the great hall at Greasley (at least 57m2) is proportionate to that of Haddon (67m2) and the layout of the two – with tracery windows flanking early examples of recessed fireplaces – seems similar. Meanwhile, the probable area of the Greasley courtyard (1026m2) is comparable to Strelley Hall (1074m2). Strelley had rectangular corner turrets, whilst Greasley is likely to have had polygonal examples which can be paralleled in the mid-fourteenth century at sites including Stafford Castle and Eccleshall Castle (Staffordshire). Furthermore, the probable relationship between the services and one of the corner turrets at Greasley can be mirrored in the 1380s Drum Tower at Bodiam.

The reasons for the decline of Greasley are, like so many other late mediaeval castles, bound up with the varied fortunes of the families that owned them. For example, the ruin of nearby Strelley was brought about via a five-way division of the estate at the end of the fifteenth century which led to decades of expensive litigation, legalwrangles with neighbouring families and a catastrophic fire. Greasley was inherited by the Zouche family during the 1370s, but they eventually lost it due to the attainder of John Lord Zouche for his support of Richard III at Bosworth. There is no architectural evidence for any mediaeval construction after the original mid-fourteenth century phase and it may be that the later owners either did not remodel the castle or let it deteriorate. By the late sixteenth century the site was a roofless tenant farm.

Conclusions

Understanding the depreciation of Greasley from courtyard castle to working farm has been key to understanding this misunderstood site. By using buildings archaeology to unpick the later accretions from the surviving built environment of the castle, it has been possible for the plan form of the mediaeval architecture to be established for the first time.

Although a pale shadow of its former glory, Greasley can now be understood as a turreted courtyard castle with a fine great hall and associated services. The site was built for a socially rising aristocrat whose architectural patronage fitted well within the experience of his midland peers. It is intriguing to consider that Greasley may once have rivalled the rightly famous Haddon Hall in its heyday.

Subscribe to our quarterly newsletter

Featured Image: Buildings archaeology survey work on the exterior elevation of the great hall at Greasley Castle, Nottinghamshire (Picture Source: James Wright / Triskele Heritage)

About the author

James Wright of Triskele Heritage is an award-winning buildings archaeologist. He has a long-lived research interest in mediaeval castles, palaces and great houses. He has worked on surveys of buildings including the Tower of London, Nottingham Castle, Knole, Holme Pierrepont Hall and the Palace of Westminster. He has written books on Tattershall Castle, Kings Clipstone Palace and the castles of Nottinghamshire. James led the building survey, funded by the Castle Studies Trust, at Greasley Castle.