The striking ruins of Carreg Cennen Castle in south Wales have a rich history, bound up in power struggles between the Welsh and English and the Wars of the Roses. Dr. Dan Spencer takes us on a journey through its past.

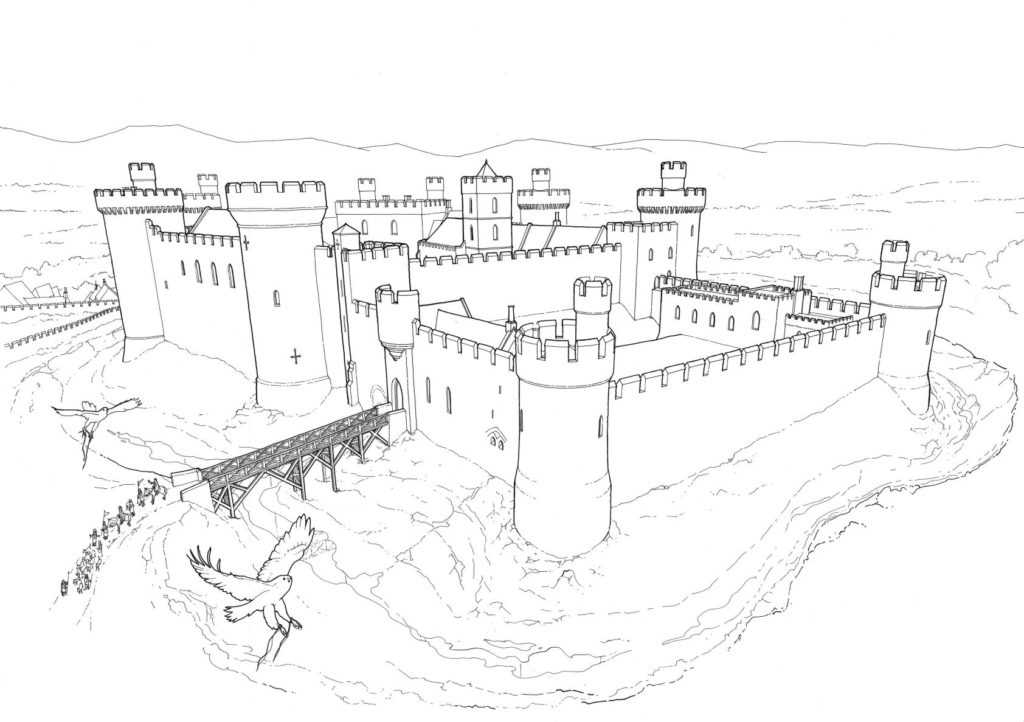

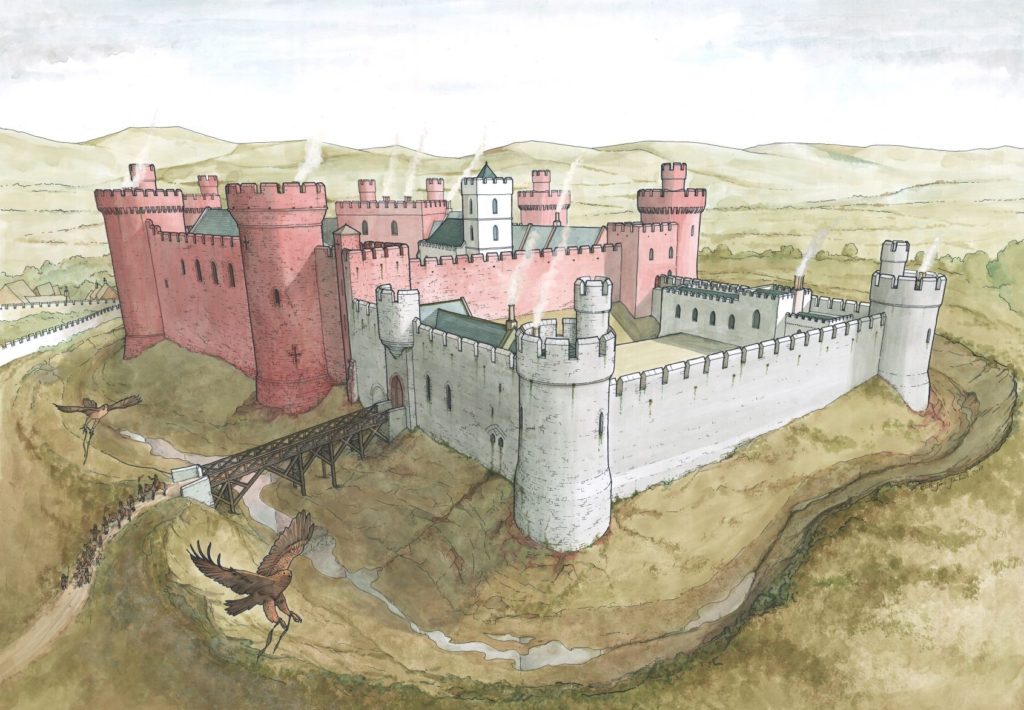

Carreg Cennen was most probably founded by the Welsh prince of Deheubarth, Rhys ap Gruffydd, in the late twelfth century. It is situated in a prominent position on a high limestone crag overlooking the River Cennen. Carreg Cennen was later captured by the English during the conquest of north Wales in the late thirteenth century. Edward I granted the castle to John Giffard, Lord Giffard of Brimpsfield, who extensively rebuilt the castle. Carreg Cennen was acquired by Henry, duke of Lancaster, in 1340, and thereafter by marriage to his son-in-law, John of Gaunt, duke of Lancaster, son of Edward III. The duchy of Lancaster subsequently passed into royal ownership, upon the accession of Henry IV, Gaunt’s eldest son, to the throne in 1399. Carreg Cennen was captured by the rebels of Owain Glyn Dŵr in the early fifteenth century, with repairs carried out during the reign of Henry V.1

In 1455, Welsh landowner Gruffydd ap Nicolas seized the castle, taking advantage of a power vacuum in south Wales, where many of the principal royal offices were held by absentee officials. This move was not welcomed by the government of Henry VI. Gruffydd subsequently came into conflict with Edmund Tudor, earl of Richmond, a half-brother of the king, in the following year. Richmond eventually emerged victorious from the struggle in the late summer of 1456, at which time it appears that Gruffydd relinquished control of Carreg Cennen.2 The earl died of the plague later that year, with the task of maintaining royal authority in southern Wales thereafter entrusted to his brother, Jasper Tudor, earl of Pembroke.

In 1459, civil war broke out when the Yorkist lords, Richard, duke of York, Richard Neville, earl of Salisbury, and his son Richard Neville, earl of Warwick, attempted to seize power. This development prompted Jasper to install a garrison in the castle, which remained in place until at least the following year.3 It is not known how large the garrison was, and Carreg Cennen appears not to have seen any military action at this time. This is not surprising, as potential attackers would have been deterred by its strong defences. It was also in a relatively isolated location, far removed from the main areas of conflict.

Instead the fate of Carreg Cennen was decided by events elsewhere. The decisive clash of the conflict took place at the Battle of the Towton on 29 March 1461, the largest engagement of the Wars of the Roses. The Yorkists led by Edward IV were victorious, with Henry VI and his remaining supporters forced to take refuge in Scotland. Later that summer, Edward delegated the task of subduing Wales to some of his trusted supporters, who included William, Lord Herbert.4

By the end of 1461, the Yorkist commanders had succeeded in conquering almost all of Wales (with the main exception of Harlech in the north-west), and Jasper Tudor fled overseas. This left Carreg Cennen as the last remaining Lancastrian fortress in the south. In the spring of 1462, Lord Herbert instructed his half-brother, Sir Richard Herbert, and another member of the gentry, Sir Roger Vaughan, to take control of the castle. They set off from Raglan Castle, Herbert’s ancestral seat, with a force of 200 gentlemen and yeomen and soon reached Carreg Cennen. The defence of the latter was led by Thomas and Owen ap Gruffydd, sons of the recently deceased Gruffydd ap Nicolas. It is unclear whether they had been given this responsibility by Jasper Tudor, or if they had exploited the situation to take control of the castle. Either way, the brothers were said to have a large force under their command and had a strong defensive position. Nevertheless, the futility of the Lancastrian cause prompted them to surrender under terms. They were pardoned in return for pledging allegiance to Edward IV.5

On Lord Herbert’s instructions, the castle was provisioned, and a garrison was installed for its safeguard. This consisted of a small force of nine men, who served there from the beginning of May until mid-August. These men each received 4d. per day in wages, the standard rate for footmen or archers at this time, as well as 1s. 10d each per week to pay for their expenses.6 The garrison was required, as is explained in a surviving letter from Edward IV, because ‘the said castle was of such strength that all the misgoverned men of that country there intended to have inhabited the same castle and to have lived by robbery and spoiling our people of the country’. However, as the letter went on to explain ‘we soon after were advised that the said castle should be thrown down and destroyed’ to avoid the inconvenience of expending money on maintaining its defence. The source of this advice is unspecified, but it could have been from Lord Herbert, who, as chamberlain of south Wales, was acutely aware of the financial burden of paying for its garrison. This was an extraordinary decision, as no other castle was slighted by royal command at this time, which may have reflected Yorkist concerns about its potential as a formidable fortress in an area with Lancastrian sympathies. It could also have stemmed from more general unease about law and order in the region. The king therefore issued orders to Herbert to oversee its destruction. A labour force of 500 men was recruited who used a variety of tools to ‘break and throw down’ the castle.7 The extent of the destruction is unclear, but at the very least the labourers made the place uninhabitable, with Carreg Cennen thereafter falling into ruin.

Subscribe to our quarterly newsletter

Dr. Dan Spencer is the author of The Castle in the Wars of the Roses, published by Pen & Sword, which is due for release on 30 October: https://www.pen-and-sword.co.uk/The-Castle-in-the-Wars-of-the-Roses-Hardback/p/18426

Footnotes

[1] J. M. Lewis, Carreg Cennen (Cardiff: Cadw, 2016), p 1; H. M. Colvin, The History of the King’s Works, volume 2 (London: H.M.S.O, 1963), p. 602.

[2] For Gruffydd’s seizure of the castle and conflict with Edmund Tudor see, William Rees, ed., Calendar of Ancient Petitions relating to Wales (Cardiff: University of Wales Press, 1975), pp. 184-6; PL, I, pp. 392-3.

[3] For the garrisoning of Carreg Cennen by Jasper see, TNA, DL 29/584/9249; DL 29/596/9558.

[4] For an overview of these events see, Anthony Goodman, The Wars of the Roses (London: Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1991).

[5]. For the occupation of the castle by the sons of Gruffydd ap Nicolas and its surrender see, TNA, SC 6/1224/6; SC 6/1224/7.

[6] TNA, SC 6/1224/6.

[7] Quoted from TNA, SC 6/1224/7, whose Middle English text has been modernised.

![[10] Druminnor Castle - "Woops!"](https://farm6.staticflickr.com/5125/5340893447_176baa5abf_b.jpg)