With the excavation report on the third and final season of excavation which the CST has funded now published on our website, project lead Dr Nigel Baker looks at what has been achieved since the first work in 2019 to now.

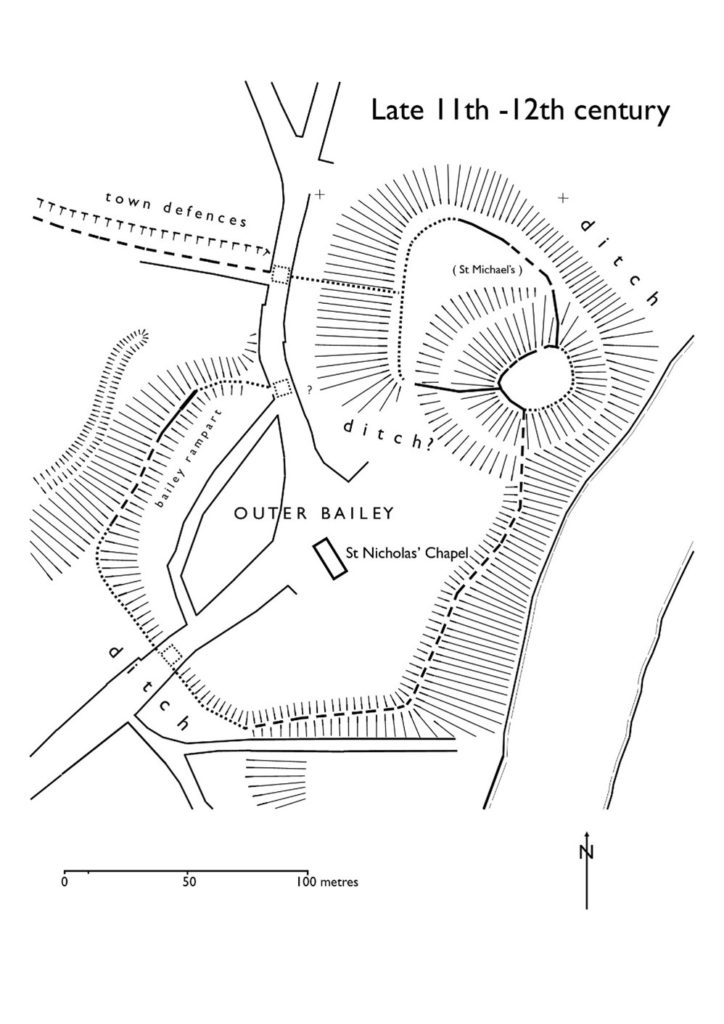

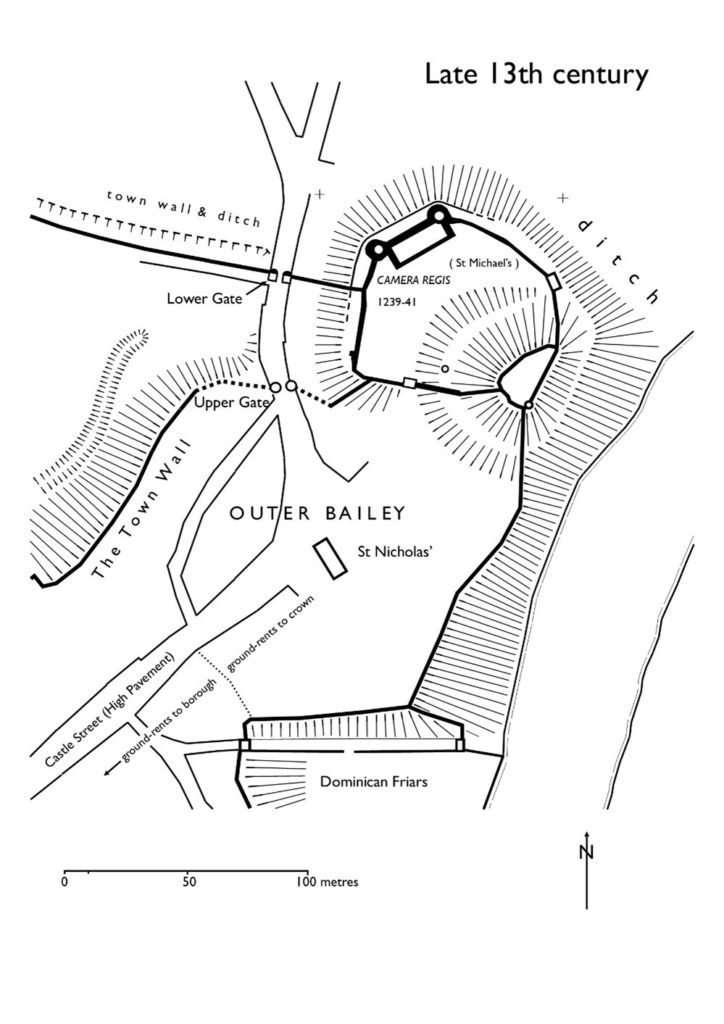

Just over a century ago Shrewsbury Castle began a new phase in its long life. In 1925 its principal surviving building, having been in use as a private dwelling since the castle was finally de-munitioned in 1686, became the meeting hall of Shrewsbury Borough Council, set in extensive landscaped gardens covering the remains of the motte and inner bailey, the outer bailey having (mostly) disappeared beneath the growing town by c.1300. Shrewsbury Castle remained more or less untouched by archaeology for the remainder of the 20th century. This changed in 2019 with the award by the Castle Studies Trust of a grant for a season of geophysical survey and excavation in the inner bailey. Following permission from Shropshire Council, the site owners, and Historic England, its legal guardians, the work took place in May and July 2019, the geophysics by contractors Tiger Geo and the excavation team made up of experienced local volunteers and staff and students of University Centre Shrewsbury. The results were unexpected.

Subscribe to our quarterly newsletter

Immediately under the turf was natural glacial gravel: the top of the hill on which the castle had been built; the ground surface had been lowered sometime in the past, removing nearly all archaeological remains. This was almost certainly the work of the young Thomas Telford who, from 1786 to 1790, lived in and ‘restored’ the castle for its owner, Sir William Pulteney, M.P. for Shrewsbury. However, archaeological strata were found to have survived within cuts into the natural gravel, and two of these were of major significance. The first was the edge of a previously-unknown ditch around the base of the motte. Medieval cooking-pot sherds of late 11th-13th-century date were found in its lowest excavated layers, along with two armour-piercing crossbow quarrel heads. The second significant find was of a pit containing in its fill a piece of decorated bone and two types of pre-Conquest (Saxon) pottery: Stafford-type ware, distributed widely across the emerging towns of the region and already well represented in Shrewsbury; and a limestone-tempered fabric, TF41a, never before seen in Shrewsbury, which had been made in the Gloucester area and probably imported up the Severn. This confirms that there was pre-Conquest activity on the site of the castle, and, along with the Domesday evidence that there was a church of St Michael there by 1086, may point in the direction of a high-status pre-Norman presence on this tactically-significant site controlling access to the ancient borough.

Excavation resumed in the autumn of 2020 with a trench seeking a sample profile through the west rampart of the inner bailey. This turned out not to be medieval in date. Both the west and the north rampart were probably created as part of Thomas Telford’s landscaping work in 1786-90. But, intriguingly, below the west rampart there was no sign within the trench of the natural hilltop gravel found close by in 2019 at a depth of just a few centimetres. The explanation may be that the bailey was enlarged westwards between the Norman period and the later medieval period, by dumping soil and levelling-up behind a new curtain wall.

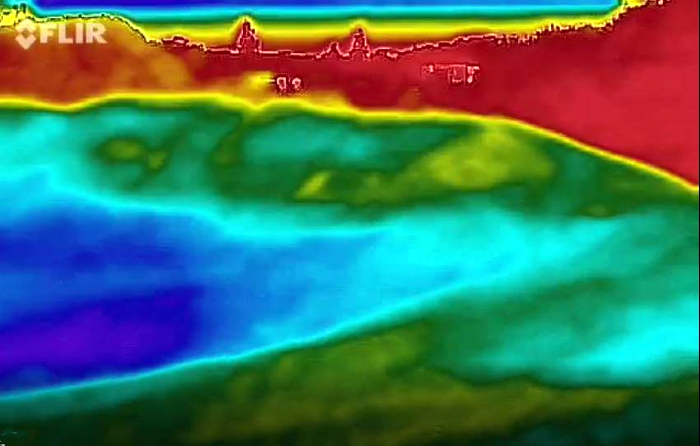

The final season of excavations took place in 2022 on the top of the motte, and outside the north curtain wall. Telford is known to have demolished ruined medieval buildings on the top of the motte and replaced them with the surviving two-storey Gothic summerhouse there. Excavation showed that Telford’s activities had, again, removed most of the archaeology but that the foundations of early medieval timber buildings (beam slots, a post pad, post holes) survived where they had been cut into the motte material. No definite trace was seen of the ‘great wooden tower’ which is documented on the motte top until its collapse in 1269-71.

New light was also shed on the motte by vegetation clearance on its south side, revealing for the first time remains of buildings incorporated in the masonry of the retaining walls. This work was undertaken on behalf of Shropshire Council for a new conservation-management plan, currently at consultation stage, which includes photogrammetric surveying of all the castle structures. This permanent stone-by-stone record not only forms the basis for the next vital stage of work – identifying and specifying long-needed repairs – it also offers new archaeological insights, including the identification of the probable primary sandstone rubble fabric of the curtain walls. This was in turn followed by some research carried out by Jason Hurst on Civil War musketry damage in 2023 (Potential shot damage at Shrewsbury Castle – Castle Studies Trust Blog) . And now, the process of publishing this body of new archaeological, architectural and historical information is just beginning…