The deadline for grant applications passed on 1 December. We’re going through the various projects now. Altogether the 14 projects, coming from all parts of Britain, one from Ireland, are asking for £88,000. They cover not only a wide period of history but also a wide range of topics.

We will not be able to fund as many of these projects as we would like. To help us fund as many of these projects as possible please donate here: https://donate.kindlink.com/castle-studies-trust/2245

In a little more detail here are the applications we’ve received:

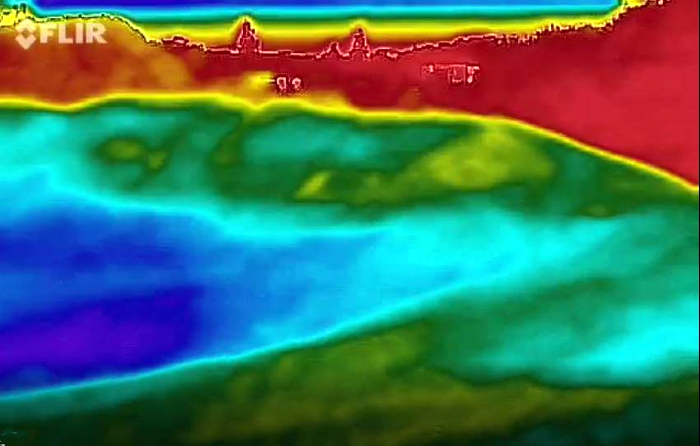

Caerlaverock, Dumfriesshire: The aim is to understand the chronology and geography of extreme weather events in the high medieval period, and the effects they wrought on archaeological features that led to the abandonment of the old castle in favour of the new.

Georgian Castles: This project explores two castles in County Durham—Brancepeth and Raby—that were fundamentally reshaped and transformed in the eighteenth century to become notable homes in the area, and it advances not only our understanding of these two buildings in the period, but also the afterlife the castles in the area and the layers of history that they record.

Greasley, Nottinghamshire: The production of an interpretative phased floor plan for Greasley Castle in Nottinghamshire. The castle, built in the 1340s, has an obscure history and the understanding of its architectural phasing is at best very cloudy.

Laughton-en-le-Morthen, South Yorkshire: To provide professional illustration and reconstruction which will also be integrated into the co-authored academic article. Part of the monies will be used to produce phase plans of Laughton during key stages of its development, and a small percentage will pay for a line drawing of the grave cover.

Lost medieval landscapes, Ireland: To develop a low cost method, using drone and geophysical survey to identify native Irish (also termed Gaelic Irish) medieval landscapes and deserted settlements.

Mold, Flintshire, post excavation analysis: Post-excavation analysis from excavation on Bailey Hill of the castle

Mold, Flintshire, digital reconstruction: Visual CGI reconstruction of Mold Castle using the new-found evidence of further masonry on the inner bailey structure and using information gathered by the Bailey Hill Research Volunteers, showcasing the many changes that have happened on this site from a Motte and Bailey Castle to present time as a public park.

Old Wick, Caithness: Dendrochronological assessment of timber at the Castle of Old Wick, Caithness thought to be one of the earliest stone castles in Scotland.

Orford, Suffolk: recording the graffiti at the castle through a detailed photographic and RTI (Reflectance Transformation Imaging) survey will add to our understanding of how the building was constructed and the ways the building was used over time, particularly 1336-1805, during which the documentary history of the castle provides little evidence of how the site developed.

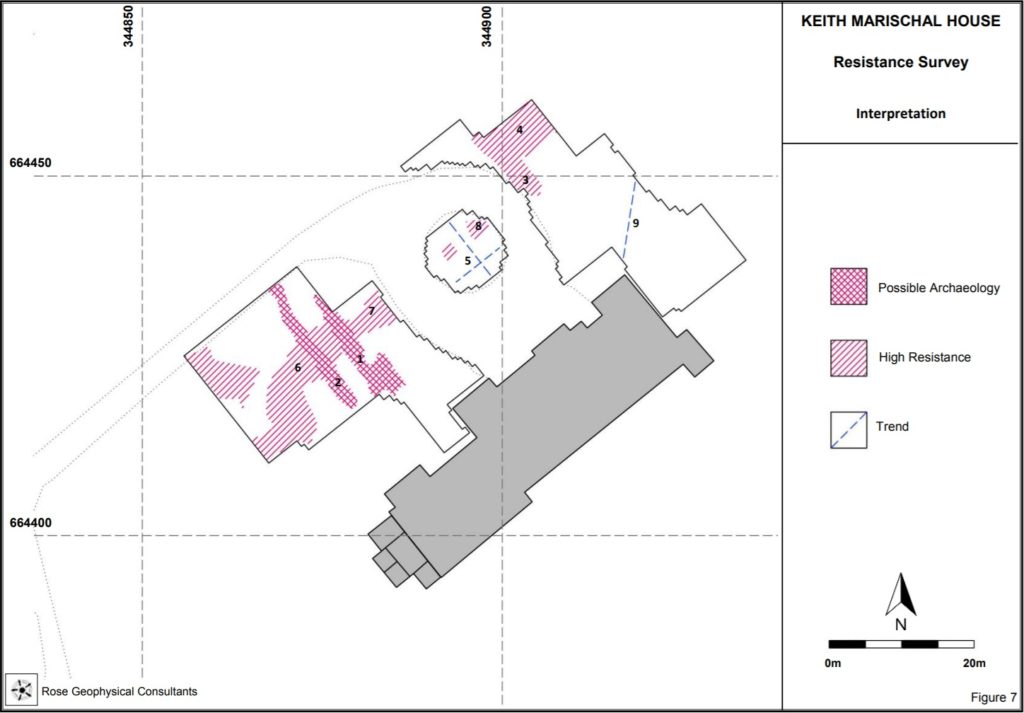

Pembroke, Pembrokeshire: A second season of trial-trench evaluation of the suggested late-medieval, double-winged hall-house in the outer ward at Pembroke Castle, which is of national significance. The evaluation builds on the results of the works undertaken through previous CST grants: geophysical survey (2016) and 2018 whereby two trenches were excavated across the possible mansion site. The evaluation will again establish the extent of stratified archaeological deposits that remain within the building, which was excavated during the 1930s.

Pevensey, East Sussex: GPR survey of the outer bailey and immediate extramural area and UAV (aerial) survey of the castle to build up a 3-D model of the site.

Richmond, North Yorkshire: Co-funding a 3 week excavation of Richmond Castle, one of the best preserved and least understood Norman castles in the UK. The aim is to understand better the remains of building and structures along the western side of the bailey.

Shootinglee Bastle, Peeblesshire: Funding post-excavation work from the 2019-20 excavation season in particular some charcoal deposits from a C16 burning event.

Warkworth, Northumberland: Geophysical survey to explore evidence for subsurface features in and around the field called St John’s Close in a field adjacent to the castle.

We will not be able to fund as many of these projects as we would like. To help us fund as many of these projects as possible please donate here: https://donate.kindlink.com/castle-studies-trust/2245

The applications have been sent to our assessors who will go over them and prepare their feedback for the Trustee’s who will meet in late January to decide on which grants to award.

![[10] Druminnor Castle - "Woops!"](https://farm6.staticflickr.com/5125/5340893447_176baa5abf_b.jpg)