Back in 2015 the Castle Studies Trust co-funded the post excavation & publication of Steven Bassett’s excavations 1972-1981 of Pleshey Castle in Essex. In the November 2018 issue of Current Archaeology (334) Patrick Allen explains how the review of the excavation materials has transformed our understanding of the castle and provided new insights into its character and development.

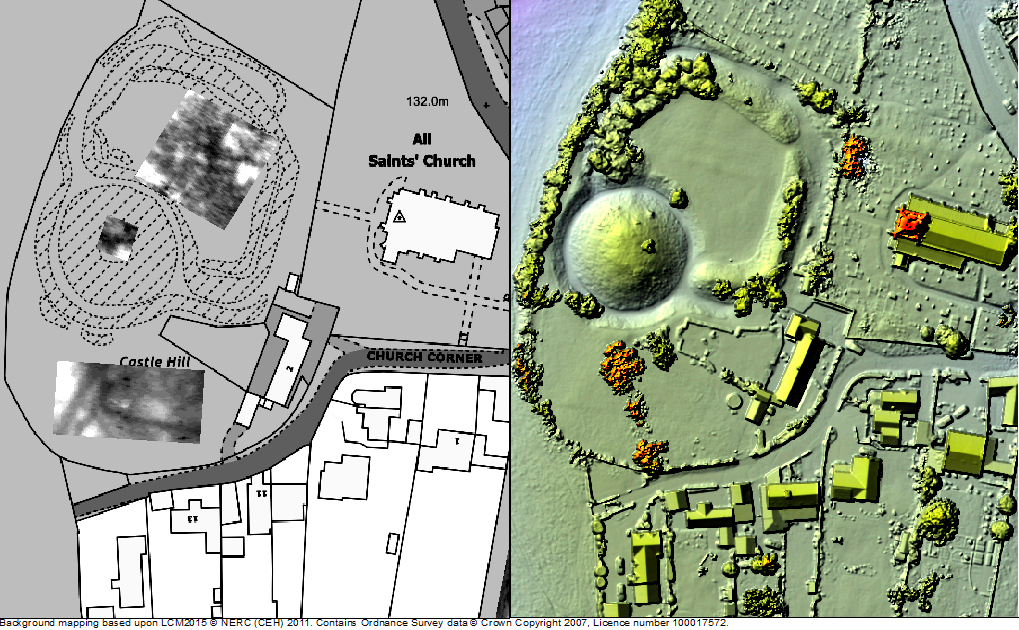

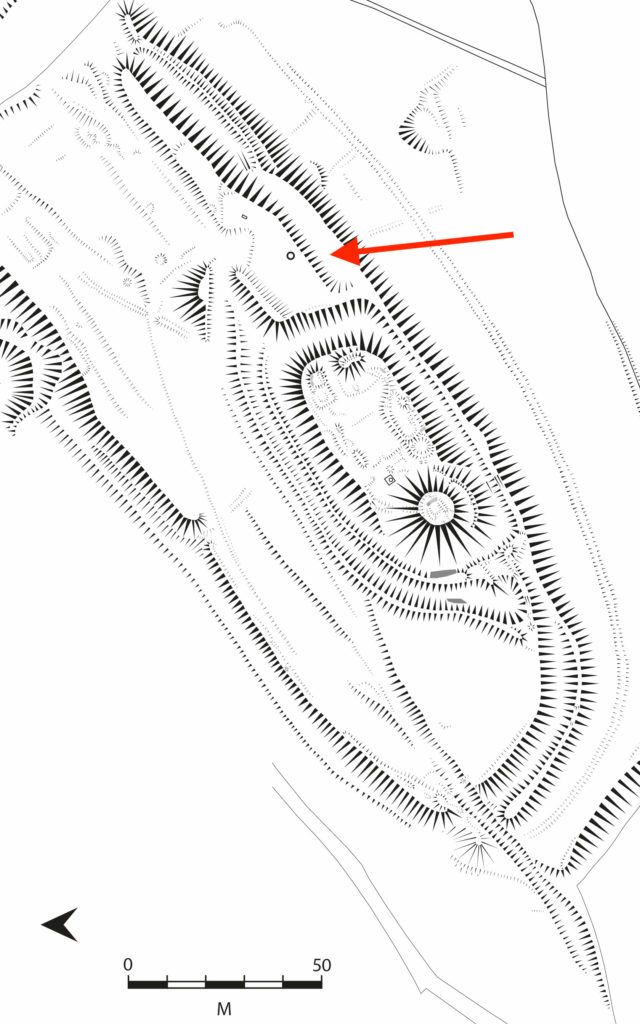

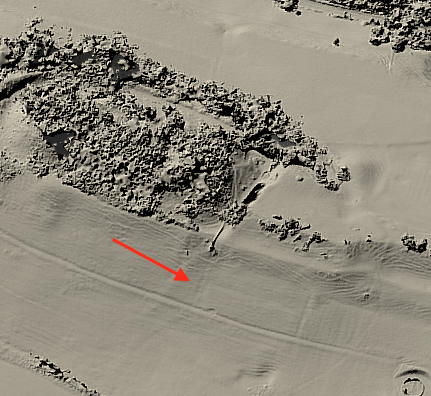

Around 5 miles northwest of Chelmsford in Essex we find a classic example of a motte and bailey fortification. Pleshey Castle offers invaluable insights into constructions of this kind, as while all of its buildings have long been demolished (apart from the late 15th-century brick bridge over the motte moat), its medieval earthworks have survived intact thanks to their never having been rebuilt in stone.

Subscribe to our quarterly newsletter

Its motte is original, dating from c.1100, while the ramparts of the south bailey are largely the result of refortification which took place in 1167. A second bailey to the north of the motte is now buried beneath the modern village, but its original outline can still be seen in Pleshey’s semi-circular street plan and in 1988 was confirmed by excavation. Its defences were levelled in the 13th century and replaced by a much larger town enclosure, whose earthworks still surround the modern village.

Previous descriptions of the castle had assumed that the north bailey was part of the original castle and the south bailey added later – but recent reassessment of all available evidence has transformed this picture completely.

Evolving the castle

What can we unpick about the castle’s origins? Its earliest documentary reference comes from 1143, when Geoffrey II de Mandeville surrendered all his lands, including Pleshey Castle, to King Stephen. Yet scientific research suggests the site is much older. Analysis of topsoil buried beneath the motte, and a calculation of the rate of its formation, suggests that the castle was completed 30-40 years after the Norman Conquest.

As for when construction began, tree-ring dating of a timber from the north bailey palisade provides a date no earlier than 1083, and a construction date of c.1100 seems entirely plausible. This would link the castle’s creation not to Geoffrey II de Mandeville, but to Geoffrey I – a logical conclusion as the core of his extensive estates lay in mid-Essex and Pleshey is close to his chief manor of Waltham (now Great Waltham).

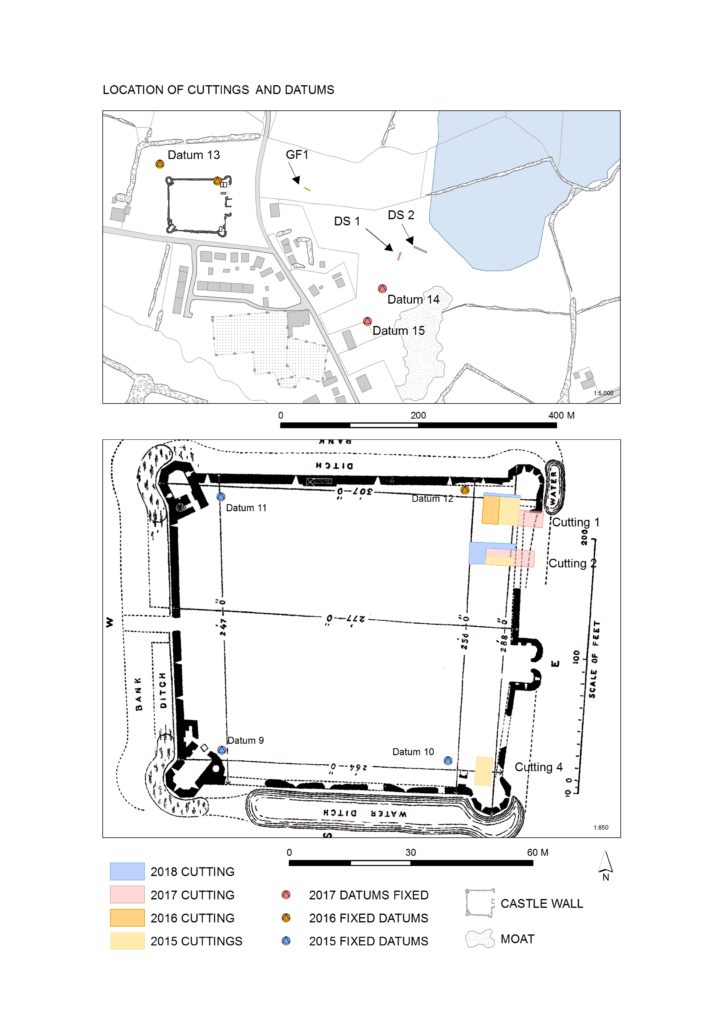

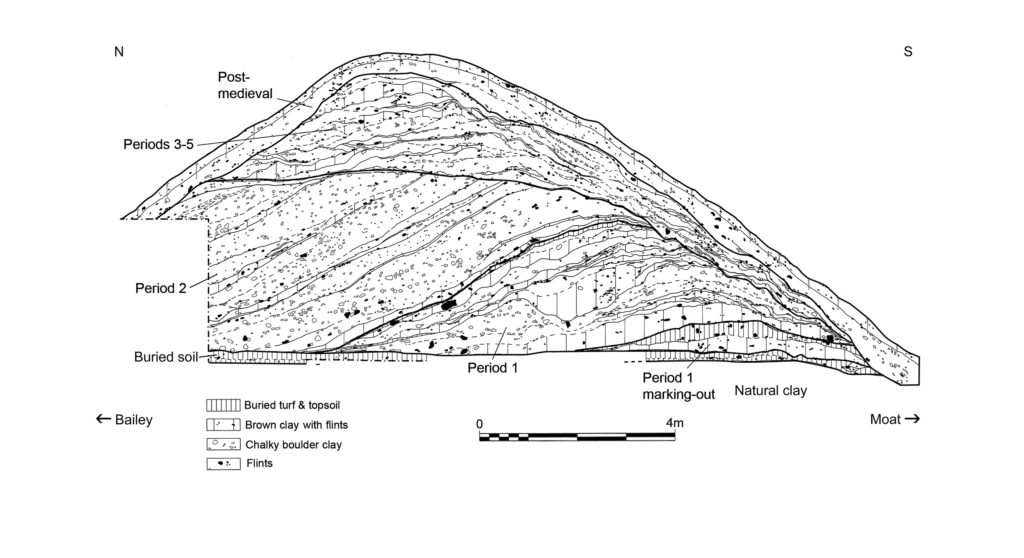

It is also becoming increasingly clear how the fortifications developed; Chelmsford Museums Service has been revisiting unpublished reports from an excavation that Steven Bassett undertook immediately to the south-east of the brick bridge in 1972-1981. Interestingly, a section that he recorded through the outer rampart confirms that the south bailey was also part of the original construction of the castle – that is, Pleshey boasted two baileys from its inception. Within this rampart (which was dated to the later 12th century by previous excavations headed by Philip Rahtz in 1959-1963), Bassett also found traces of a smaller, earlier rampart which had been built up in two stages, suggesting an initial temporary earthwork which was completed after a short interval.

As for later developments, historical accounts record that in 1157-1158 Henry II returned the de Mandeville lands to Geoffrey III on the condition that he dismantled the defences of his castles – but in 1167, Geoffrey’s younger brother William II de Mandeville was given permission to refortify. There is good archaeological evidence for a large-scale restoration of the castle defences after this date, following the same plan as before. Bassett’s excavation uncovered clear signs of a comprehensive clearing out of the moat during this period, and sections recorded by both Bassett and Rahtz (in an early dig) show the south bailey rampart being massively enlarged at the same time.

This, though, was the last major improvement to the castle defences. Its earth and timber fortifications provided sufficient protection against local insurrection, but the castle was not defensible against a major attack, and during the civil war that followed King John’s rejection of Magna Carta it changed hands twice. On Christmas Eve 1215 Pleshey Castle was seized by a detachment of the king’s army, and in the winter of 1216-1217 it was recaptured by the rebel barons – both times it was surrendered without a siege. The castle was militarily outdated, and after it was inherited by the powerful de Bohun family in 1227/1228 it became increasingly important not as a fortification but as their main residence and the administrative centre of a great aristocratic estate.

Subscribe to our quarterly newsletter

Bridges and bailey buildings

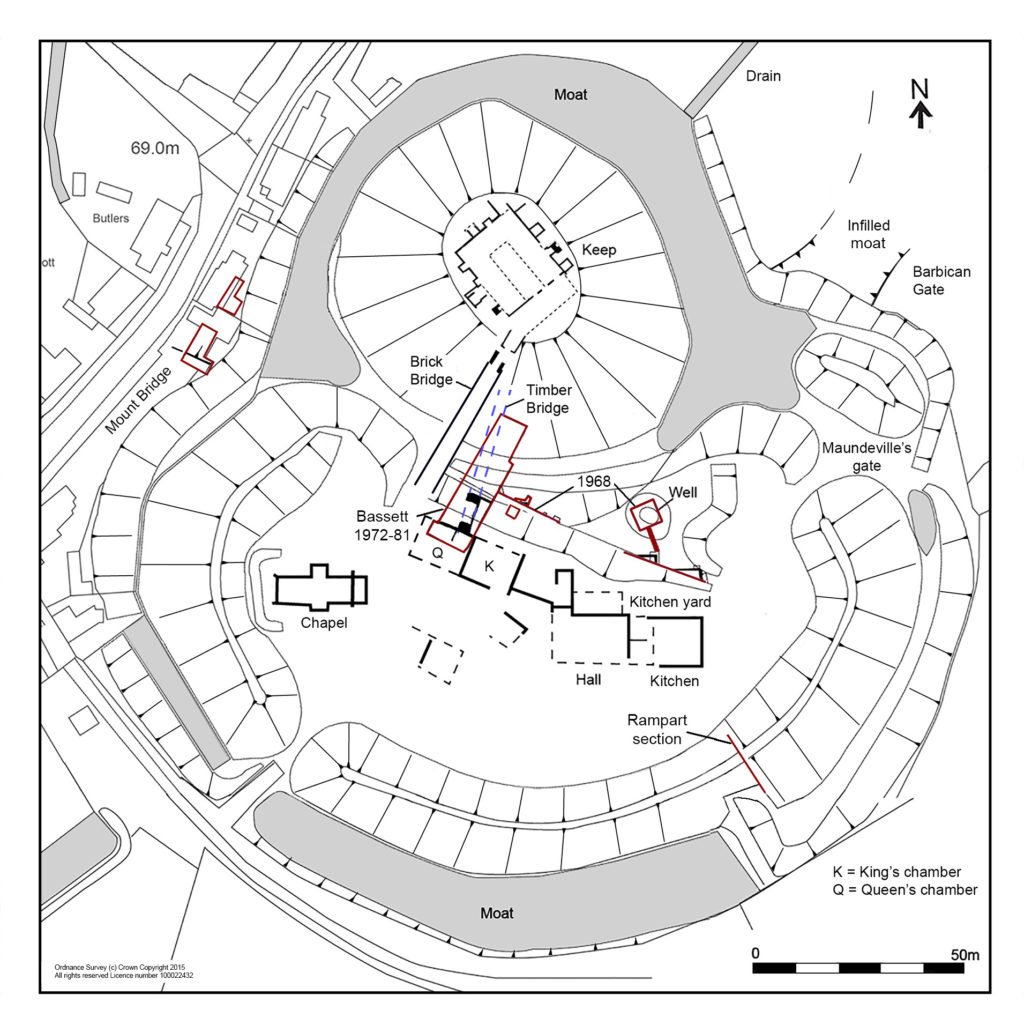

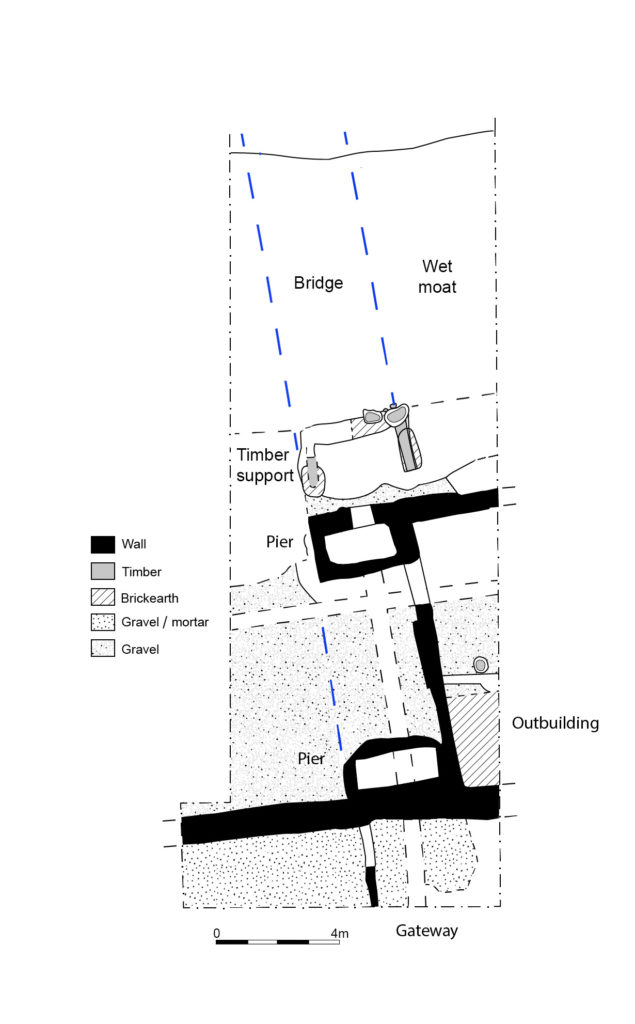

Between Pleshey’s refortification in 1167 and the late 14th/early 15th century four successive wooden bridges spanned the motte moat. Traces of these trestle structures were recorded by Bassett as well as in a small trench excavated by Elizabeth and John Sellers. The final development of the south end of the bridge consisted of two stone pier bases which would have supported box-frame timber uprights and, in front of these, a wooden structure supporting massive raked timbers which carried the central span of the bridge over the wet part of the moat.

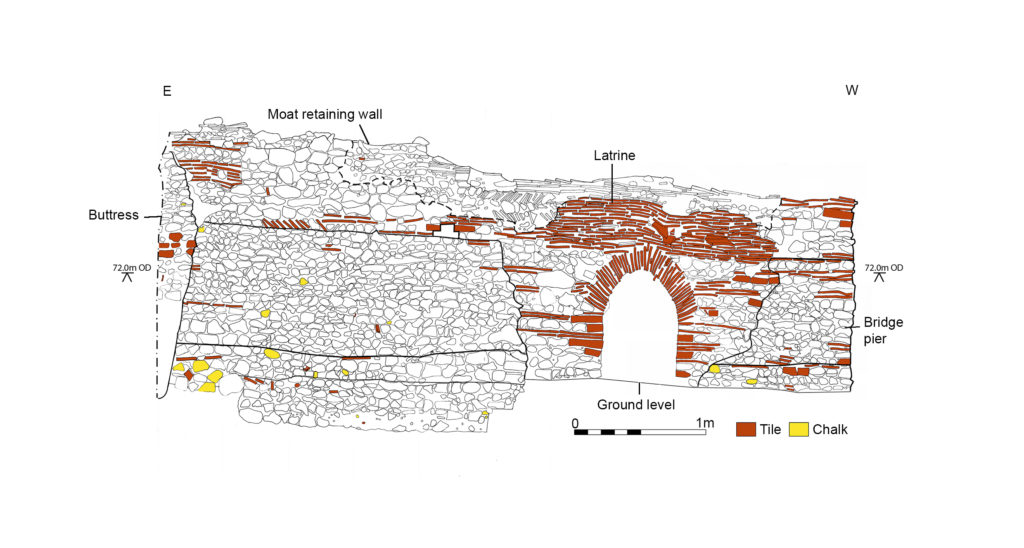

These strong foundations were needed at the bailey end of the bridge to support the greater load there from the bridge’s superstructure, whose walkway would have sloped steeply from the motte down to the bailey. Meanwhile, the elevation of the outer face of the northern bridge pier shows its solid construction and its continuation to the east to form a retaining wall for the moat. This pier was later reworked to create a latrine in the late 15th century – when the wooden bridge was replaced by a brick one – evidence of this change still survives in the form of an inserted arch and changes to the upper stonework.

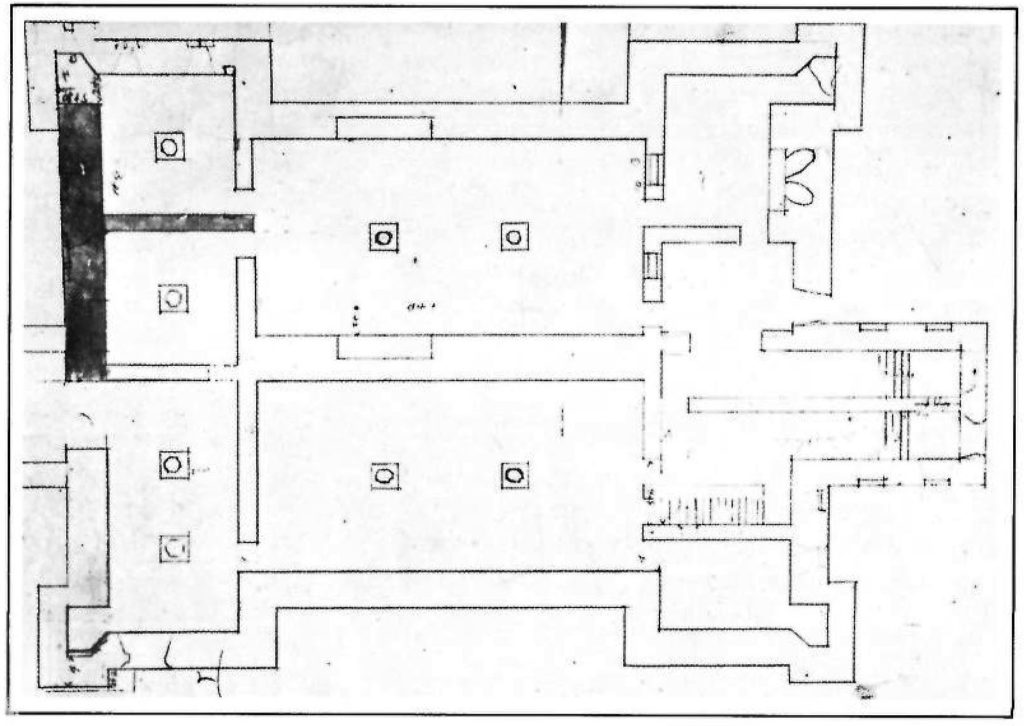

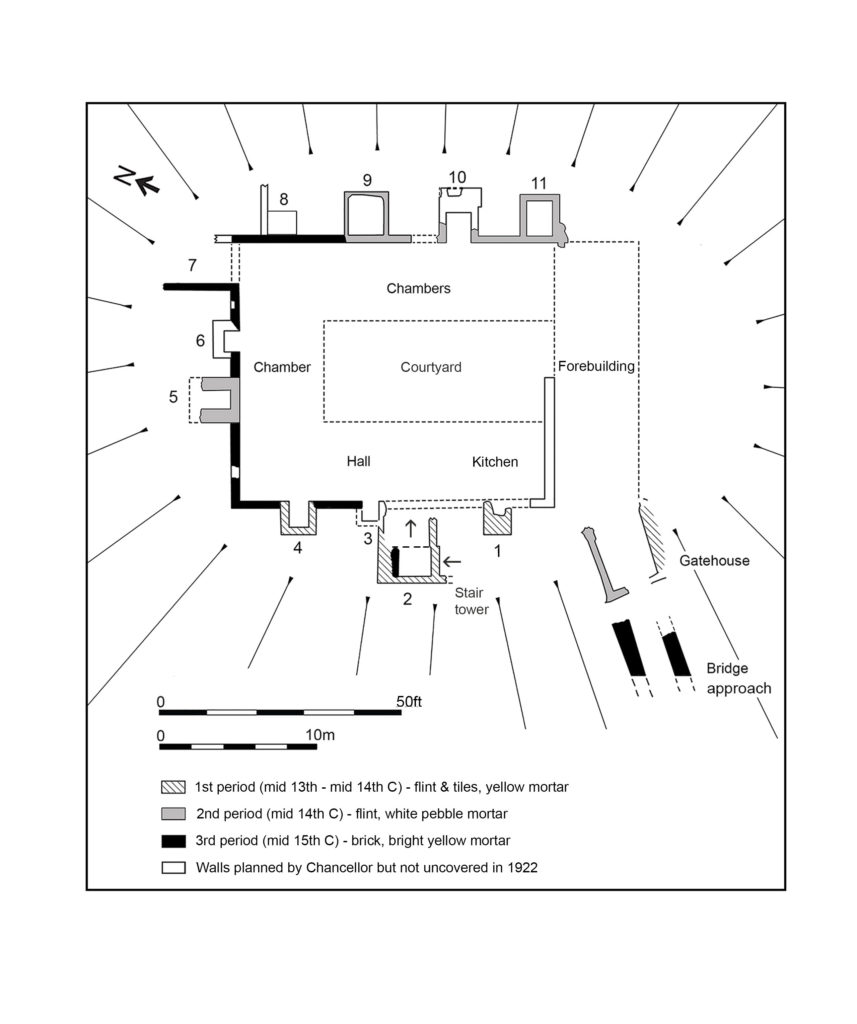

What of other structures? As mentioned before, all of the castle’s buildings have long been demolished, but it is possible to piece together some clues. A plan of the buildings that were present in the south bailey from the 14th century onwards can be reconstructed using evidence from Bassett’s excavations and a 1960s parchmark survey by Elizabeth and John Sellers. Furthermore, the function of some specific buildings can be identified thanks to Pat Ryan’s study of the surviving mid-15th-century Duchy of Lancaster building accounts for the castle.

We are able to locate the chapel at the west end of the bailey, which was excavated by Rahtz in 1959-1963. To the east, the hall is easily identifiable, with its adjoining kitchen, pantry, and buttery. On its north side, storehouses were ranged around a kitchen yard which was accessible from the main gate immediately to the east. To the west of the hall was a range of large private chambers at first-floor level, above a wardrobe and other storerooms. These were a ‘revealing chamber’ (audience chamber), and at the west end of the range lay the ‘King’s chamber’ and, beyond it, the ‘Queen’s chamber’. This relates to the period 1421-1483 when Pleshey became part of the Duchy of Lancaster, the private estate of the Lancastrian kings, and was granted to three successive Queens of England: Catherine of Valois, Margaret of Anjou, and Elizabeth Woodville, the wives of Henry V, Henry VI, and Edward IV respectively.

Bassett’s excavations also recorded part of a stone-built gatehouse at the south end of the bridge, whose upper chamber can be identified as the Queen’s chamber in the building accounts. The gateway and the room to its west, possibly a guard chamber, were surfaced in gravel and mortar, but material found in the demolition rubble indicates that the Queen’s chamber above was much grander, with a floor of Penn-type decorated tiles, painted plastered walls, and leaded glazed windows.

Bassett’s investigations date the completion of the building range along the north side of the bailey to the late 14th century. These buildings would have been constructed by the de Bohuns and completed by Thomas of Woodstock, Duke of Gloucester (the youngest son of Edward III), who married Eleanor, the elder de Bohun heiress. It is she, as Duchess of Gloucester, who would have originally occupied the Queen’s chamber in its initial guise.

Exploring the keep

Our project also reassessed the results of the excavations focusing on the castle keep in 1907 and 1921-1922. There, the original excavators were puzzled by the ‘extreme thinness of the walls’, but we suggest that they should be interpreted as facades built around a timber-framed courtyard structure. The keep’s great hall has been located using its description in the building accounts, while the other ranges are thought to represent chambers with ‘ensuite’ accommodation, each with a fireplace and a privy (which survive as rectangular projections that are open to the interior, and enclosed, respectively).

The final renovation of the keep – carried out on the orders of Margaret of Anjou and described in detail in the building accounts for 1458-1459, where the keep is referred to as a ‘tower’ – was finished in brick. The accounts also record that 29 oaks were felled for the work and that most of the money was spent on employing carpenters – confirmation that the keep was mainly built in timber, as suggested above. Two earlier periods of flint facades and additional structures are dated to the mid-13th/mid-14th century and the late 14th century respectively (by comparison of mortar types with well-dated structures recorded in Bassett’s excavations). No doubt the stone and brick facades made an essentially timber structure look more impressive.

The renovation of the keep was completed by building the brick bridge over the moat, probably in 1477-1480, according to Pat Ryan’s study of the building accounts. This was 20 years after the work on the keep itself – perhaps the works were delayed by the Wars of the Roses (1455-1487). The brick bridge is one of the earliest of its type in Europe and, with its wide span, was a very advanced design for its time. By the mid-16th century, though, the castle had become derelict, with the motte mound used as a rabbit warren, and it was sold by Elizabeth I in 1559. Ironically, the brick bridge was preserved only because the Duchy of Lancaster surveyors recommended that it be retained to maintain access to the warren. Today, it still stands as one of the few elements of the castle surviving above ground. Analysis of excavated evidence has enabled us to add much more colour to this picture, and to reconstruct Pleshey Castle’s appearance once more.

Subscribe to our quarterly newsletter

The author would like to thank the following for grants towards the project: the Castle Studies Trust, the Marc Fitch Fund, the Essex Heritage Trust, and the Essex Society for Archaeology and History.

Featured image: Aerial view of Pleshey courtesy of Chelmsford Museums Service