Dr Lorna-Jane Richardson, University of East Anglia/Bungay Museum, looks at the 1930s excavations of Bungay carried out by Hugh Braun and also the possibility of future work at the site.

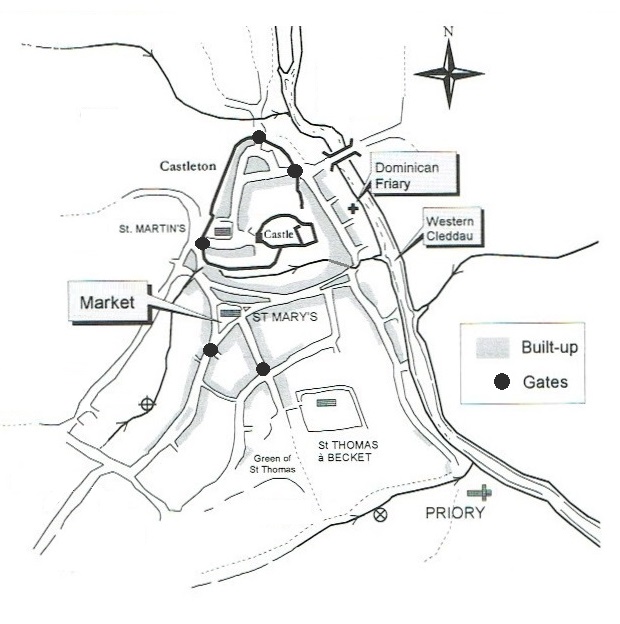

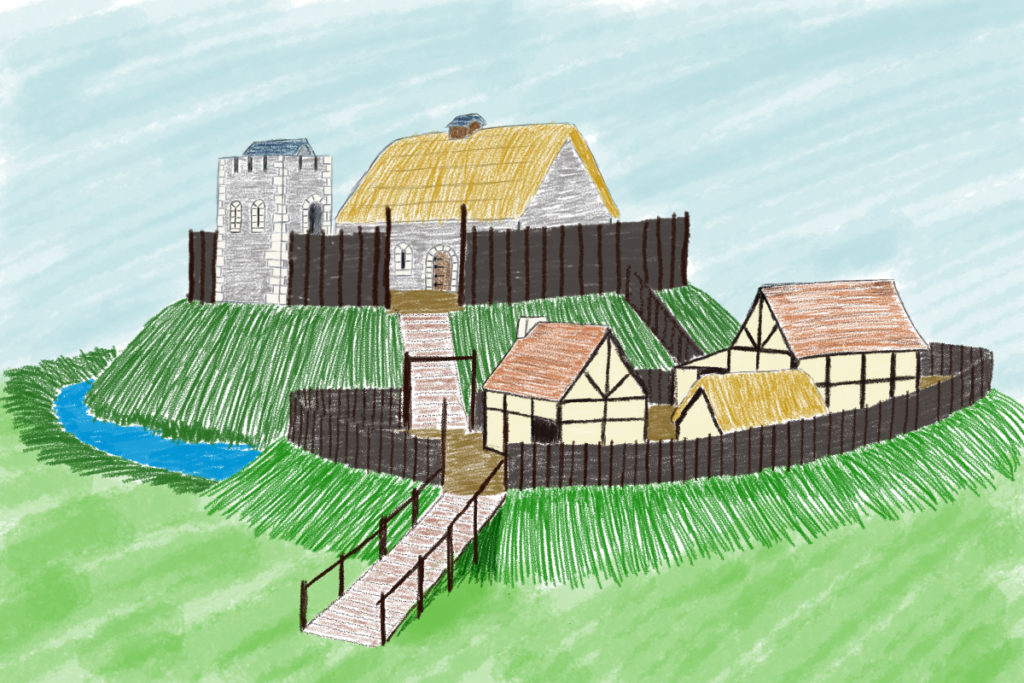

Bungay is a small market town on the border of Norfolk and Suffolk, and sits on a meander in the River Waveney at the very edge of the Norfolk Broads National Park. The town is in a good defensive position, sat on a sand and gravel river terrace, some 10 metres above OD, with wide views across the valley and surrounded by marshland. This ‘natural fortress’ (Braun 1934) had seen earlier, perhaps early Medieval, defensive structures built, suggestive of a burh. This site was chosen for the construction of a castle firstly by one of William the Conqueror’s stewards, William de Noyers, who constructed a motte and bailey structure. The castle was bestowed on Roger Bigod, a Norman knight who was awarded estates in East Anglia and given Bungay in 1103 by King Henry I. Roger’s son, Hugh, known as Bigod the Restless, was made Earl of Norfolk in 1154, and he ordered the construction of the stone keep. The Bigods were the most powerful family in East Anglia for much of the 12th and 13th centuries. After nearly two centuries in the hands of the Bigod family, who also owned Framlingham Castle further south in Suffolk, Bungay Castle reverted to the Crown and fell into disuse. In 1312, Edward II gave the Castle to his brother, Thomas Plantagenet, and it eventually passed to the Dukes of Norfolk in 1483. However, it was recorded as being ‘ruinous’ by 1362, and over the subsequent centuries, the site was used as a source for building materials, the gatehouse was converted into a residence for an eighteenth-century novelist, and the keep was also used as a beer garden by the King’s Head Inn at least until the early 1930s.

A group of Bungay dignitaries, led by the Town Reeve and local doctor Leonard Cane, leased the site from the Duke of Norfolk, and on 19th November 1934, the excavation of the site commenced. This excavation took place under the leadership of Dr Cane and Hugh Braun, an architect from London who had worked in Iraq with the Chicago University Expedition at the site of Nineveh. The excavation provided work for unemployed war veterans and interestingly, engaged the services of a local water diviner, one Mr John Davey who can be seen in Fig 2, to locate water and gold during the excavations. Further research is underway in an attempt to discover more about these veterans, and the role played by Mr Davey and his water-magic.

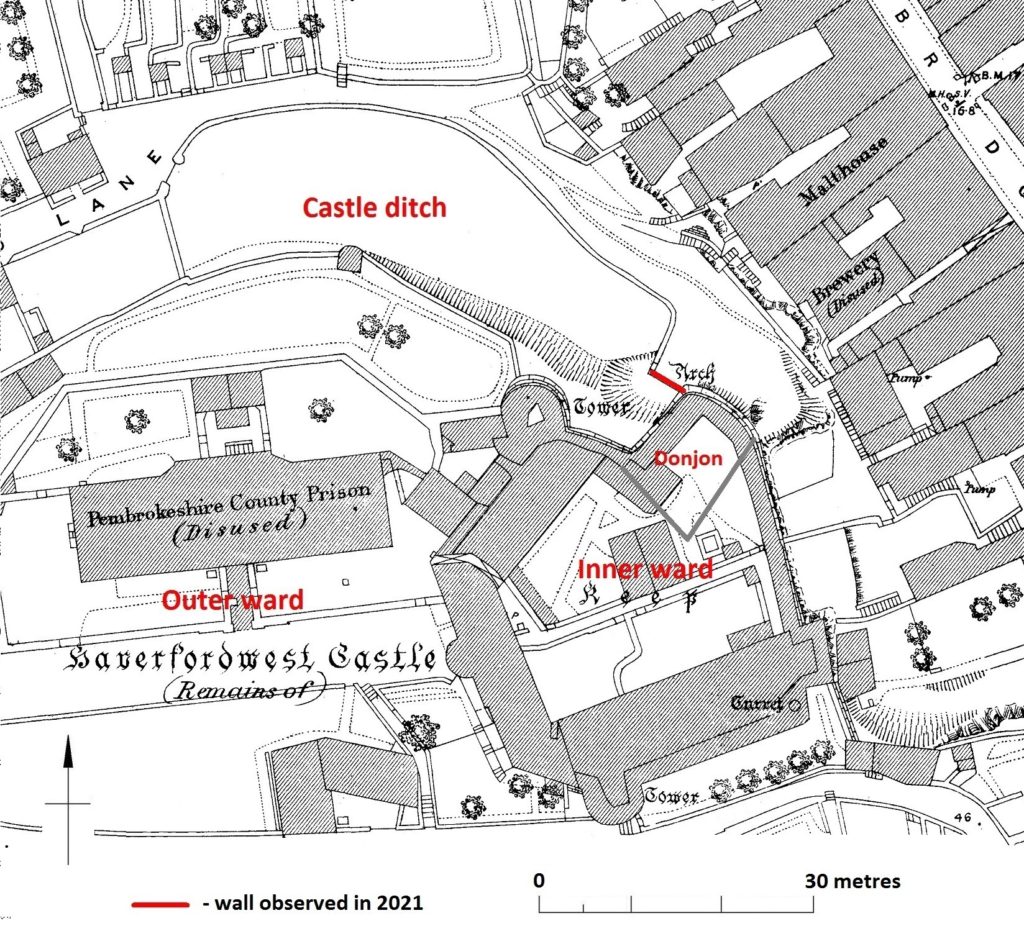

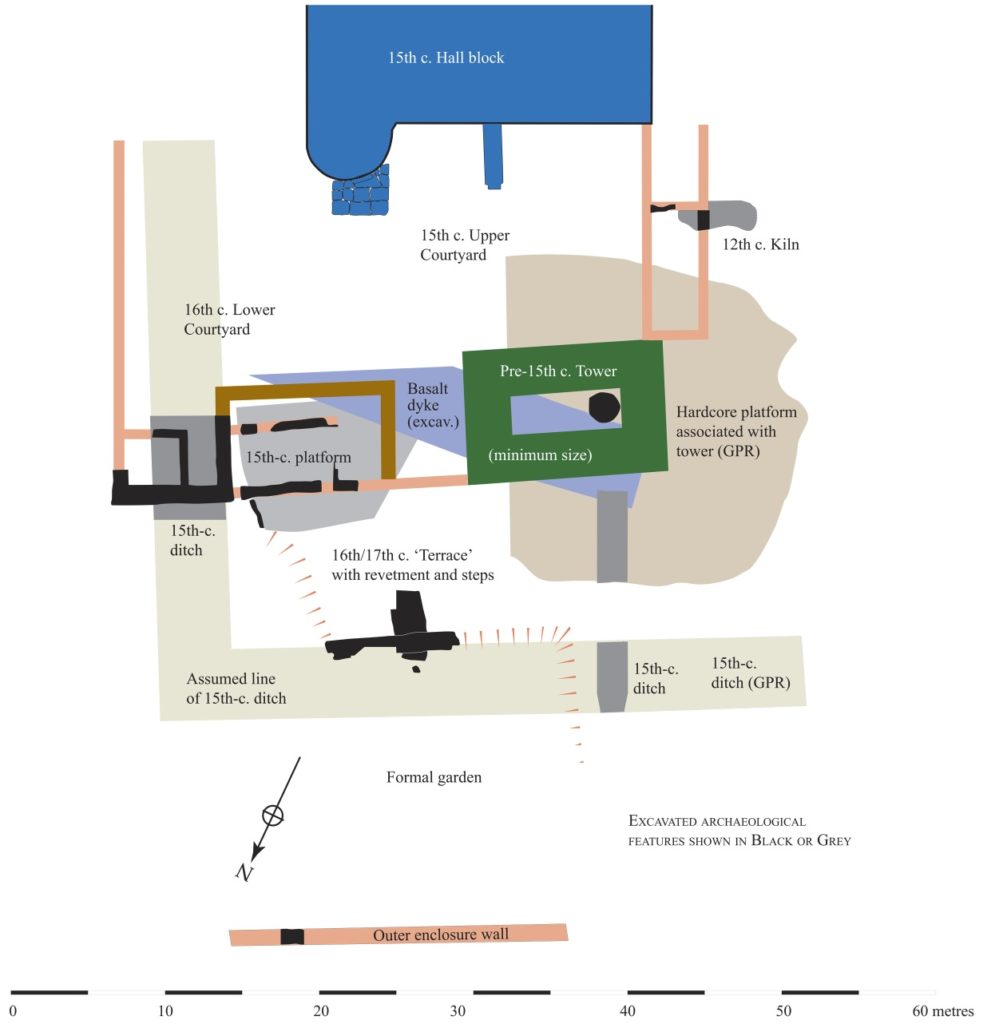

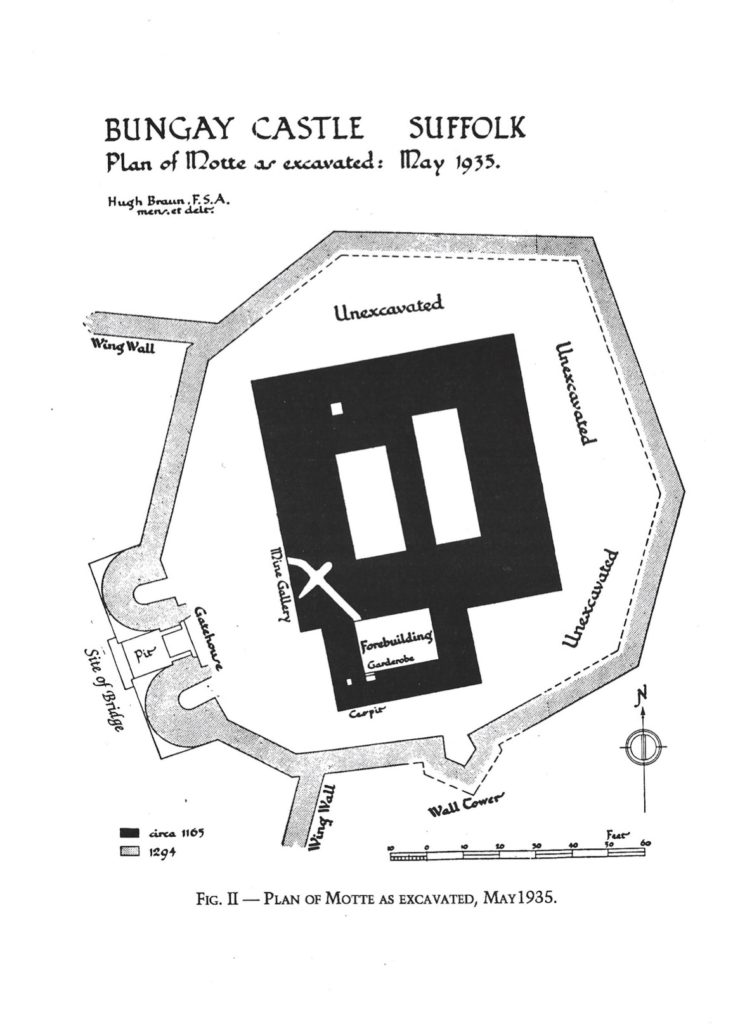

The excavations initially concentrated on the area between the keep ruins and the gatehouse, and around the keep itself, revealing buried walls which “would show the castle rising some twenty feet higher than before the excavation commenced” (Braun 1991, 23). The drawbridge pit was excavated, and the west wall of the keep was exposed, but other areas of the gatehouse and keep were left intact, after the excavation ran out of funds. Some of these areas were, according to Braun’s report, tidied and returfed ready for further exploration at a later date. These areas remain untouched, and no further excavations in the area of the gatehouse or keep have taken place since 1934. The excavations were subsequently published in the Proceedings of the Suffolk Institute of Archaeology and History in 1934, 1935 and 1936. There have been no further major archaeological excavations, although some unpublished monitoring work took place in 2001, 2006 and 2008 according to the HER, and geophysical work took place at the Castle in 1990 (Gaffney & Gater) and 2017 (Schofield). In 2017, what is now Cotswold Archaeology Suffolk undertook a detailed geophysical survey of the area of the inner bailey, which demonstrated very high potential for archaeological material and structural remains. These include evidence for buildings, a potential well, and a variety of pits some of which feature ferrous debris. Bungay Castle holds much potential for further archaeological work.

These photographs are from the Braun/ Cane excavations at Bungay Castle and are dated to 1935. They are part of the Bungay Museum collection, and there are around 40 images which feature the excavations, the people involved, and a variety local dignitaries and visitors to the site. In January 2021, I became curator of Bungay Museum, which was originally established in 1968 by Dr Leonard Cane’s son, Dr Hugh Cane. As part of this role, I plan to undertake further research into the contents of the museum collection, local contemporary news articles about the excavations, as well as Ministry of Works documents held at Kew, in order to develop new displays about the site and Bungay’s very own version of ‘The Dig’. Basil Brown himself would have certainly visited the excavations, as he lists the site in his notebooks, and he lived relatively locally. I hope my research will reveal more information about the names and lives of the veterans who dug the site, how the excavation was managed and run, more about the archaeological finds, and the mysterious role of water divination in the process. There are many interesting stories waiting to be told about the original excavations at Bungay Castle, and many more are waiting in the wealth of archaeology that remains in the ground.

Subscribe to our quarterly newsletter

Feature image: Bungay Castle copyright Andrew Atterwill

References

Braun, H. (1934). “Some notes on Bungay Castle”. Proceedings of the Suffolk Institute of Archaeology and Natural History XXII.1, pp. 109–119.

— (1935). “Bungay Castle, report on the excavations”. Proceedings of the Suffolk Institute of Archaeology and Natural History XXII.2, pp. 201–223.

Braun, H. and G. Dunning (1936). “Bungay Castle: Notes on 1936 excavations and on pot- tery from the mortar layer”. Proceedings of the Suffolk Institute of Archaeology and Natural History XXII.3, pp. 334–338.

Gaffney, C., and Gater, J. (1990). Report on Geophysical Survey, Bungay Castle. Geophysical Surveys Bradford, Report 90/60.

Schofield, T. (2017) Bungay Castle, Bungay, Suffolk BUN 004 Geophysical Survey Report. Suffolk Archaeology Community Interest Company Report No. 2017/078.