In its latest round of grants the Castle Studies Trust funded an ambitious 3-D reconstruction of the 12th-century form of Lincoln Castle. Project lead, Jonathan Clark, explains the background to and aims of the project.

Lincoln Castle is one of England’s great castle complexes, developed during an initial intense period of use which straddles the Conquest through to the first half of the 13th century. The reconstruction builds on the work of the recent Lincoln Castle Revealed project, which involved the conservation and repair of the castle fabric and bailey buildings, the creation of a new exhibition space, and provided a wealth of opportunities for research-led archaeology. The results of the archaeological campaign – which encountered remains from every century from the 1st to the 20th – have greatly enriched the story of the site as a whole.

Subscribe to our quarterly newsletter

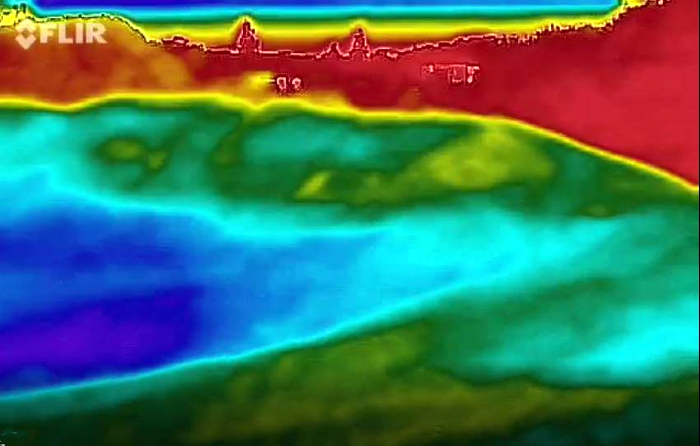

Archaeological investigations encountered elements of the Roman fortress and later Roman Upper City, the defensive enclosures of which appear to have shaped future land-use patterns well into the medieval period, including the form of the castle. The west and south Roman walls stood long into the medieval period; indeed, parts of the western defences still stand to the south of the west castle wall. The southwestern corner of the Roman fortress provided the western and southern extent of the castle bailey.

The main development of the castle in stone appears to be from the 1080s into the mid 12th century, a period which will be captured by the reconstruction. This campaign of work included the construction of East and West Gates, the stone enclosure of the bailey, the 12th-century Lucy Tower shell keep, the development of internal ranges against east and west curtain walls, adjacent to the gates, and a hitherto unknown South Gate. The South Gate position has been identified in the fabric of the south curtain wall, while its appearance has been confirmed by an early draft plan of Lincoln by John Speed, dated to 1607.

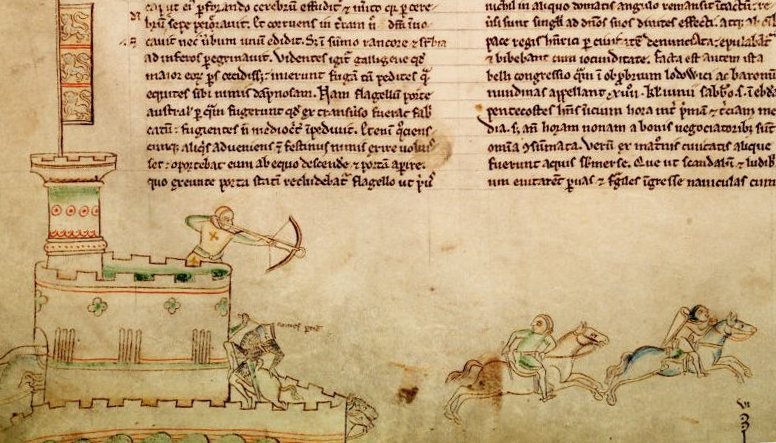

The investigations also provided valuable new information about the form and development of the main shell keep (the Lucy Tower) and the southeastern tower (known from the early 19th century onwards as the Observatory Tower). The Observatory Tower, which briefly upstaged the Lucy Tower during the Anarchy years of the early 12th century, was originally detached from the rest of the castle bailey by a substantial ditch. This ditch featured a stone revetment on the tower side which was carried up to encase the lower part of the mound on which the tower sits. The tower was subsequently remodelled to serve as gaol tower. More is now known of the Lucy Tower including the form of the roof, openings and the arrangement of rectangular chamber blocks, or turrets, to the east and west of it.

The remains of the main castle hall and various service buildings were also investigated as part of the Lincoln Castle Revealed project. Their positions are now accurately plotted within the castle bailey and these buildings are being added to the 3-D reconstruction.

A book on the archaeological discoveries from the project is forthcoming but the 3-D reconstruction will allow all to visualise an explore Lincoln Castle at its zenith. The reconstruction is being prepared by Pighill Archaeological Illustration advised by the Lincoln Castle Revealed archaeological team.

Subscribe to our quarterly newsletter

All pictures in this article are copyright of the author of the article Jonathan Clark